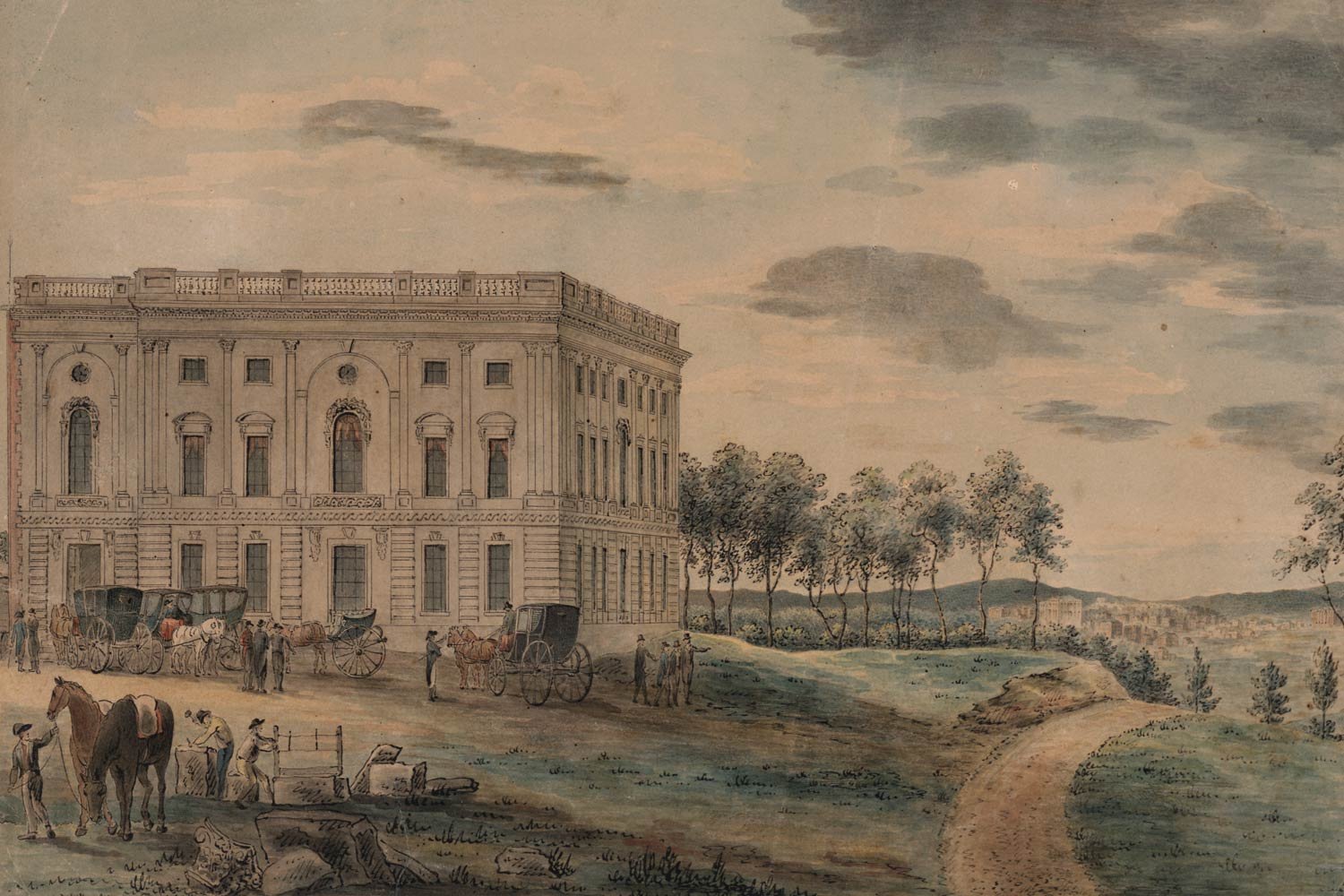

The House of Representatives Chooses Thomas Jefferson

The presidential election of 1800 ended in a tie, as the two Democratic-Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, each received 73 electoral votes under the original guidelines of the Constitution. The result came as a shock to the Democratic-Republicans, who added Burr to their party ticket solely to carry his home state of New York in the election. That part worked out and the state flipped from Federalist to Democratic-Republican, but they had assumed that Jefferson would get the most votes and Burr the second most. Fortunately, the men who framed the Constitution had foreseen this possibility and had created a provision for just this scenario. But the way events subsequently played out were so alarming that they led to an amendment to the Constitution.

Article 2, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution states that if “there be more than one (candidate) who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately choose by Ballot one of them for President.” The clause further states that each state delegation shall have one vote, regardless of its population or representation in Congress.

At the time of the election, there were sixteen states in the Union so Jefferson or Burr needed to receive the vote from at least nine states to gain a clear majority and win the election. Importantly, the outgoing Congress which was controlled by the Federalists would do the voting instead of the incoming one which was to be dominated by the Democratic-Republicans. This mattered because it essentially meant that the party which lost the election would choose the next President.

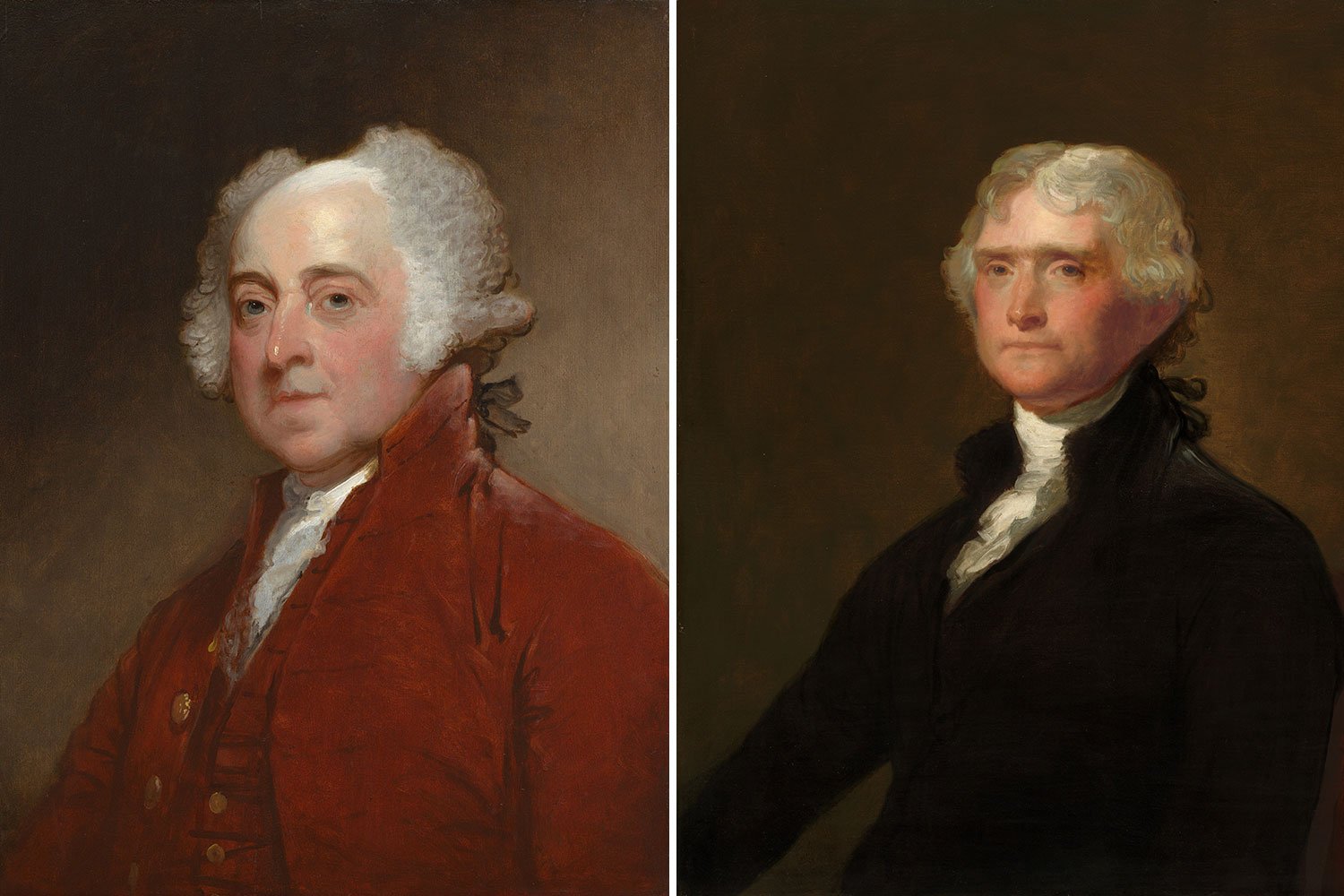

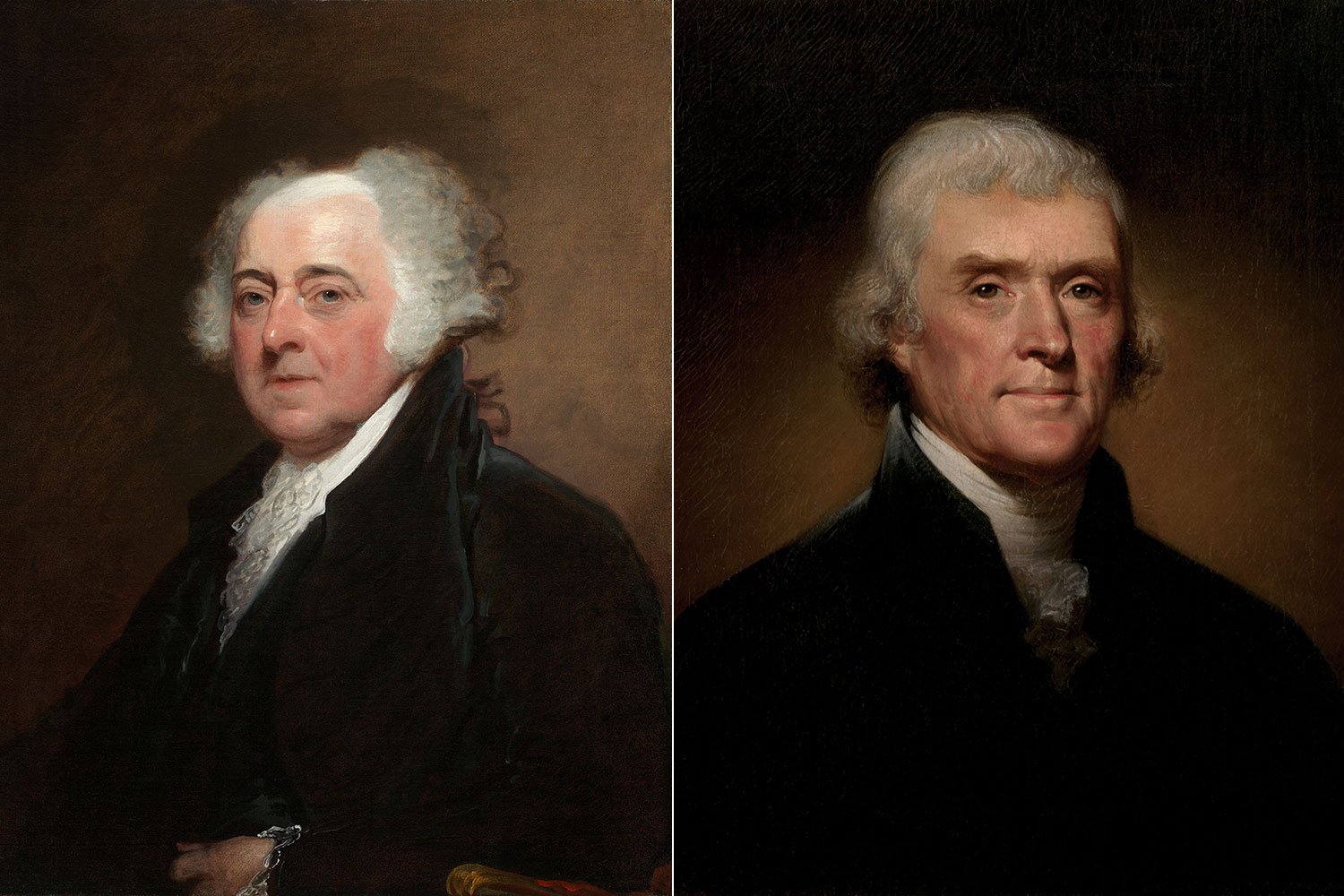

In the eyes of most Federalists, Jefferson was practically the devil himself and the arch enemy of the country and the Constitution. John Marshall, the recently appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court, did not know Burr but he knew Jefferson, his cousin, and he detested him. Marshall had stated to outgoing President John Adams that Jefferson was a man of low character and would “sap the fundamental principles of government” if given the chance.

Alexander Hamilton, the leader of the Federalist Party, had had a long running bitter feud with Jefferson that extended back to their time in President George Washington’s cabinet, as Secretary of the Treasury and Secretary of State, respectively. It was their animosity towards each other that in part forced Washington to accept a second term as president, as Washington was fearful of what mischief they would create if he were not around to mediate. But Hamilton still thought Jefferson was the better choice despite his friendly relations with Burr. That of course would change in the years ahead and lead to the infamous Burr-Hamilton duel in Weehawken, New Jersey in 1804, resulting in the death of Hamilton.

To bring his adherents in line, Hamilton began a letter writing campaign informing Federalist congressmen of his support for Jefferson. In one letter, Hamilton wrote “if there be a man in the world I ought to hate, it is Jefferson” but that the “public good must be paramount to every private consideration.” While Jefferson had only “pretensions to character,” Burr had none at all. In Hamilton’s opinion, Burr was “daring enough to attempt everything – wicked enough to scruple nothing.” Hamilton’s judgement of Burr’s character would be justified later when Burr treasonously attempted to separate the western states and territories from the rest of the country.

Burr knew Jefferson was the intended candidate but refused to withdraw from consideration, especially when he was unexpectedly so close to the prize of the Presidency. Democratic-Republicans, especially Jefferson, never forgave Burr for his duplicity in this affair. In later years, Burr was an outcast from the party and was not reselected as Jefferson’s running mate in the election of 1804.

On February 11, 1801, Congress convened in accordance with the Constitution and cast its first set of ballots to settle the election. Jefferson carried eight states, Burr received six votes, and two delegations, Maryland and Vermont, were tied and, therefore, were forced to cast blank ballots. Thus, Jefferson was one vote short of a clear majority of nine. Another vote was taken but with the same result and then another and then another until, over the course of six days, a total of thirty-five ballots were cast, but the count was always the same.

Rembrandt Peale. “General Samuel Smith.” Wikimedia.

Finally, on February 17, a deal was struck between Representative James Bayard, a moderate Federalist from Delaware, and Representative Samuel Smith, a Democratic-Republican from Maryland. Bayard and his Federalist colleagues agreed to change their votes from Burr to “no selection” which turned the tie votes in the Maryland and Vermont delegations into Jefferson wins, thus giving Jefferson ten votes and the presidency. In return, Jefferson, who declared publicly he would never make any deals, agreed privately to retain select Federalist office holders in their current positions.

Interestingly, this near disaster, coupled with the 1796 presidential election which saw the president and vice president being selected from opposing parties, led to the passage of the Twelfth Amendment. This amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1804 and required Electors to cast one ballot for president and a separate ballot for vice president.

The election, sometimes called the “Revolution of 1800,” ushered in the Jeffersonian Era in which Thomas Jefferson and his two Virginia proteges, James Madison and James Monroe, were all successively elected to the presidency, each for two terms. This Virginia dynasty spanned twenty-four years and represented both a geographic and a political dominance that has never been repeated in our country’s history. Six straight presidential elections saw men elected from the same state, Virginia, and six straight times the people chose the same party to lead the country, Democratic-Republicans.

More importantly, this era represented a seismic shift for the country away from the Federalist party which arguably leaned aristocratic to a more republican form of government that gave “the people” a greater say in how the country would be run. The last remaining bastion of Federalist power was Chief Justice John Marshall and the Supreme Court, and in the first quarter of the 19th century, these Democratic-Republican presidents would square off repeatedly in historic legal battles with the Chief Justice.

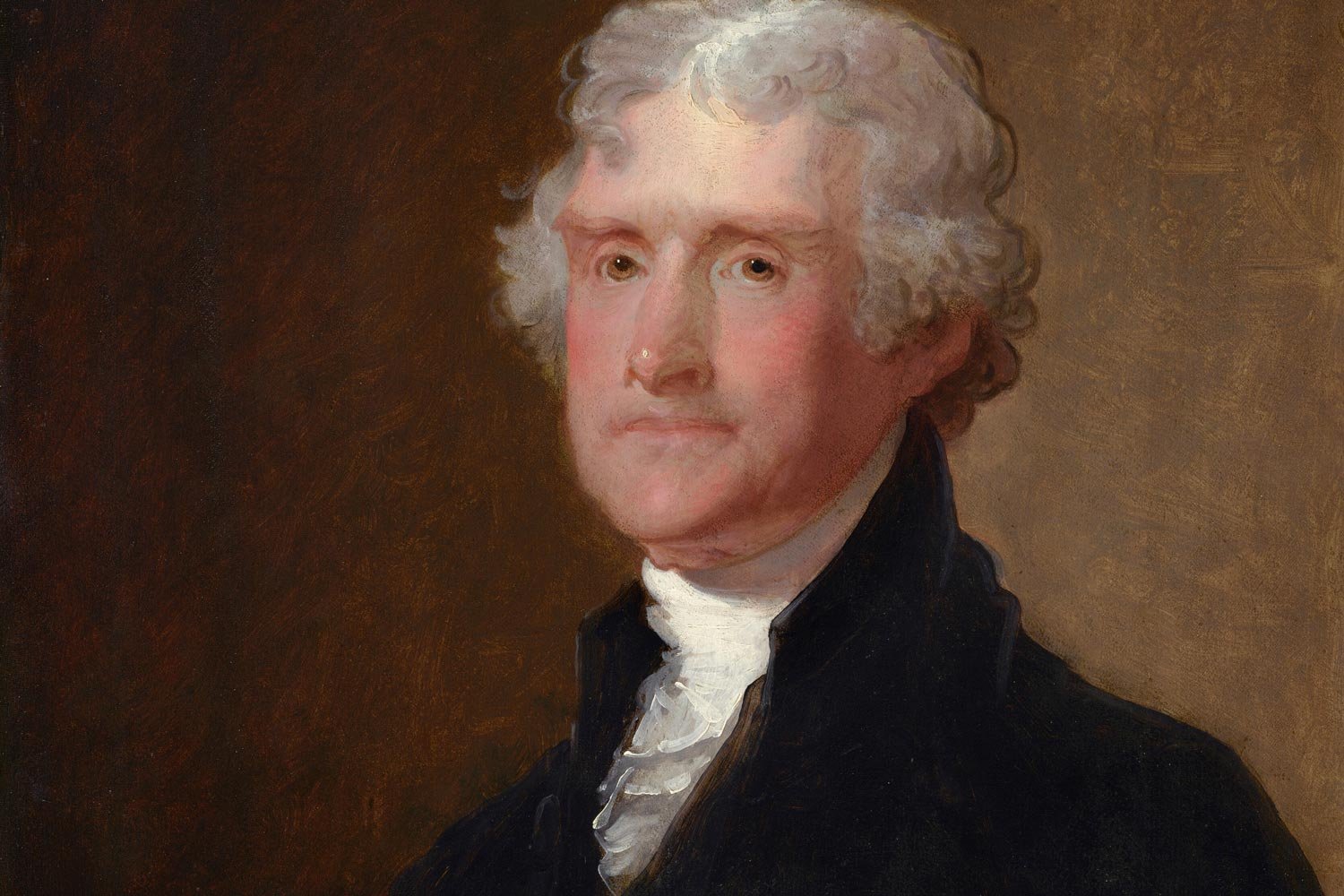

Thomas Jefferson, the man at the center of these monumental changes, seemed an unlikely candidate to champion “the people” given his aristocratic tendencies. But this iconic American was a complex man from an early age.

Next week, we will discuss the early life of Thomas Jefferson. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.