John Adams Dominates Second Continental Congress

John Adams dominated the Second Continental Congress like no other man and was tireless in his efforts to move the assembly towards independence. He sat on ninety committees and chaired twenty-five of them. No other delegate matched his workload. Fellow Congressman Benjamin Rush told a friend “Every member of Congress in 1776 acknowledged him (Adams) to be the first man in the House.”

Importantly, John was the head of the Board of War and Ordinance, with responsibilities much like a Secretary of War. He worked with numerous Continental officers to understand the needs of the fledgling army. Adams came to realize more than any delegate how under supplied and under equipped General George Washington’s force was. He was the Continental Army’s greatest advocate.

By the fall of 1775, Adams was exhausted and returned home to Braintree for a rest and to spend time with Abigail and the children. However, duty called, and by early February 1776, Adams was back in Philadelphia anxious to convince Congress to adopt a resolution declaring our independence from England. In Adams’ opinion, the time for action had come.

J.L.G. Ferris. “Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776.”

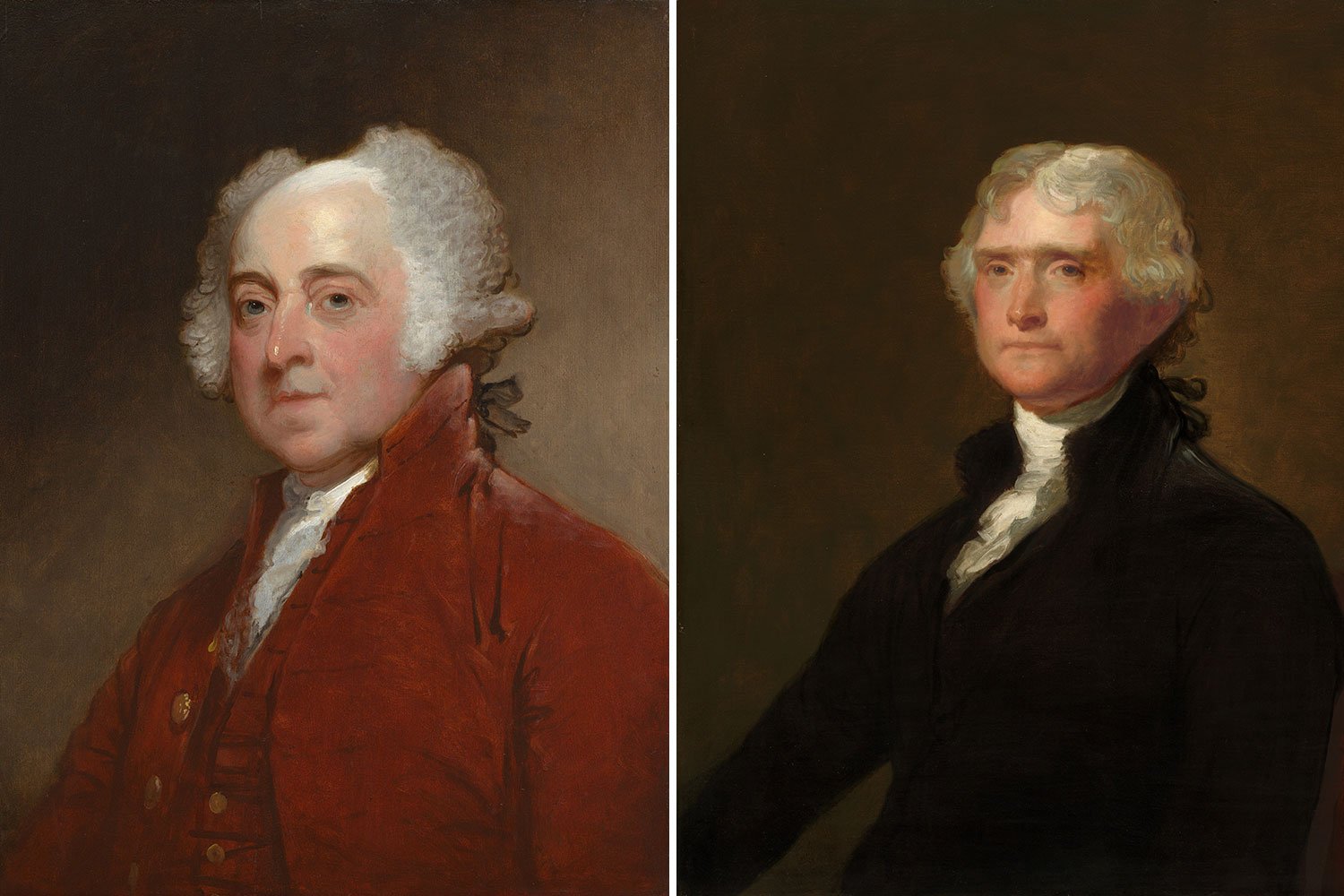

Anticipating this event, Adams organized and selected a Committee of Five to draft a statement explaining to the world why we were separating from Great Britain. This group included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson. As with his choice of Washington for Commander of the Continental Army, Adams again selected a Virginian, Jefferson, to draft the document declaring our independence.

This was an incredibly unselfish act by Adams given the importance of the declaration and the enduring fame that he knew would be assigned to its author. It is even more amazing given his great skill and experience as a writer. However, the nation always came first with Adams, and he worried that he was too polarizing of a figure to get the declaration easily approved.

The committee worked together on the final document, with Adams and Franklin acting as editors of Jefferson’s draft. They presented the Declaration to Congress on June 28 and the debate began with all delegates participating, a sort of “committee of the whole.” This larger group of editors removed all references to slavery to appease the delegations from South Carolina and Georgia and cut out roughly a quarter of the original draft.

Adams was masterful in arguments for the resolution and was able to overcome objections from more conservative members such as John Dickinson. Through sheer force of will and a supremely convincing explanation of how governments should work, Adams almost single-handedly convinced Congress to unanimously pass our Declaration of Independence. It was perhaps John Adams’ finest hour.

WHY IT MATTERS

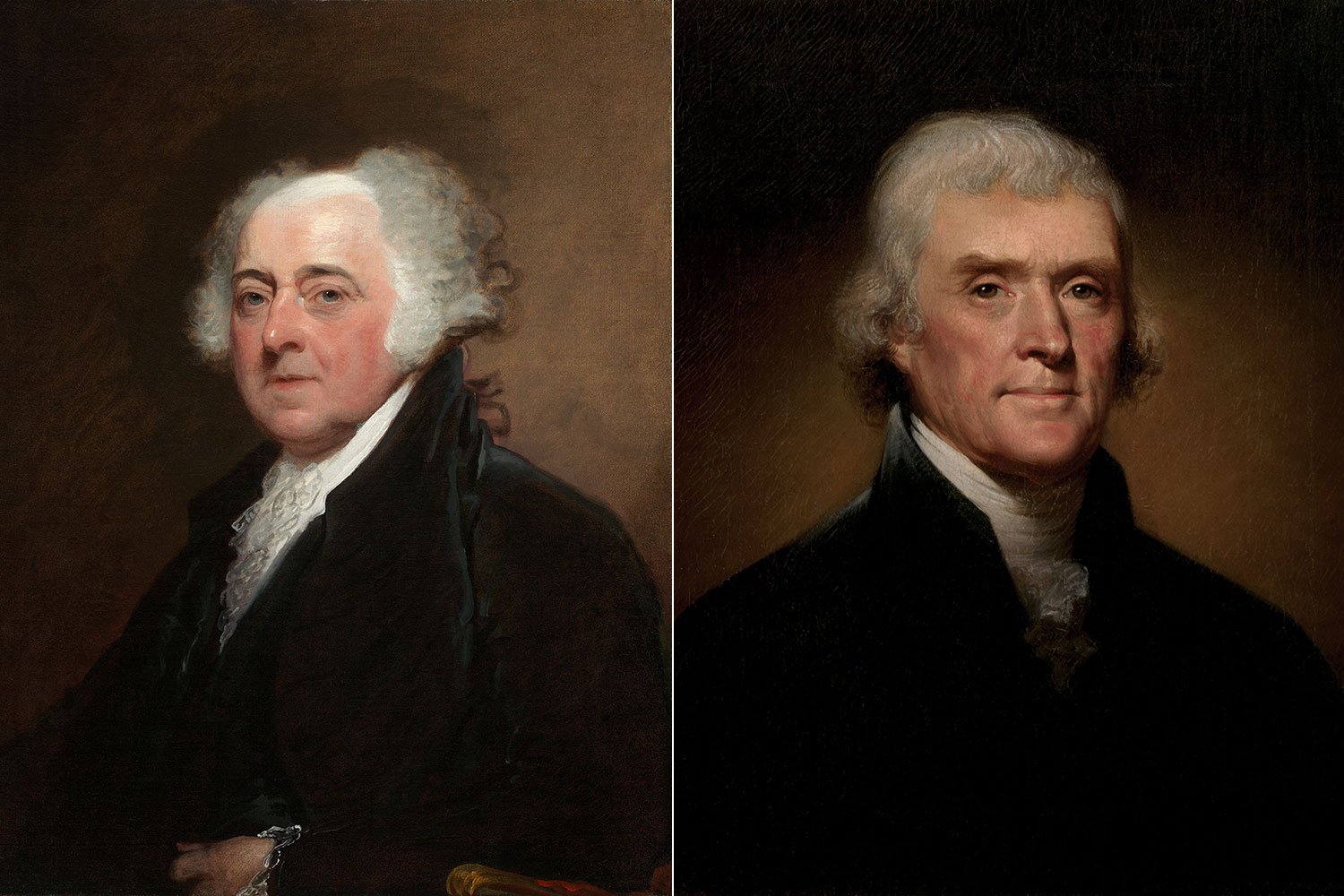

So why should John Adams’ role in the Second Continental Congress matter to us today? John Adams did many great things at the Second Continental Congress, but two stand out from all the others. First, he gave us George Washington. By nominating that great man to be the Commander of our Continental Army, Adams set Washington on the path to becoming the Father of our Country.

Second, he was instrumental in convincing Congress to unanimously pass a declaration of independence from England. Without his persuasive speeches, it is unlikely all colonies would have agreed to such a bold move. The leadership he displayed and the clarity of his words, swayed the timid to join in our glorious cause.

SUGGESTED READING

Revolutionary Summer, a book written by Joseph Ellis, is a detailed account of the historic year of 1776. Published in 2013, it examines influential figures such as George Washington and John Adams and the events that shaped our nation.

PLACES TO VISIT

Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where our Declaration of Independence was signed, is a must see for all Americans. This iconic building completed in 1753 as the Pennsylvania State House is a beautiful colonial brick structure within Independence National Historical Park. In terms of the importance of what happened there, no building in our country can compare.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.