An Expression of the American Mind

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.

“Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

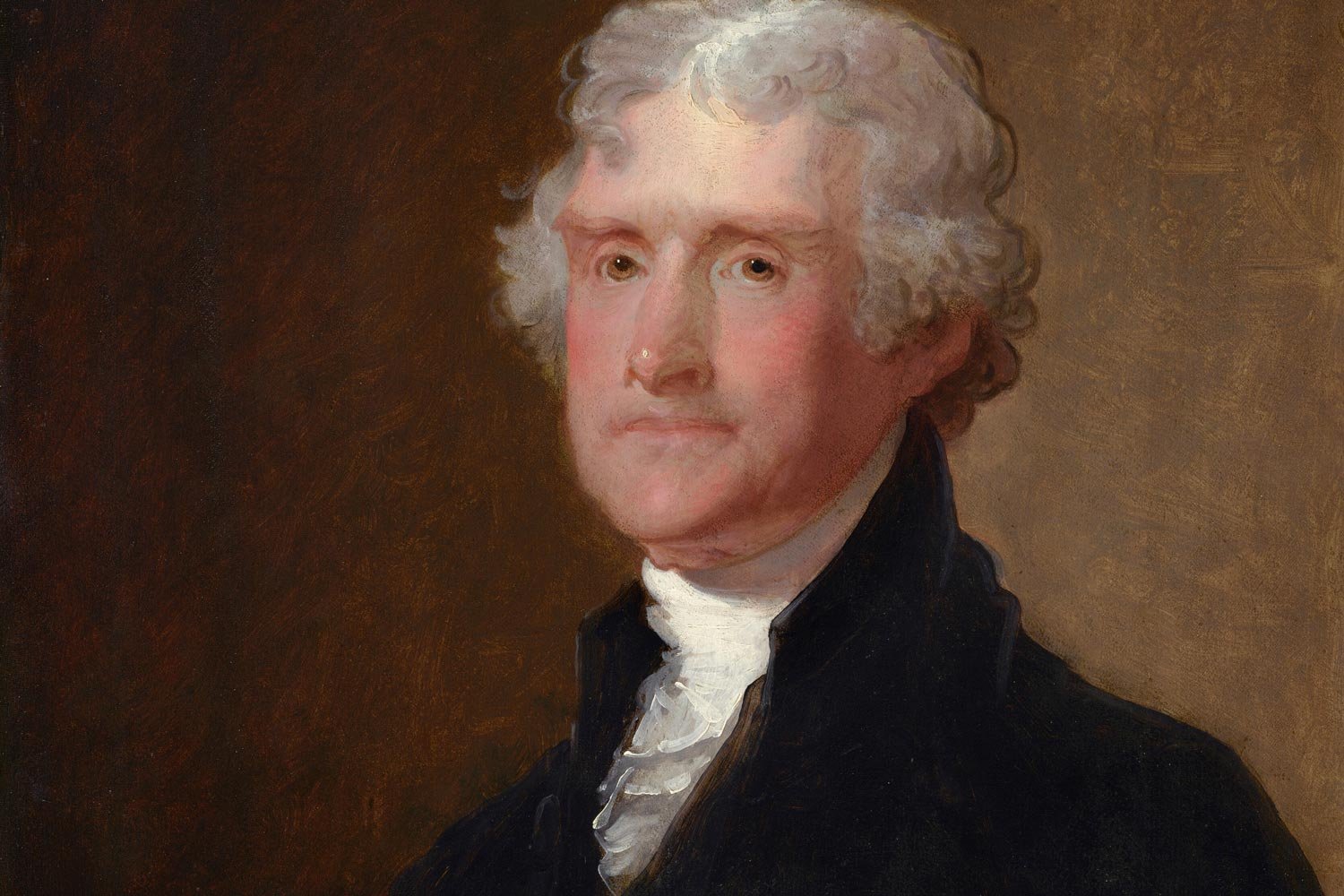

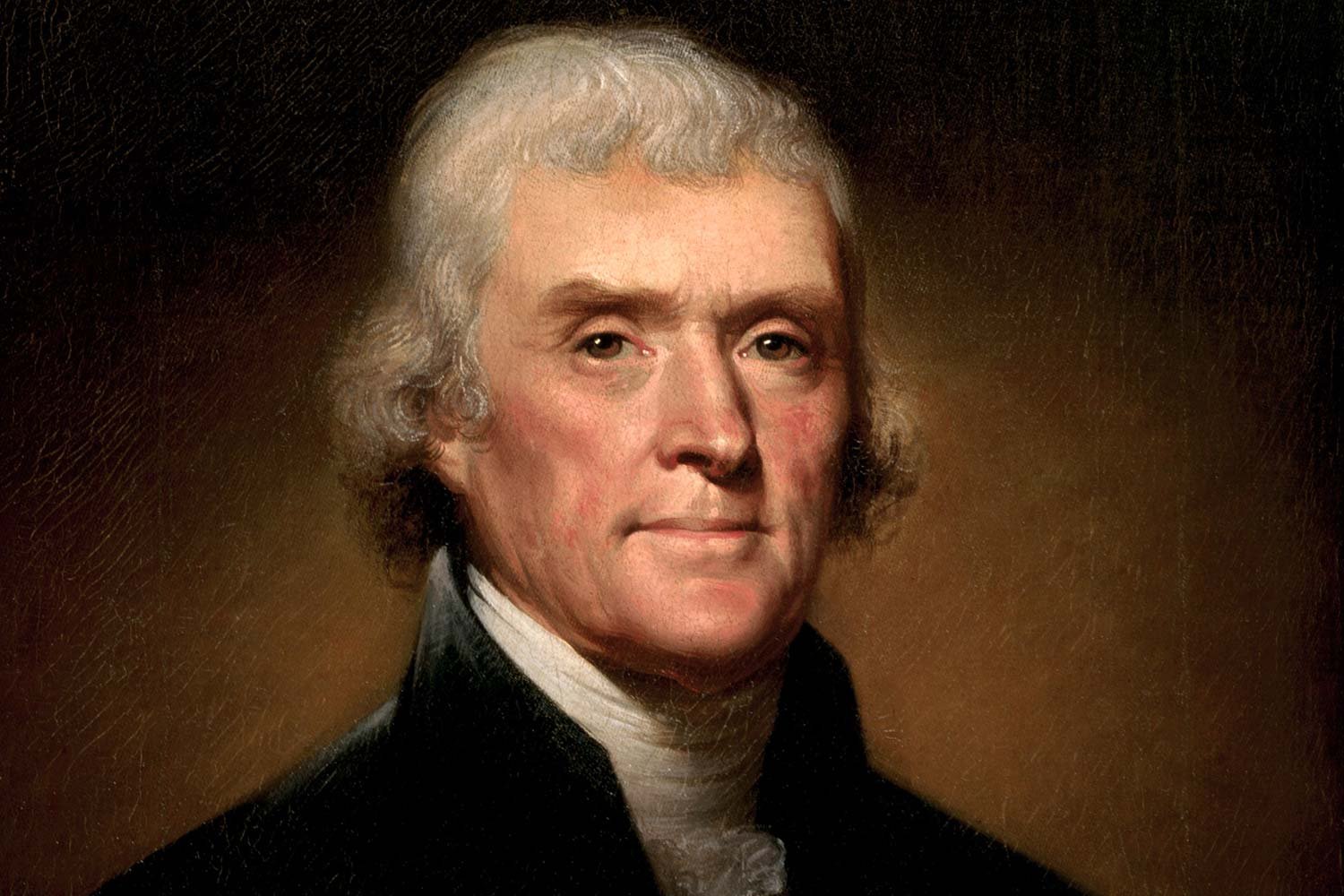

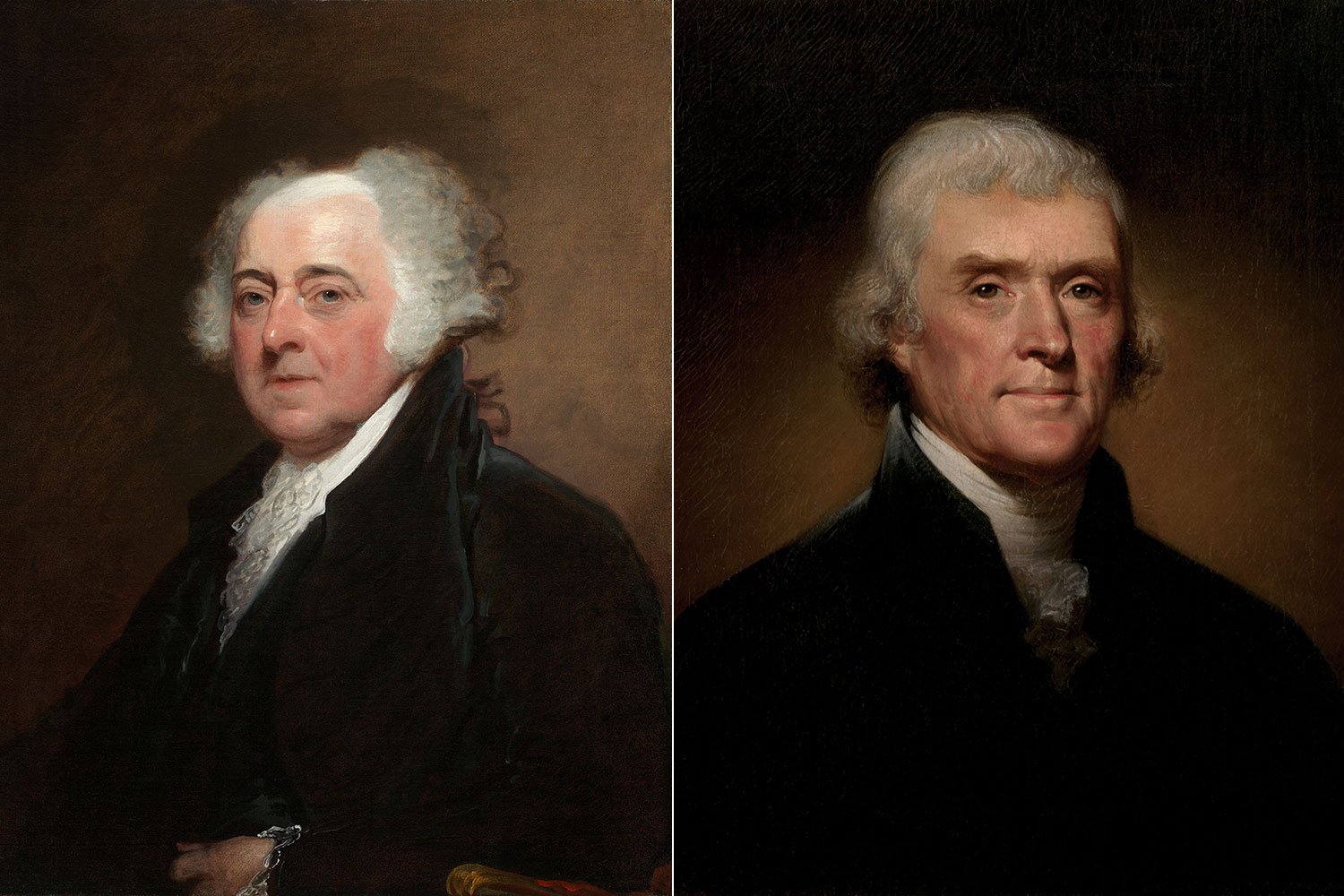

This leap of faith into the unknown space of independence had finally been publicly demanded; the topic that many did not want to openly debate was now before Congress and had to be addressed. Following two days of contentious debate, it was decided to table the discussion until July 1, but Congress created a committee to draft a declaration of independence in the event they chose that course of action. The committee included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Robert Livingston, Roger Sherman, and Thomas Jefferson. This Committee of Five in turn selected Jefferson to be the main penman of the declaration as Jefferson’s writing style was exceptional and, as John Adams stated, it had a “peculiar felicity of expression.”

From June 13 to June 28, Jefferson isolated himself in his two rooms at the boarding house where he was staying in Philadelphia, working diligently to perfect his draft that was destined to become arguably the most famous document in American history. As Jefferson later explained, he was not attempting to create novel concepts or legal reasonings, but rather “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take…it was intended to be an expression of the American mind.”

Jefferson opens with an explanation that the country is making this declaration out of a sense of respect to all the peoples of the world. “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Although a lawyer by trade, Jefferson was very much a man of science and as such he followed a scientific literary method known as a syllogism, with a major premise, a minor premise, and a logical conclusion that flowed from their connection. Jefferson presents his major premise that there exists in nature and among mankind several settled truths. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

He goes onto to explain how these inalienable rights are secured by the people, and the recourse to be taken if these rights are violated. “That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to abolish it, and to institute new government…most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”

Next comes Jefferson’s minor premise which is a list of twenty-seven specific grievances against the King and Parliament demonstrating that they have violated the aforementioned rights of their American colonists. Jefferson starts with complaints against the king…

“He has dissolved representative houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions of the rights of the People.”

“He has obstructed the administration of justice, by refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers.”

…and then moves on and complains of Parliament:

“For cutting off our trade with all parts of the world:

“For imposing taxes on us without our consent:

“For depriving us in many cases of the benefits of trial by jury.”

Jefferson explains how American colonists have repeatedly tried to remedy issues through non-violent methods but that all petitions for redress have been ignored. “In every stage of these oppressions we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms: our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.”

Currier & Ives. “The Declaration Committee.” Library of Congress.

Jefferson closes with the logical conclusion that flows from his two premises. “We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America…by authority of the good people of these colonies, solemnly publish and declare, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is and ought to be totally absolved.”

On June 28, Jefferson presented his draft to the Committee of Five for their review. Franklin and Adams made a suggestion or two, but for the most part left Jefferson’s masterpiece intact. That was not the case when Jefferson’s work was presented to Congress on July 1. For three days, Jefferson’s fellow delegates critiqued his work, an excruciating painful experience for the hyper-sensitive Jefferson.

As with some of his previous writings in Virginia, Jefferson’s concepts were too radical and his words too harsh for the more cautious members of Congress. Many of his strongly worded grievances against King George were watered down or completely omitted by more conservative men. Most notably, Jefferson’s severe criticism of the King for his part in the slave trade was completely stricken from the Declaration, largely at the insistence of delegates from South Carolina and Georgia. This rebuff was nothing new to Jefferson, who had been unsuccessful in his several attempts to pass legislation to end the slave trade in Virginia.

In any event, on July 4, 1776, Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was adopted by Congress and was read aloud in courtyards and town squares across the land. Despite the editing, Jefferson was proud of it, and, when he wrote his own epitaph, the first thing he listed in his accomplishments was the Declaration of Independence.

Next week, we will discuss the Louisiana Purchase. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.