John Adams Joins the Fight for Independence

After the tragedy of the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, British troops were removed from the city of Boston and tempers cooled a bit in Massachusetts. However, Parliament soon got things heated up again when it passed the Tea Act in the spring of 1773.

That legislation allowed legally imported British East India tea to undercut the price charged by those who smuggled Dutch tea into the colonies. The problem was the British tea carried a tax and so purchasing it would imply that the colonists consented to being taxed by Parliament. It was a clever ploy, but the Americans saw through it.

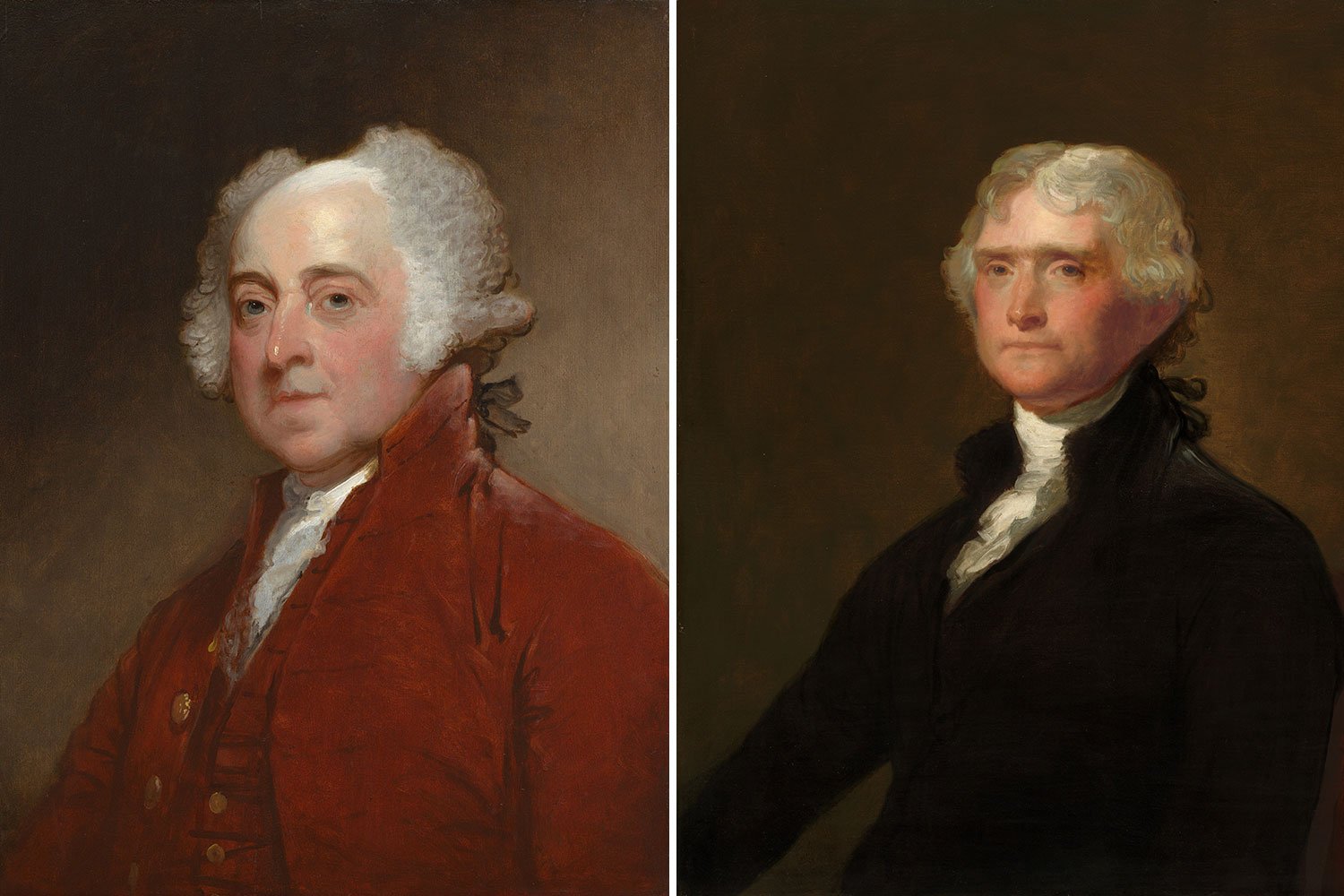

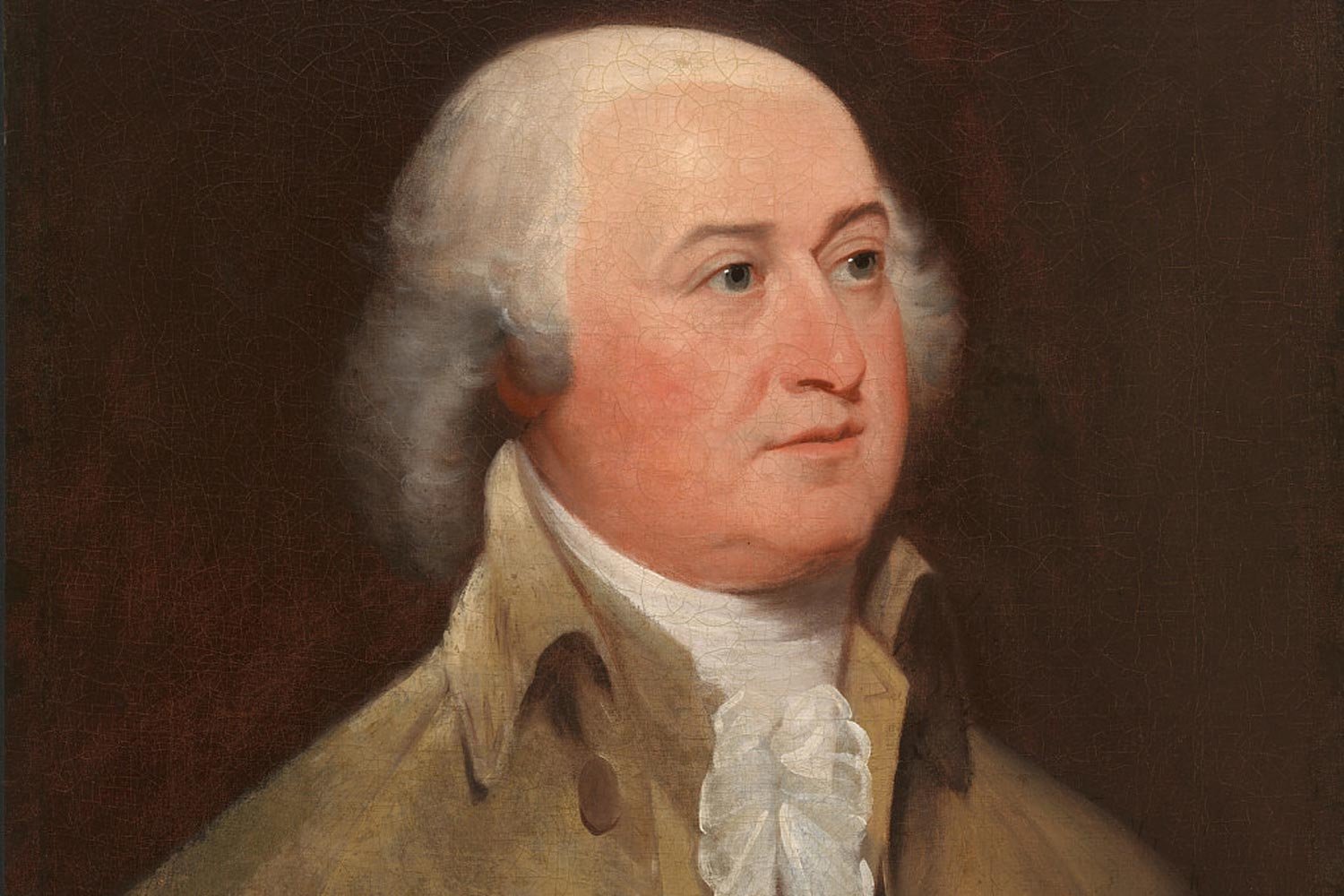

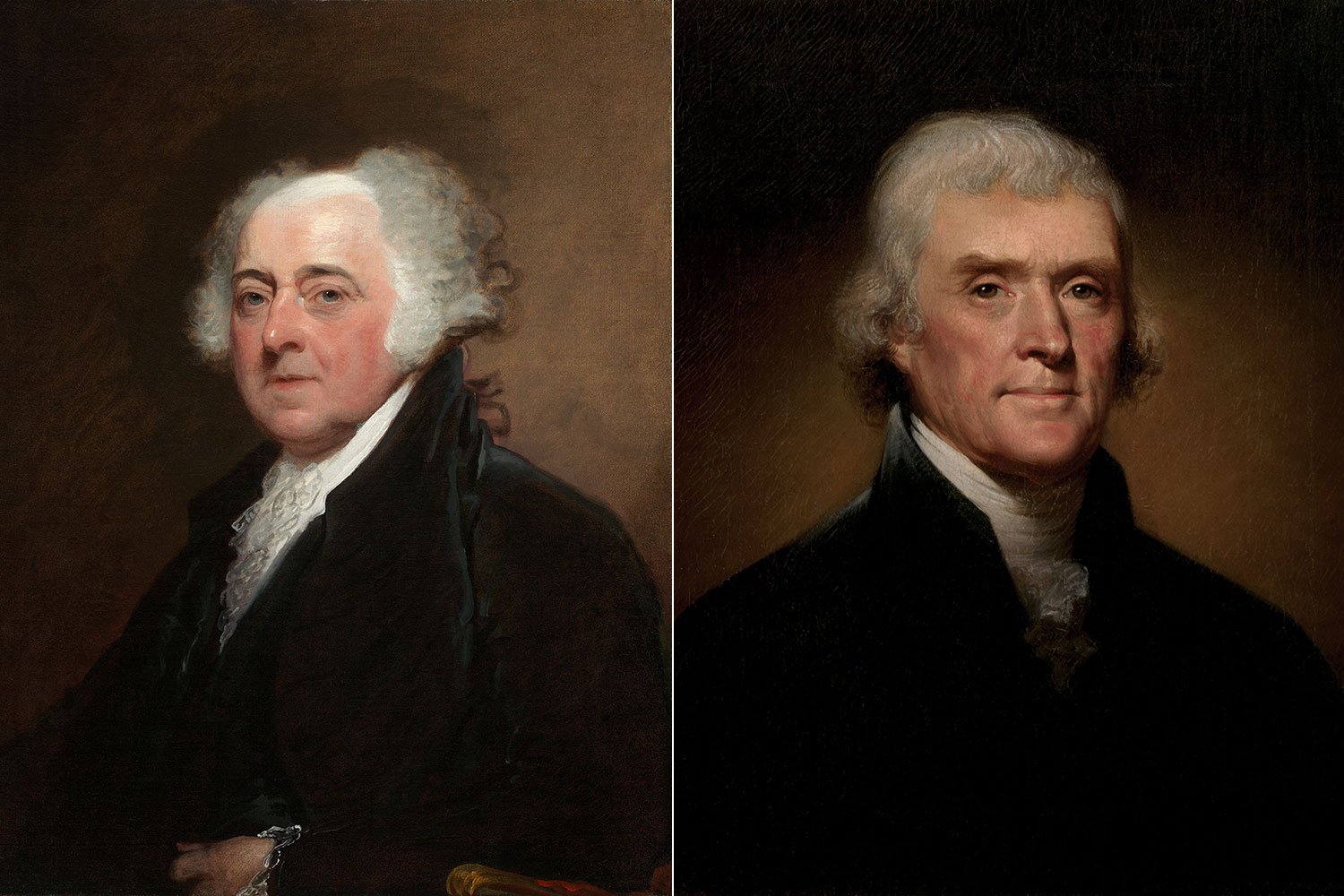

By then, John Adams had established a prosperous legal practice and was married to a fine woman with whom he had four healthy children. John led a good life and believed differences with the Crown could be and should be worked out. Sam Adams, his cousin and the leader of the Sons of Liberty, a band of colonists staunchly opposed to British taxation, felt otherwise.

Sam began to agitate against the taxes paid on British tea. Besides the “no taxation without representation” concerns, Sam was best friends with John Hancock, one of the leading smugglers of Dutch tea into the American colonies. Hancock did not want to be undercut by the legal tea, and he enlisted Sam’s support.

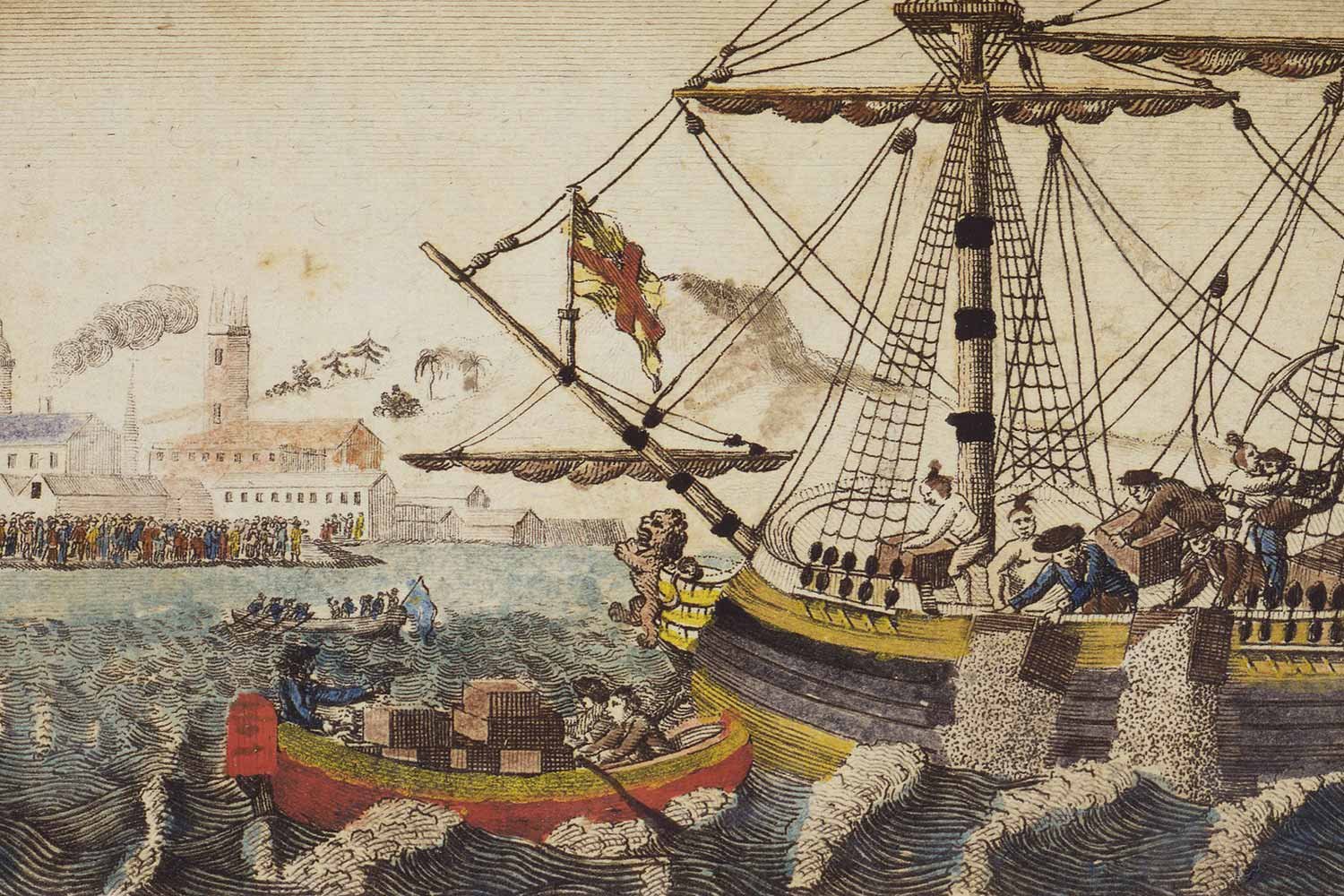

Anger against British East India tea culminated in the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. This event was anything but a party to the British as it resulted in about 92,000 pounds of tea (valued at well over $1 million in today’s money) being tossed into Boston Harbor by Sam Adams and his crew. While John Adams did not participate in the fun, he stated in a letter to James Warren that it was the “grandest event” in the revolutionary movement.

Naturally, England pushed back against this unlawful and destructive action. Just six months later, in a series of laws called the Coercive Acts (known as the Intolerable Acts in America), the British shut down the port of Boston and revoked the charter of Massachusetts. These measures placed the state under the control of the Crown.

Jacob Duché. “The First Prayer in Congress.”

As a result, colonial leaders organized the First Continental Congress in 1774 to address the growing crisis. John Adams, along with his cousin Sam and two other men, were selected to represent Massachusetts at the meeting. John, who was initially cautious in his views of American independence, had become committed to the cause.

Before leaving for this conference, Adams stated to his best friend, Jonathan Sewall, the last British Attorney General for Massachusetts, “Sink or swim, live or die, survive or perish, I am with my country…You may depend on it.” Adams subsequent actions would show truer words were never spoken.

The Delegates from twelve colonies (Georgia did not attend) assembled in Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia from September 5 to October 26, 1774. Moderates controlled the day and the dialogue at this initial effort by the colonies towards unified action. While all felt something must done to show our displeasure, exactly how far we should go was open for debate.

John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and other conservatives convinced the group that sending a petition to the King and imposing a boycott of British goods was the most prudent course to take. Importantly, the delegates voted to meet again the following year if their demands were not satisfactorily addressed.

As the events played out in this clash for the ages, planning another meeting proved to be very wise. Between the King ignoring our petition and the battles at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the next gathering, the Second Continental Congress, would prove momentous in America’s drive towards independence.

For John Adams personally, his eloquent and forceful arguments at that convention would mark one of the highlights of his illustrious career. He would dominate the discussion regarding the decision to declare our independence from England.

As Adams would point out, our decision to separate from the land of our ancestors was not made lightly or rashly. It stemmed from a long series of unfortunate decisions made by the King and Parliament.

Next week, we will talk about the opening debates of the Second Continental Congress and how the delegates viewed our deteriorating relationship with Great Britain. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.