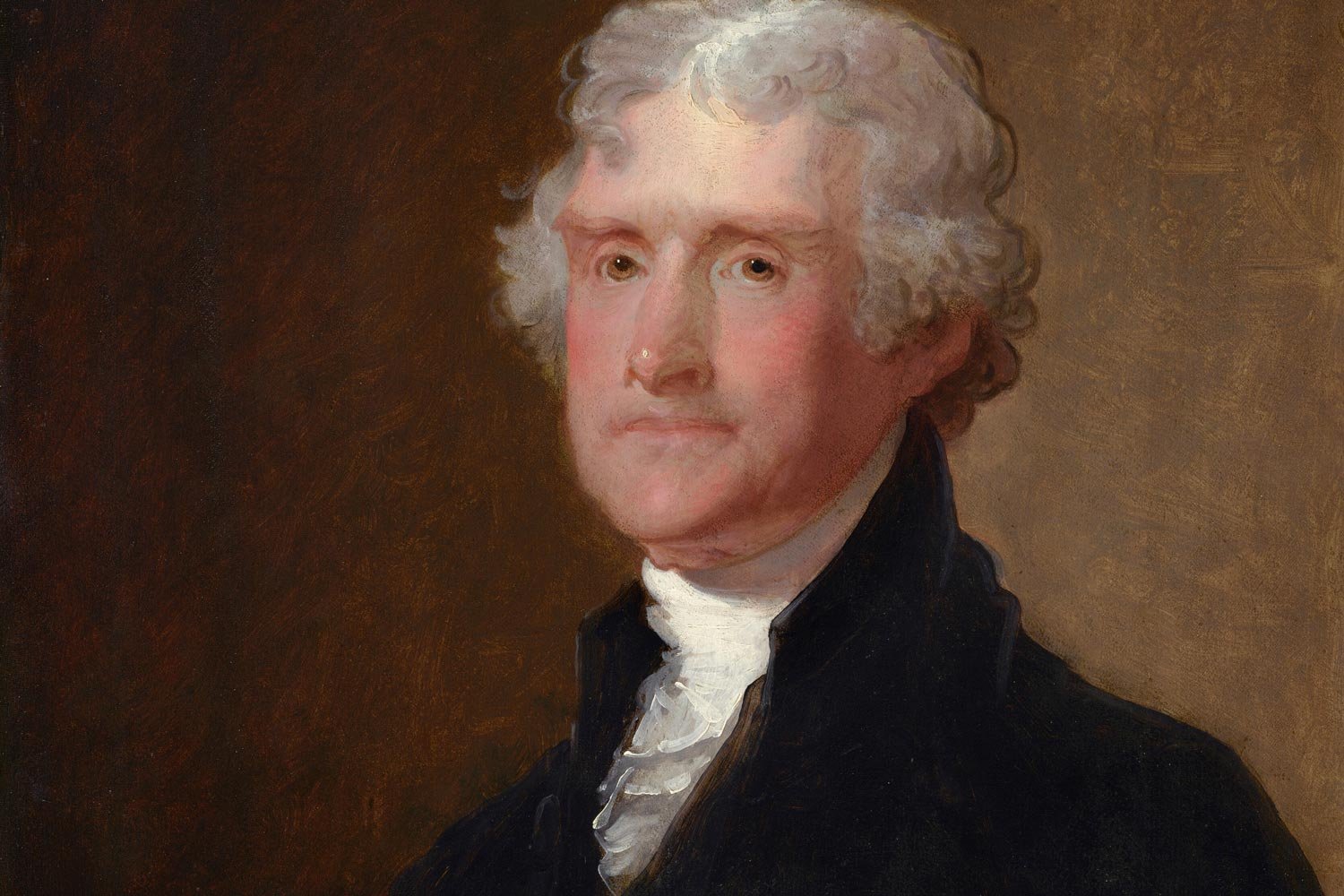

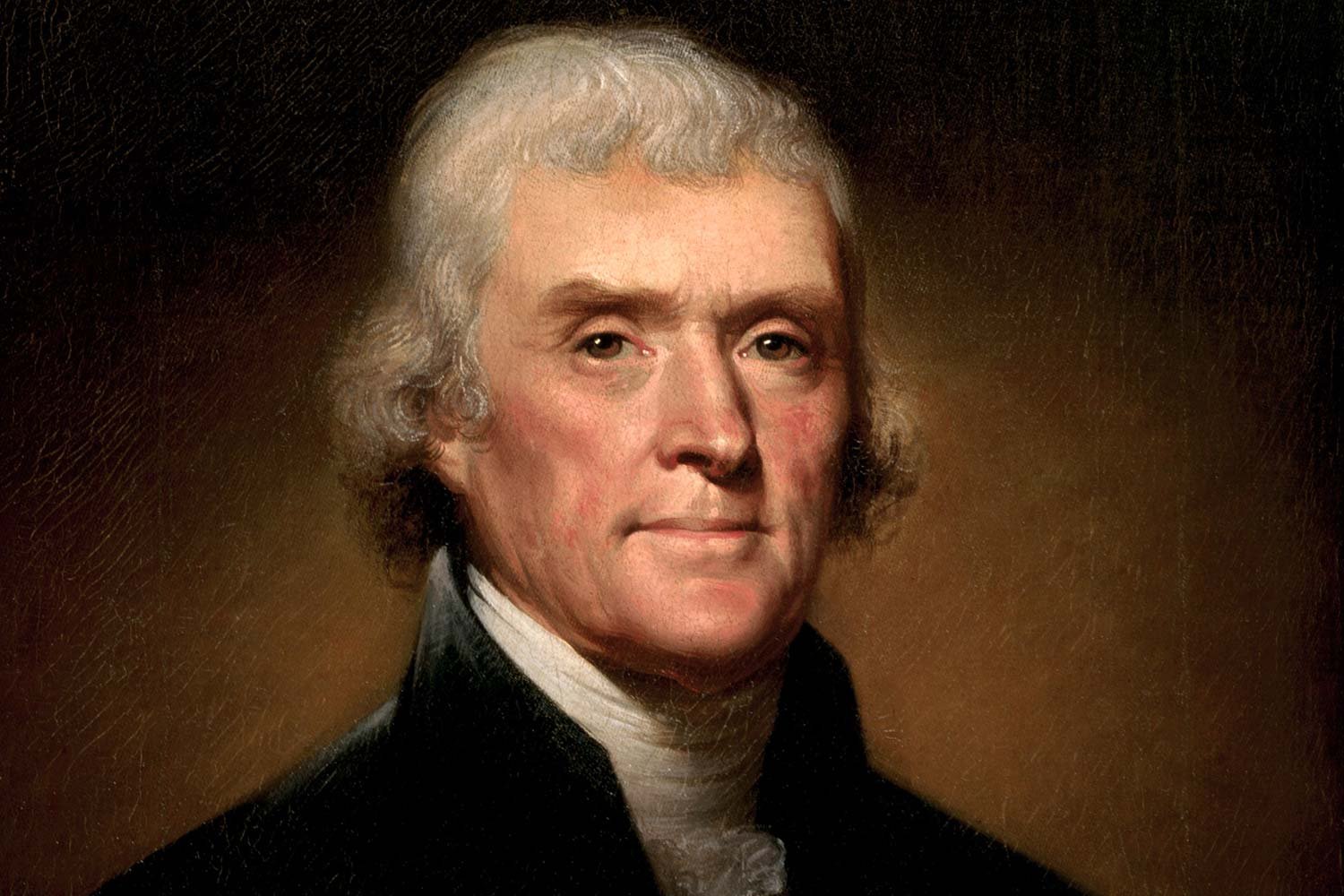

Thomas Jefferson, the Virginia Barrister

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the first internal tax on the American colonies, and thus began a decade of missteps by the British. Their miscalculations would take their country and their colonists on a direct path to Lexington Green and Concord Bridge on April 19, 1775. During this same year, Thomas Jefferson was concluding his time studying law under George Wythe and began to turn his eye towards the world at large and, more specifically, politics in the Colony of Virginia. The timing would prove to be most fortunate for the country as Jefferson would lend his considerable skills to the political maelstrom that was about to be unleashed.

The Stamp Act placed a tax on virtually all printed paper goods used in the colonies, items such as newspapers, playing cards, almanacs, diplomas, pamphlets, legal documents, and insurance policies. Prior to this Act, the colonies had been permitted to determine internal taxation policies in accordance with their founding charters, while the Crown had determined taxes on external matters such as custom duties on imported goods.

Not surprisingly, the reaction by the colonists to this encroachment on their established liberties was immediate and widespread across all the colonies. On May 29, Patrick Henry rose in the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg to make a protest speech against the Stamp Act. Forewarned of the speech by Henry who stayed with Jefferson whenever Henry visited Williamsburg, Jefferson walked down Duke of Glouster Street with his friend and fellow law student, John Tyler (the father of John Tyler, Jr. our country’s future tenth President) to take in Henry’s theatrics.

Peter F. Rothermel. “Patrick Henry Before the Virginia House of Burgesses.” Wikimedia, Collection of Patrick Henry’s Red Hill.

Henry lived up to his advance billing and shocked his fellow Burgesses with his words declaring that Parliament’s usurpation of taxation authority “has a manifest tendency to destroy British as well as American freedom” and implying resistance to the measure. Cries of “Treason, Treason” filled the hall, and Henry famously replied, “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Jefferson was moved by Henry’s delivery and his message. In his autobiography, Jefferson stated the oratory was “such as I have never heard from any other man.”

More importantly, Henry’s speech planted the revolutionary seeds in Jefferson’s mind that he was an American, rather than a British subject. These seeds would germinate and be reaped in 1776 in Jefferson’s masterpiece, the Declaration of Independence.

But that was ten years in the future, and for now Jefferson settled into his life as a newly minted attorney. In colonial Virginia, there were two levels of courts, the county courts and the General Court of Virginia. The county courts were scattered throughout the colony and the attorneys practicing their art in them tended to be less educated and less sophisticated than those that practiced at the General Court in Williamsburg. Additionally, while county court attorneys were fairly numerous, in 1767 only eight lawyers practiced before the General Court.

The common practice was for new lawyers to get their experience and initial fees in the county courts and then possibly try to get admitted to the General Court, the true legal elite of Virginia. Jefferson opted to bypass the county courts and try for admittance to the General Court right away believing that it to be the only place where law as a “science may be encouraged.” He was accepted and, at age twenty four, joined a small group of attorneys much older than Jefferson and considered the best the colony had to offer, men such as George Wythe, Edmund Pendleton, Peyton Randolph, John Blair, and Richard Bland.

Being the only attorney from western Virginia practicing before the General Court, Jefferson headed west from Williamsburg looking for clients who needed a lawyer to bring their case back east to the General Court. Over the course of the next seven years, Jefferson crisscrossed the colony on horseback visiting courthouses in nearly every county, developing a broad clientele, and, more importantly, establishing a reputation as one of the most respected barristers in Virginia. Jefferson was not afraid of hard work and handled as many as five hundred cases a year, representing some of the wealthiest men in the colony.

The recognition Jefferson gained by his hard work paid dividends in 1768 when the twenty five year old Jefferson was elected to the House of Burgesses, filling the seat his revered father, Peter, had once held. Jefferson entered the assembly at a time of mounting emotions in both Virginia and the other colonies, in large part because of the Townshend Acts of 1767. These measures imposed additional taxes on the colonists and further encroached on American liberties.

There was also growing concern in the colonies about the habit of Crown officials to dissolve colonial legislatures whenever they refused to comply with Parliamentary acts with which they disagreed. The New York assembly had been dissolved in 1768 when it refused to adhere to the Quartering Act and pay to house British troops stationed in the colony. In response, the Massachusetts House sent out a circular letter calling for a united response from all colonies in support of New York; as a result, the Massachusetts House was suspended by its Royal Governor.

In May 1769, the House of Burgesses passed resolves drafted by George Washington, George Mason, and Richard Henry Lee which stated that all taxation authority rested in colonial legislatures and called for a boycott of all British goods until Parliament reversed course. Jefferson, the new Burgess from Albemarle County, took his first steps down the road to revolution when he signed these provocative resolves, aligning himself with what the Governor called the “young hotheads.”

Even though he signed, Jefferson felt the demands did not go far enough in that he believed Parliament did not have the authority to impose any taxes, internal or external, on the colonies. Lord Botetourt, the Royal Governor, angered by the resolves, immediately dissolved the Assembly. Parliament’s acts were unwittingly turning thirteen disparate British colonies into a unified American confederation. That probably would not have happened were it not for their heavy handed methods which gave the Americans a rallying point around which to coalesce.

Next week, we will discuss the radicalization of Thomas Jefferson. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.