The Second Continental Congress Convenes

The Second Continental Congress convened in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, soon after “the shot heard round the world” was fired at the battles of Lexington and Concord. None of the delegates knew it at the time, but John Adams was to dominate the proceedings for much of the next two years.

When Adams and the other American leaders met, a state of war essentially existed between England and her American colonies. Following the fight at Concord, colonial militiamen flocked to Boston to join the forces already besieging the British. By the end of May, there were about 16,000 Americans surrounding the city.

Despite the seemingly unavoidable conflict, not all delegates were of the same opinion as to what the next steps should be regarding our relationship with England. As the debate proceeded, three factions developed.

There was a camp of Loyalists who wanted to remain with England. Opposing them was a more radical group led by John Adams and his cousin Sam Adams who wanted complete independence from the Mother Country. Finally, there were those who were undecided. In fact, six colonies-Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina- had specific instructions to not support independence.

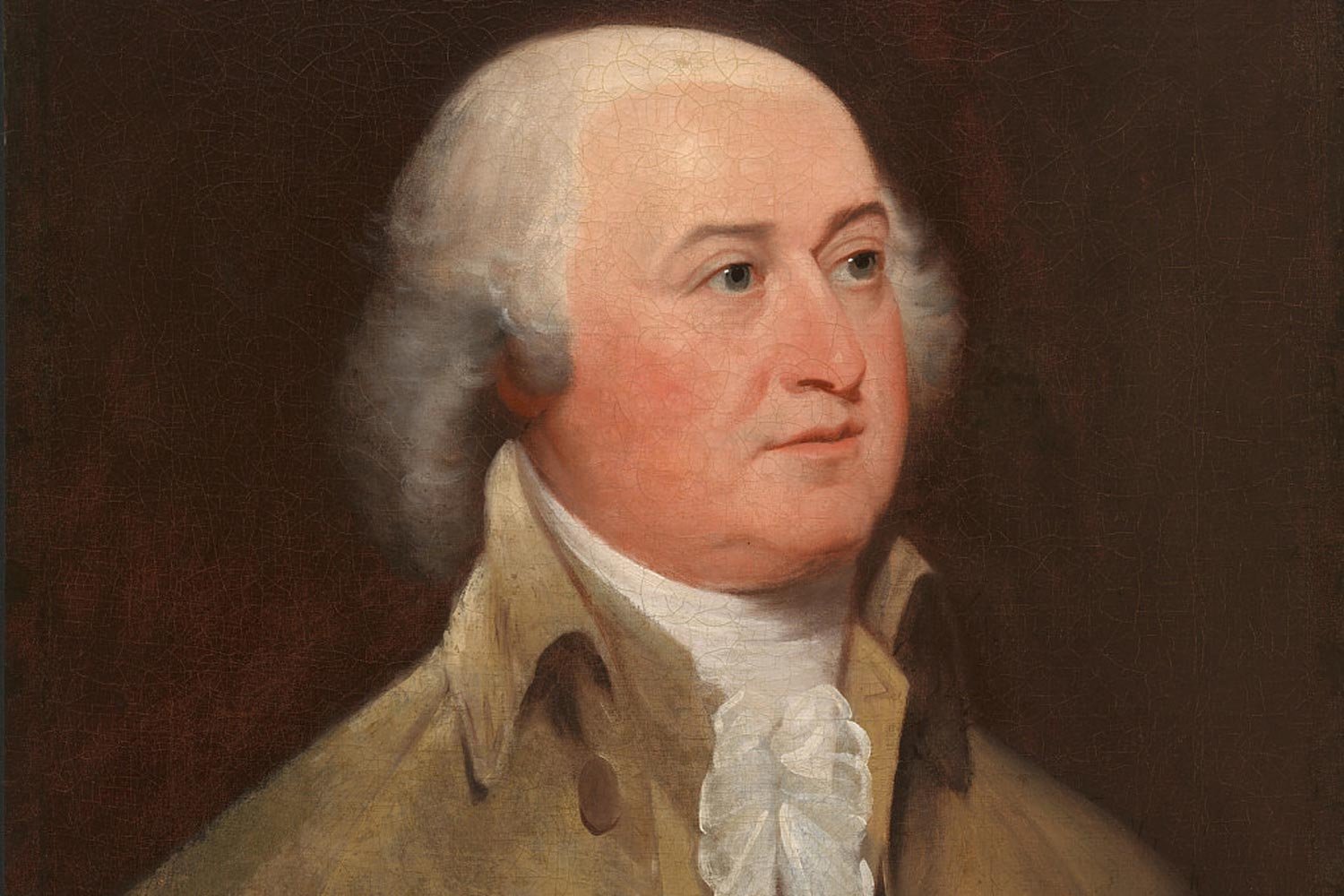

James Barton Longacre after Charles Willson Peale. “John Dickinson.”

The leader of the Loyalists was John Dickinson, a wealthy Pennsylvanian who would prove to be Adams’ greatest antagonist during the ensuing debate. Ironically, the conservative Dickinson who cautioned against separating from England had inspired many colonists to consider independence as a viable course of action.

In a series of essays Dickinson wrote in 1767-1768 entitled Letters From a Farmer in Pennsylvania, he argued that Parliament had the right to regulate colonial trade, but not taxation authority over their American colonists. Its line of reasoning was used to justify resistance to the Townshend Acts of 1767. The pamphlet was arguably the most influential one in our founding era other than Thomas Paine’s Common Sense.

In any event, Adams and the New England contingent knew they needed to get Virginia on board if they were to have any hope of convincing the other delegates to vote to separate from England. It was the most populous and affluent of the thirteen colonies and had some of British America’s most prominent citizens.

On June 14, 1775, Congress voted to form the 16,000 militiamen gathered around Boston into the Continental Army, our first national armed force. The next day, Adams wisely nominated the Virginian George Washington to be its Commander-in-Chief. This proposal was unanimously approved by the other delegates and Washington immediately headed north to Boston to begin his work.

This move to name a Virginian as the head of the Army was a bold stroke, especially considering John Hancock, the President of the Congress, and a fellow delegate from Massachusetts, wanted that post. However, Adams knew that thus far the fight for independence had largely been a New England affair.

From organizing the Stamp Act Congress in 1765 to the Boston Tea Party in 1773 to the fight at Lexington and Concord in 1775, Massachusetts had been at the center of the conflict. To make the dream of an independent and unified America a reality, Adams knew other colonies had to join the cause.

As the debate dragged on through 1775, John Dickinson and others still wanted to attempt a reconciliation with Great Britain. Adams felt war was inevitable at this point but did not strenuously argue against this effort. Consequently, on July 5, Congress adopted the Olive Branch Petition and forwarded it to King George.

This plea, this last attempt at reconciliation, claimed the colonists were loyal subjects who simply wanted more equitable trade and tax policies. It clearly stated the colonies did not want to separate from England. The petition arrived in England on August 21, but the King refused to receive it.

Instead, on August 23, King George issued the Proclamation of Rebellion declaring the American colonists to be traitors. He directed his officers to “…use their utmost endeavors to withstand and suppress such rebellion.”

Next week, we will talk about how the Second Continental Congress finally came to the decision to declare our country’s independence from England. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.