The Presidency of John Adams

To avoid a war with France, in 1797, President John Adams sent a diplomatic delegation to Paris to calm rising tensions. This team consisted of John Marshall, Charles Pinckney, and Elbridge Gerry.

When our team arrived in France in October 1797, they were approached by three French officials whose code-names were X, Y, and Z. These Frenchmen demanded large bribes from the Americans for themselves and other French officials before negotiations could start.

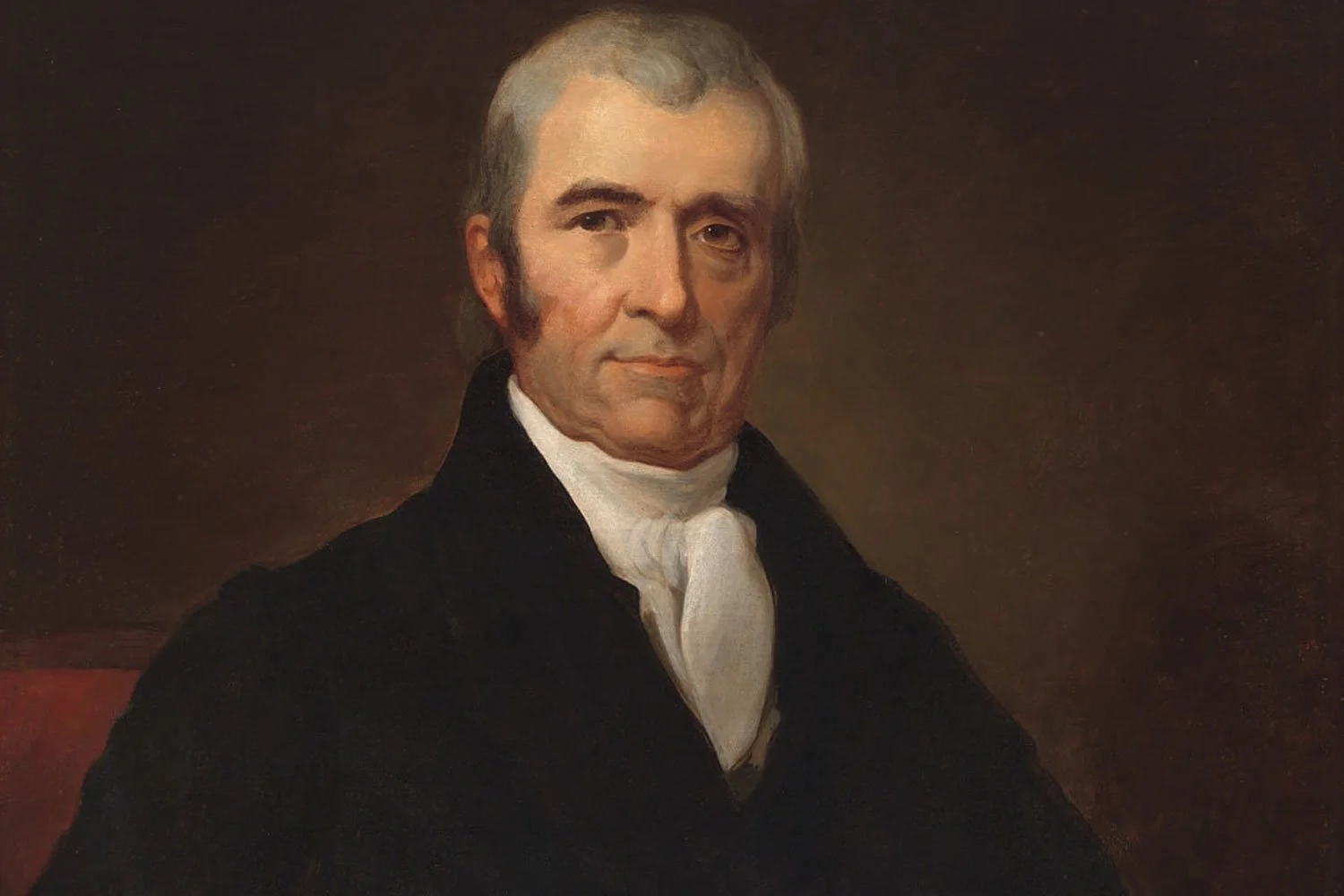

James Reid Lambdin. “John Marshall.” National Portrait Gallery.

The Americans were outraged and refused to pay anything to the French. Pinckney famously replied, “No, no, not a sixpence” and Marshall quickly sent dispatches relating this affair to President Adams. After several months of fruitless discussions and no bribe payment, Marshall and Pinckney sailed for home (Gerry decided to stay behind).

When President Adams received Marshall’s summary of the discussions on March 4, 1798, including the French bribe demands, Adams withheld the documents. He was worried releasing them would only heighten tensions in the United States. Republicans who opposed his Federalist party assumed his refusal to release Marshall’s papers was an attempt to cover up missteps by our delegation.

On April 3, 1798, Republicans in the House demanded the papers be released and President Adams complied. Everyone, especially the Republicans, were stunned at the actions of the French. This episode, named the XYZ Affair, quickly turned public opinion against the French and strengthened Federalist arguments to build up our army and navy.

With diplomatic negotiations at a standstill, France increased their attacks on American ships in the spring of 1798. Consequently, on July 7, 1798, Congress authorized the use of military force on France and re-established the United States Navy and Marines. President Adams named Benjamin Stoddert the first Secretary of the Navy.

The resulting series of engagements on the high seas is known as the Quasi-War, a sort of undeclared naval war between France and the United States. Mostly fought in the Caribbean and in American coastal waters, this conflict finally ended with the Convention of 1800 when Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France and decided to end the conflict.

The terms of the Convention essentially solidified the neutrality of American merchant ships on the high seas and officially ended the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France. However, the French refused to compensate Americans for losses estimated at $20,000,000 incurred during the Quasi-War.

The enflamed passions caused by the XYZ Affair also pushed Federalists to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, a series of four laws, which President Adams reluctantly signed in June 1798. The Naturalization Act increased the residency time required to become a citizen from five to fourteen years. The Alien Friends Act allowed the President to imprison and deport non-citizens who were deemed a threat to the country.

The Alien Enemies Act allowed the President to do the same to any male over fourteen years of age from a nation with whom we were at war. Interestingly, this law is still in effect today. However, it was the Sedition Act, which criminalized speech critical of the federal government, that generated the most controversy.

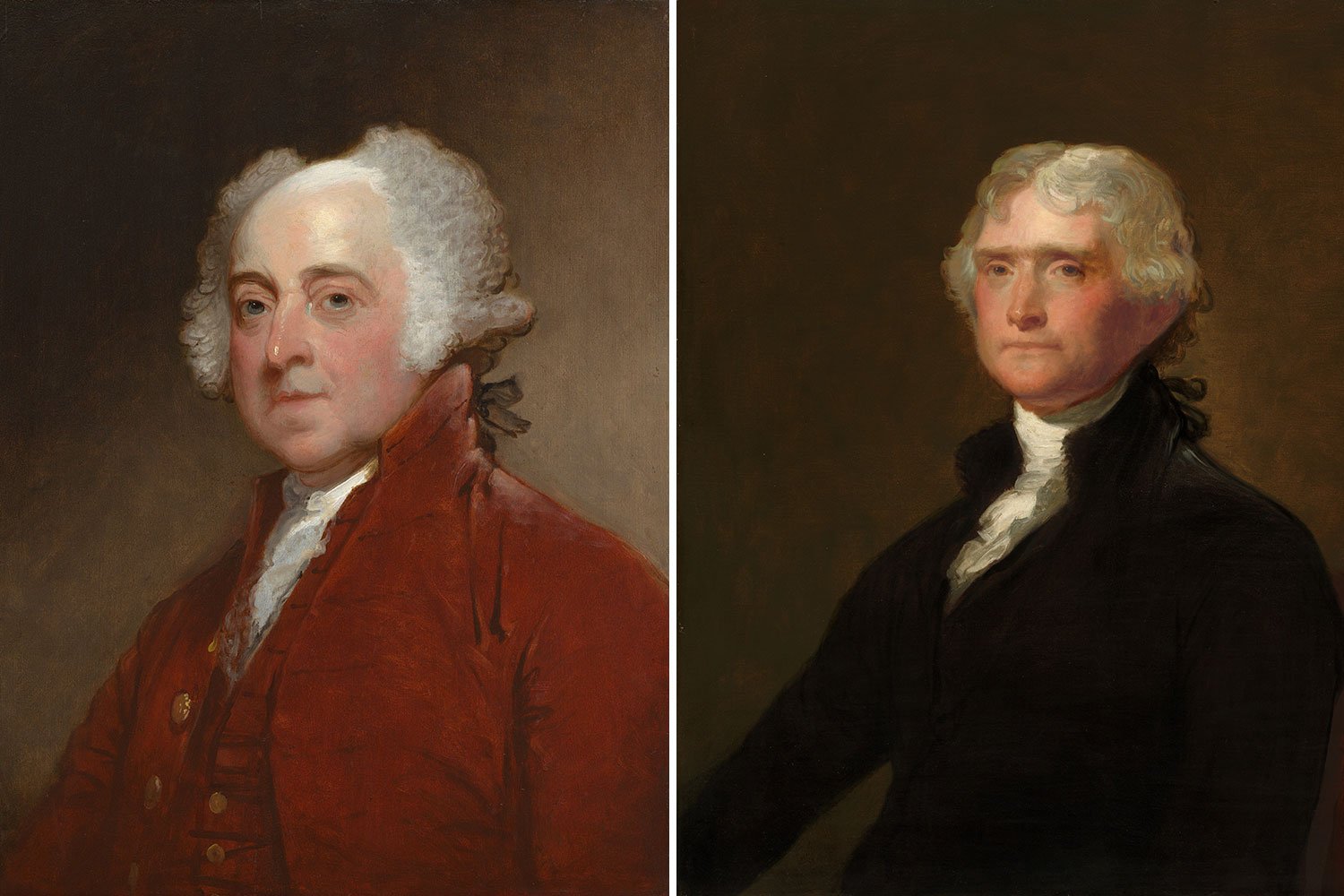

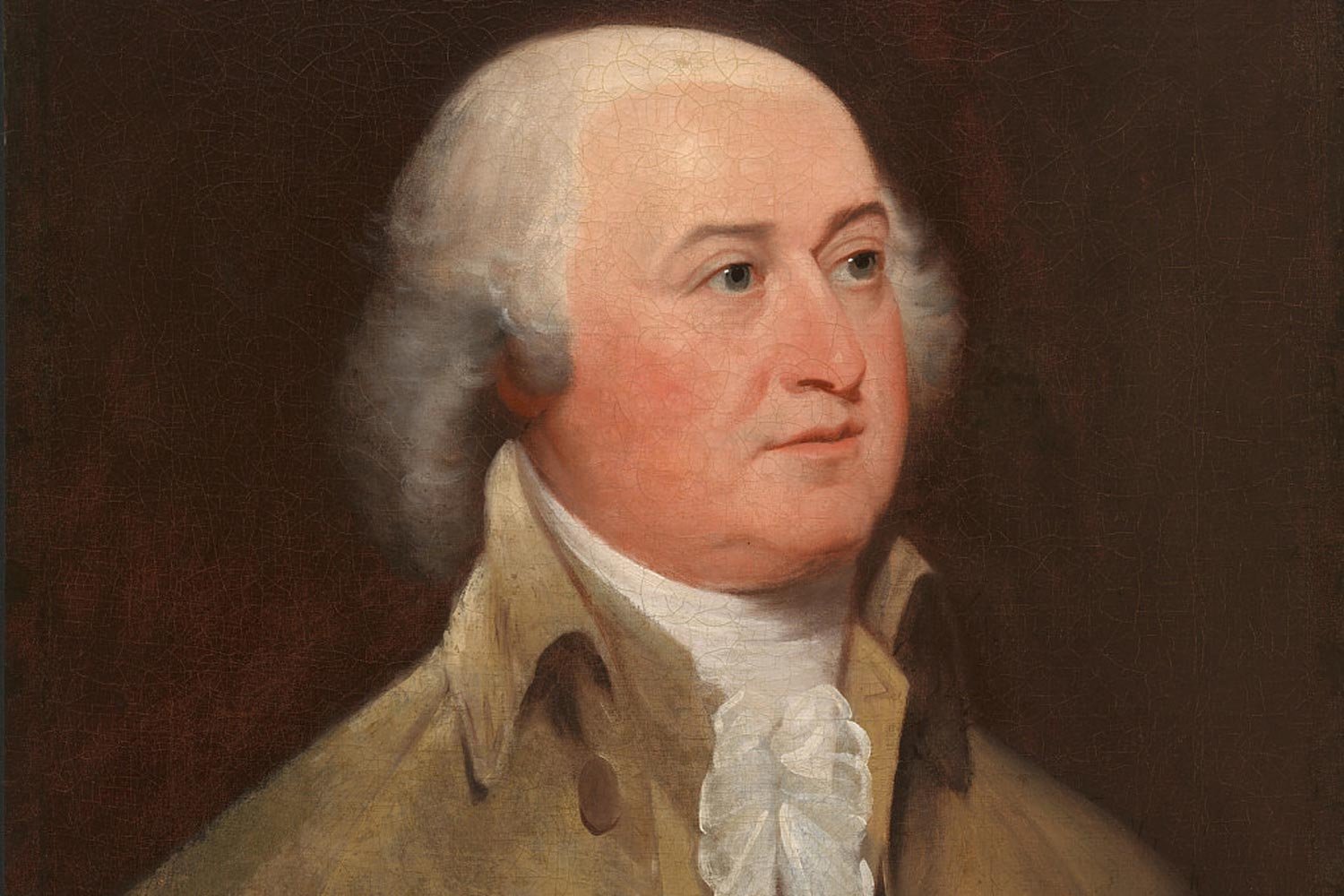

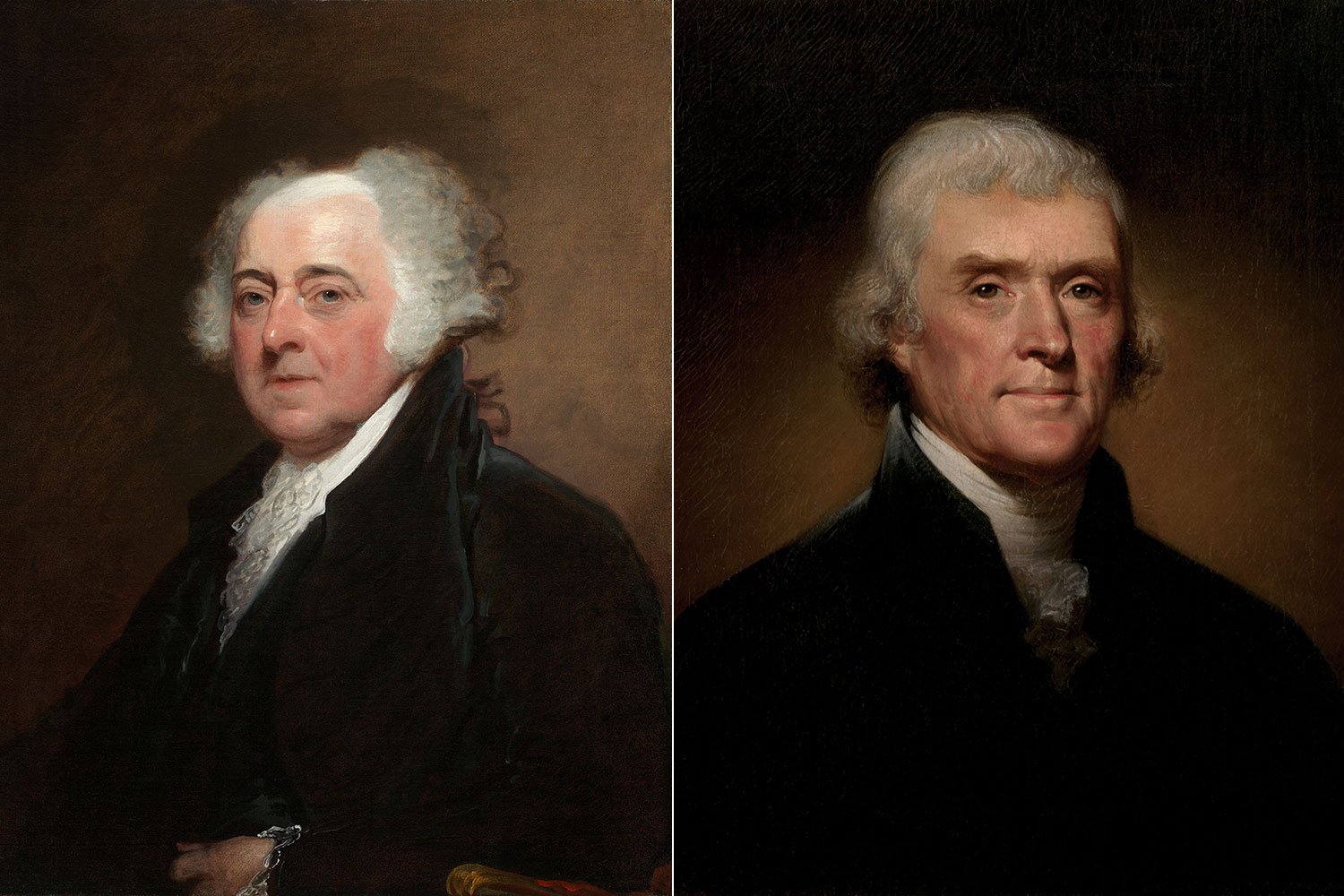

This first ever attack on First Amendment rights was widely criticized and turned many people against the Adams administration. This displeasure was exploited by the Republicans in the election of 1800 which pitted the Federalist’s President Adams against the Republican Party’s Thomas Jefferson.

To make matters worse, Alexander Hamilton, supposedly a political ally of President Adams since both were Federalists, worked behind the scenes to defeat Adams. Hamilton, who had been very influential with President Washington, had expected to be even more so with President Adams. It did not work out that way as Adams proved to be independent and very much his own man.

Consequently, Hamilton decided to back Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina, a more pliable man, for President. Hamilton quietly convinced some Federalist electors to vote for Pinckney but not Adams.

This plan backfired as Hamilton’s scheming helped elect Thomas Jefferson, the man Hamilton detested more than anyone else. When the final tally was counted, Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied with 73 electoral votes (Jefferson was eventually elected President by the House of Representatives), Adams received 65, Pinckney 64, and one elector voted for John Jay.

Next week, we will discuss the final days of the Adams Presidency, his retirement years, and John Adams’ legacy. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.