The Alien and Sedition Acts

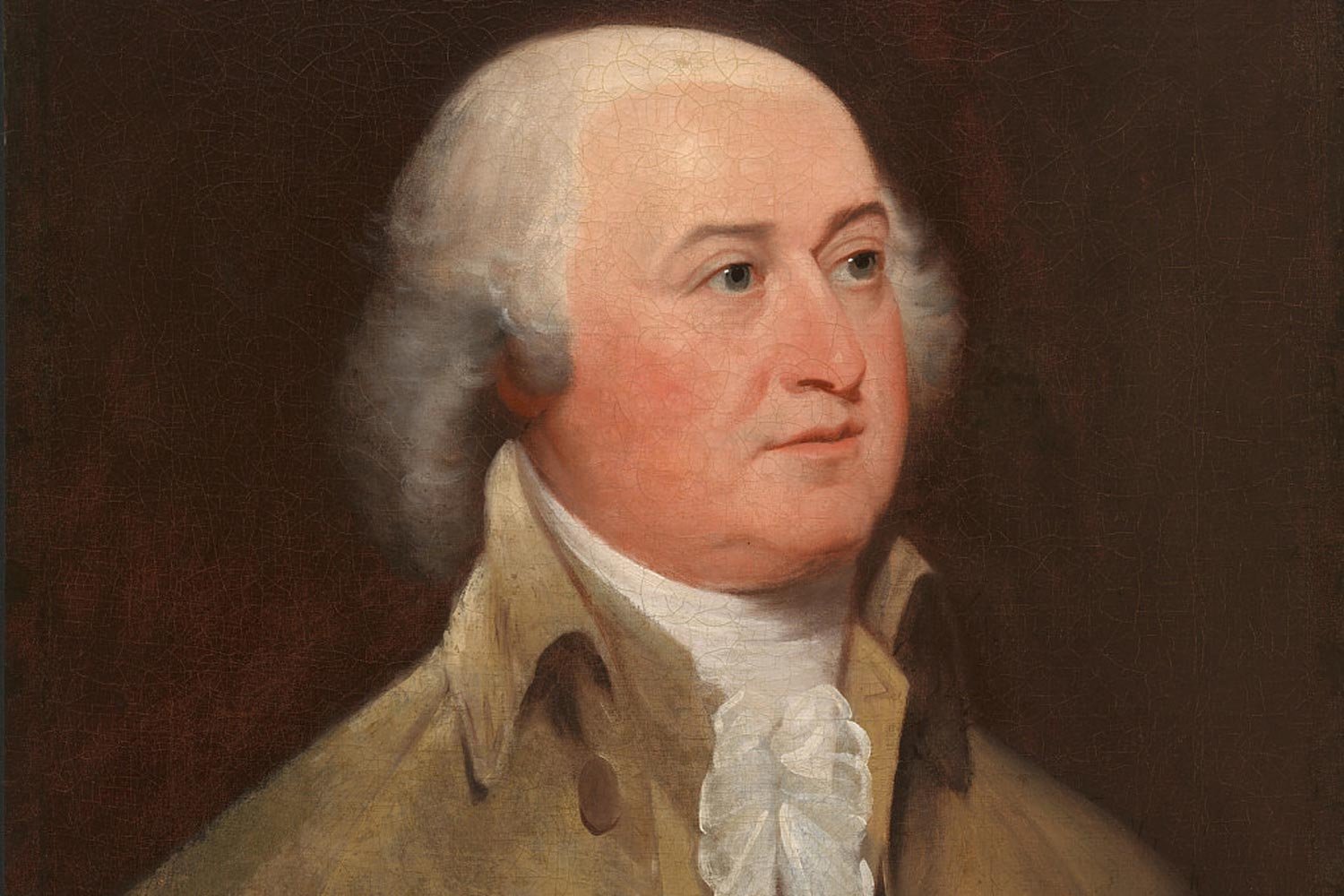

The disrespect shown to the United States by France in the XYZ Affair in the spring of 1798 pushed the Federalists who controlled Congress to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, a series of four laws, which President John Adams reluctantly signed into law in July. Posterity has viewed these measures harshly, but it is important to view them from the lens of 1798 and not modern times. At the time of their enactment, although many had reservations, the rationale behind them was not entirely groundless.

In 1798, France had been waging a very costly, undeclared naval war on the American merchant fleet for two years, an episode known to history as the Quasi-War. Because the United States had no navy, the country was helpless to respond and unable to defend its rights at sea. Furthermore, neither diplomacy nor pleading had been able to convince Revolutionary France to stop the depredations.

To add insult to injury, the French government had refused to receive Charles Cotesworth Pinckney as the United States Minister to France, an appalling diplomatic affront, and then followed that up with the bribe demands of the XYZ affair, which Americans found even more insulting. With the specter of war on the horizon and French belligerency increasing, there was a growing concern that the 25,000 French nationals then residing in the United States could cause revolutionary troubles in America like those in France.

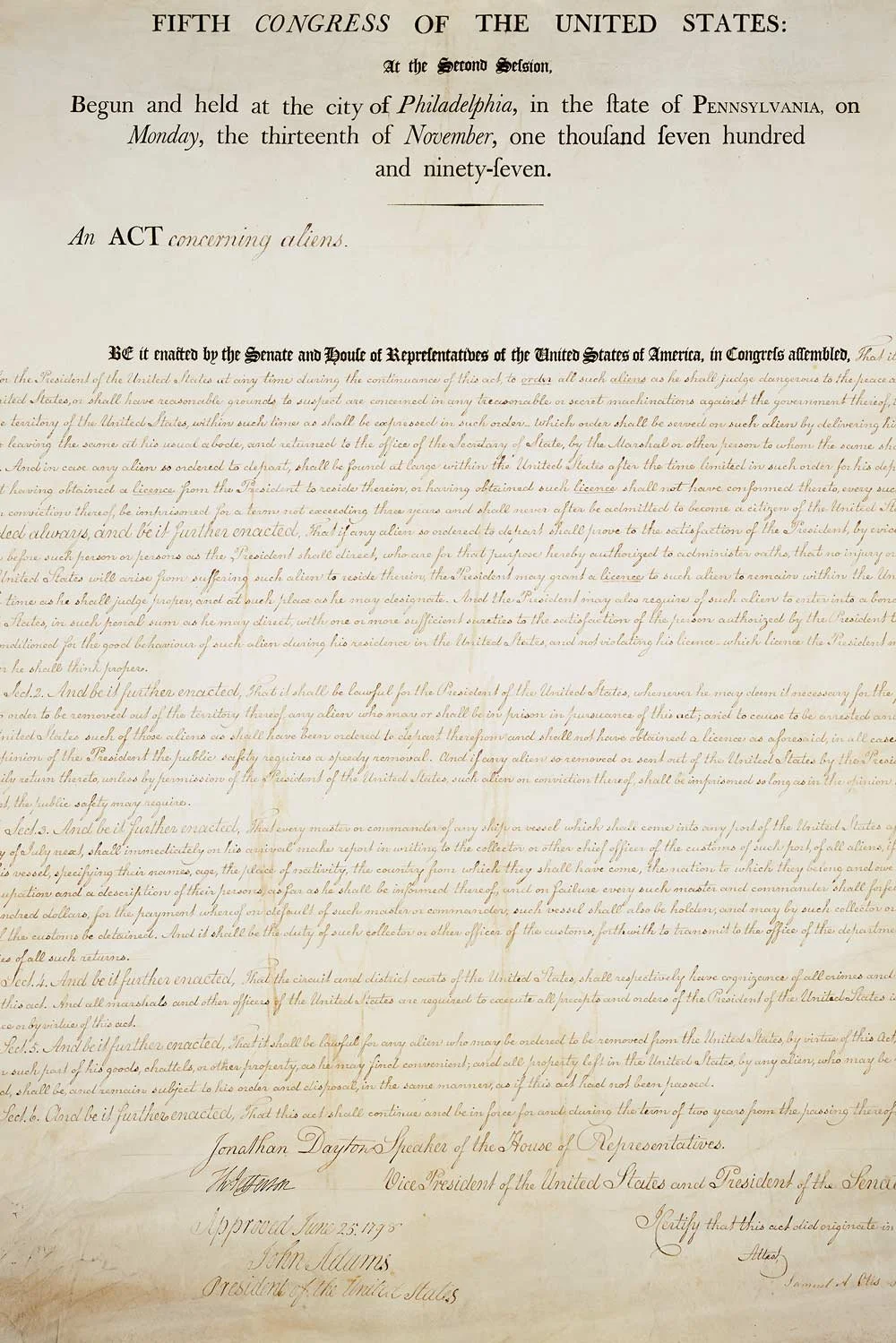

The four laws that constituted this legislation were the Naturalization Act, the Alien Friends Act, the Alien Enemies Act, and the Sedition Act. Although President Adams did not speak much on the subject at the time, he later wrote, “I knew there was need enough…and therefore consented to them.” As a package, Adams stated their purpose was national security, but there is little doubt that a corollary goal of the Federalists and the President was to suppress criticism of the Adams administration.

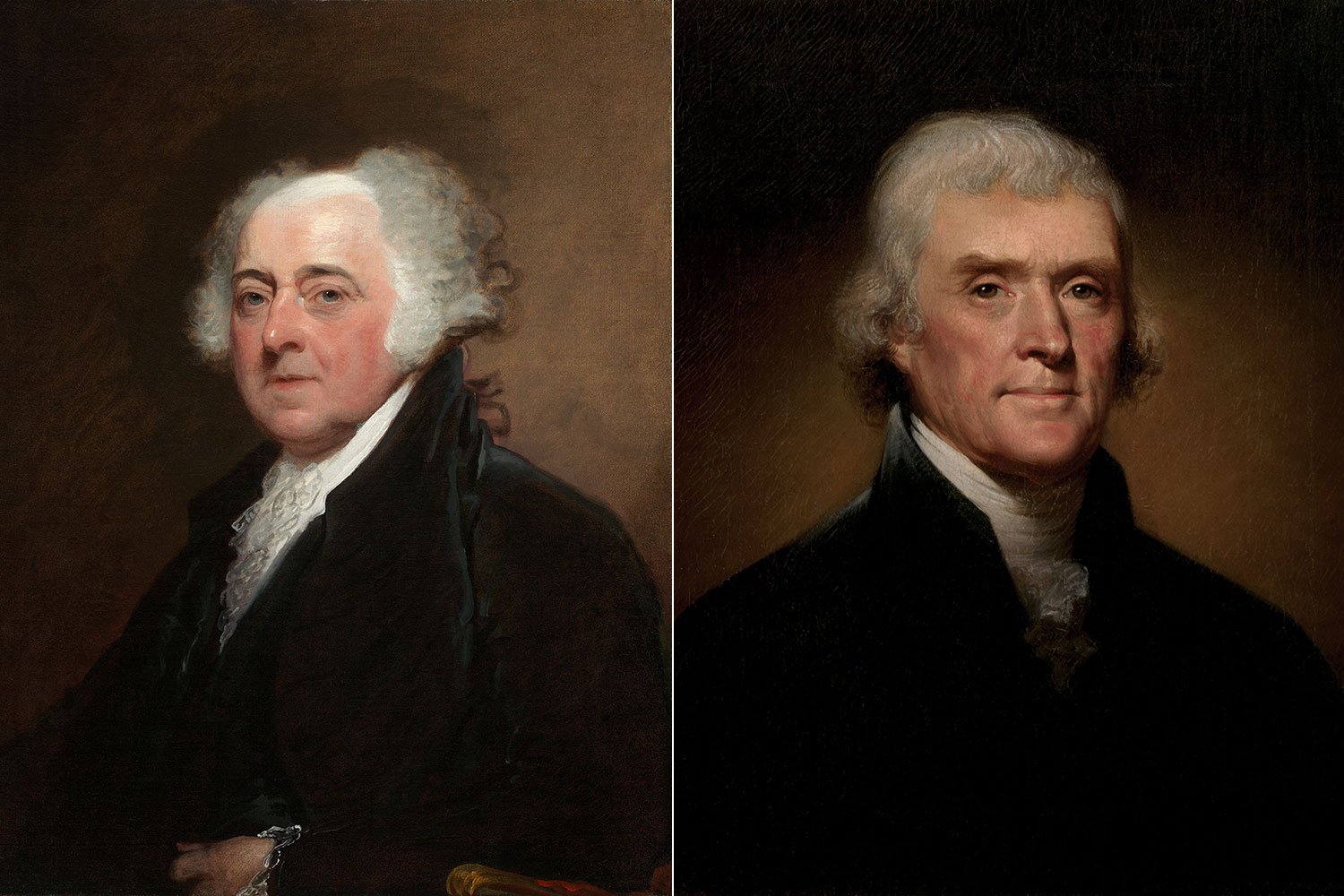

One of the Acts harshest critics was Vice President Thomas Jefferson who considered himself a strict Constitutionalist and stated the President could never rightfully violate that sacred document. Interestingly, five years later, when he was President Jefferson and completed the Louisiana Purchase, he admitted privately that he was exceeding his Constitutional authority. But he justified his actions in part on national security concerns and the need to secure the Mississippi River Valley for America. Jefferson discovered the world looks a bit different when you are the President.

The Naturalization Act increased the residency time required to become a citizen from five to fourteen years. It also stated that those desiring to become American citizens must declare their intention five years in advance of their citizenship date. This law was replaced by the Naturalization Law of 1802 which reverted the residency requirement back to five years.

The Alien Friends Act allowed the president to deport non-citizens who were considered “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States.” If a non-citizen was viewed as such, the President would be authorized to demand that they leave the country within a reasonable amount of time or face imprisonment. The law was never enforced, but it caused many French nationals to voluntarily leave the country. Interestingly, even those who were deemed a threat to the United States were never forcefully deported by President Adams, despite many Federalists including Timothy Pickering, his own Secretary of State, demanding he do so. The Alien Friends Act was allowed to expire in 1800.

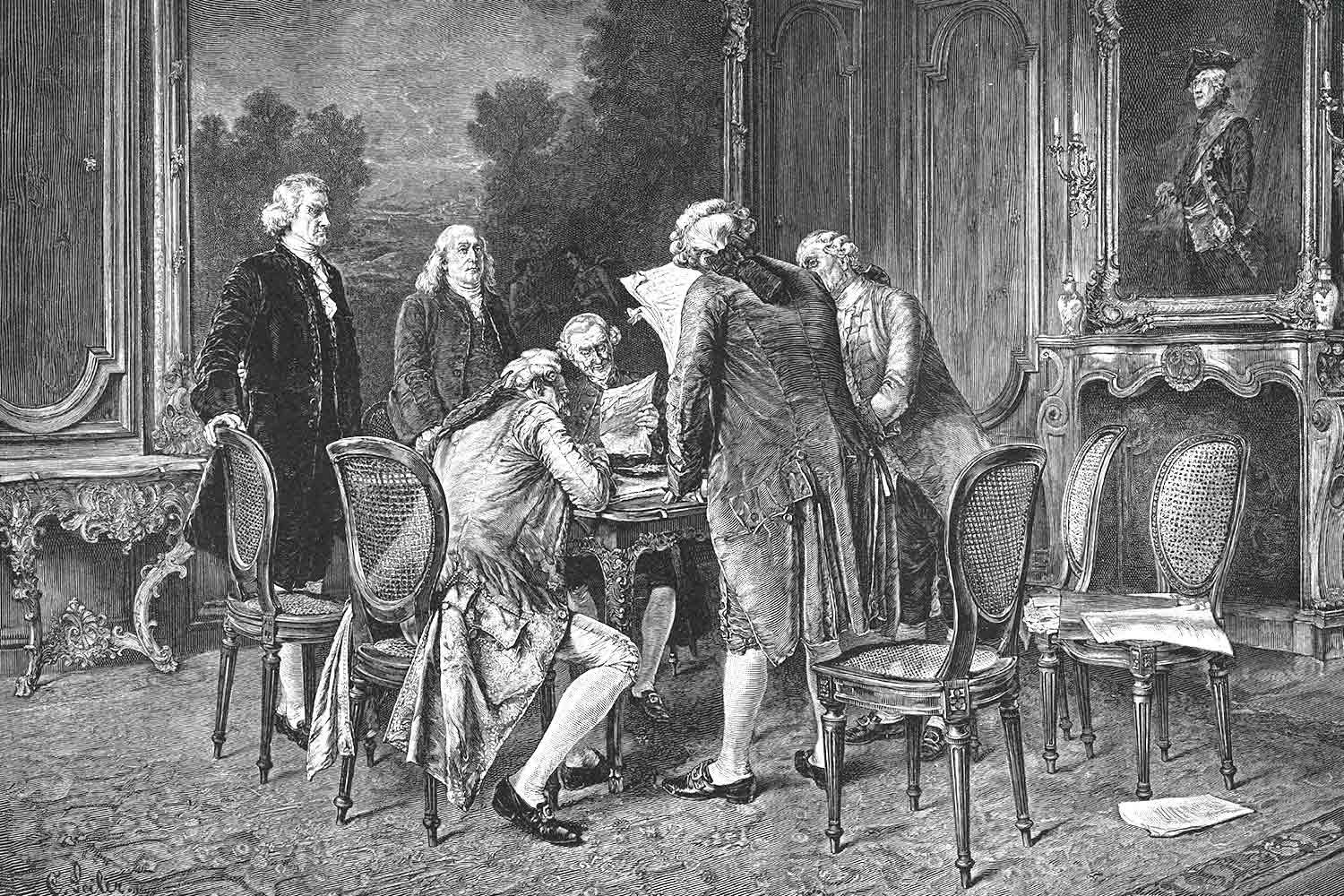

"Alien and Sedition Acts." Wikimedia.

The Alien Enemies Act was passed as a supplement to the Alien Friends Act. Its goal was to provide more authority to the President in time of war, and authorized the President to deport, imprison, or relocate any male over fourteen years of age from a nation with whom the country was at war. The Democratic-Republicans did not oppose this law.

Interestingly, the Alien Enemies Act is still in effect today, albeit with some slight modifications, and has been used by several Presidents over the years. President James Madison invoked it during the War of 1812 and President Woodrow Wilson did so in World War I, going so far as to apply the law to women as well. In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt used the Alien Enemies Act to detain and imprison German, Japanese, and Italian non-citizens. Even President Harry Truman used the law’s provisions to deport enemy aliens from Latin America in 1945.

However, it was the Sedition Act that generated the most controversy in 1798. This legislation made it illegal to make “false, scandalous, or malicious” statements about the government, Congress, or the President or “to excite against them…the hatred of the good people of the United States or to stir up sedition.” The law passed the House by just three votes, and only after a clause was inserted that automatically terminated its provisions in March 1801.

This act was clearly a violation of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. But many prominent Federalists felt something had to be done to stop the lies and unjustified verbal assaults Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican newspapers were spewing about the government while the country was in a state of war, even if the war was undeclared.

This attack on First Amendment rights angered many people including Vice President Jefferson, who pushed back against the measures.

Next week, we will discuss the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.