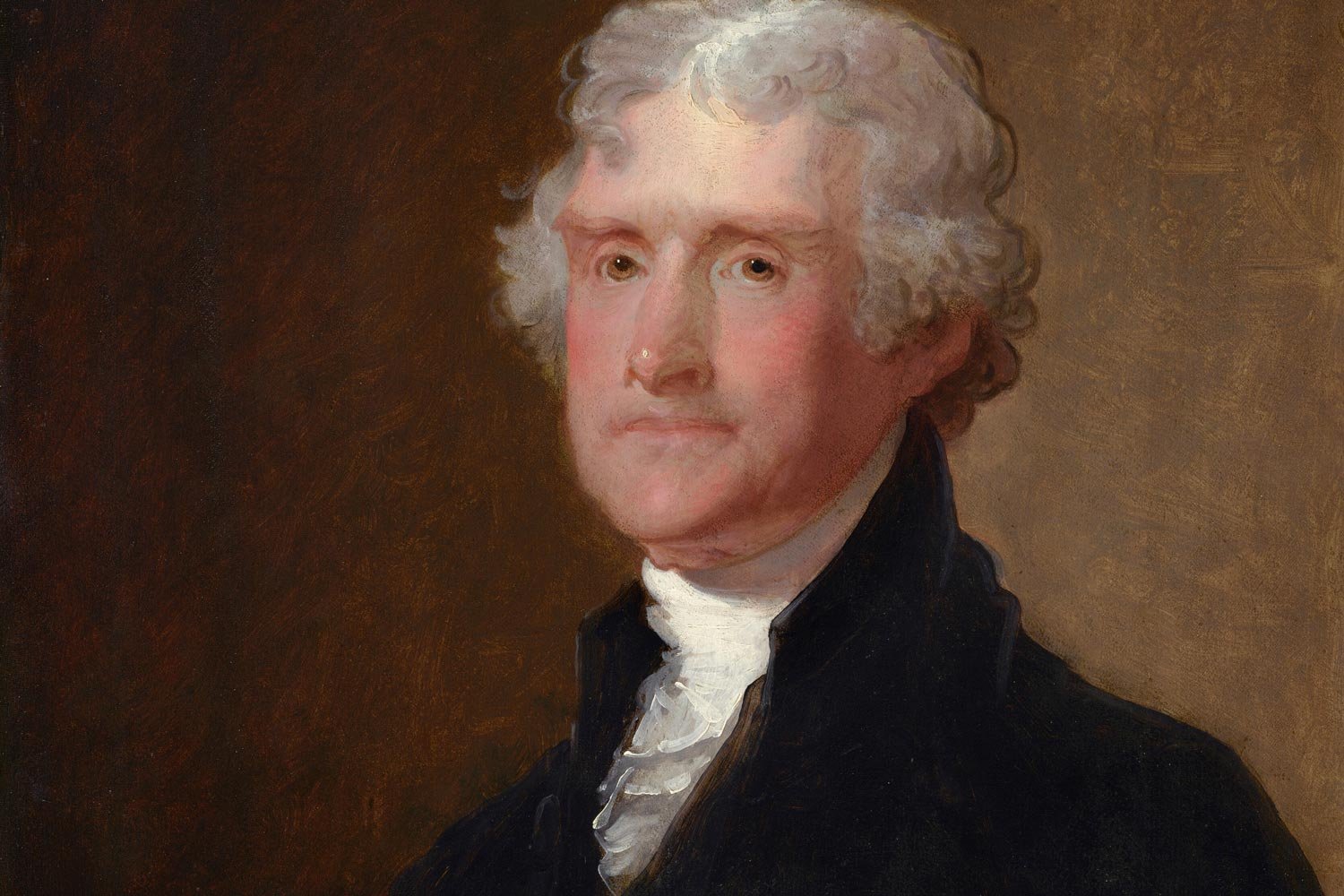

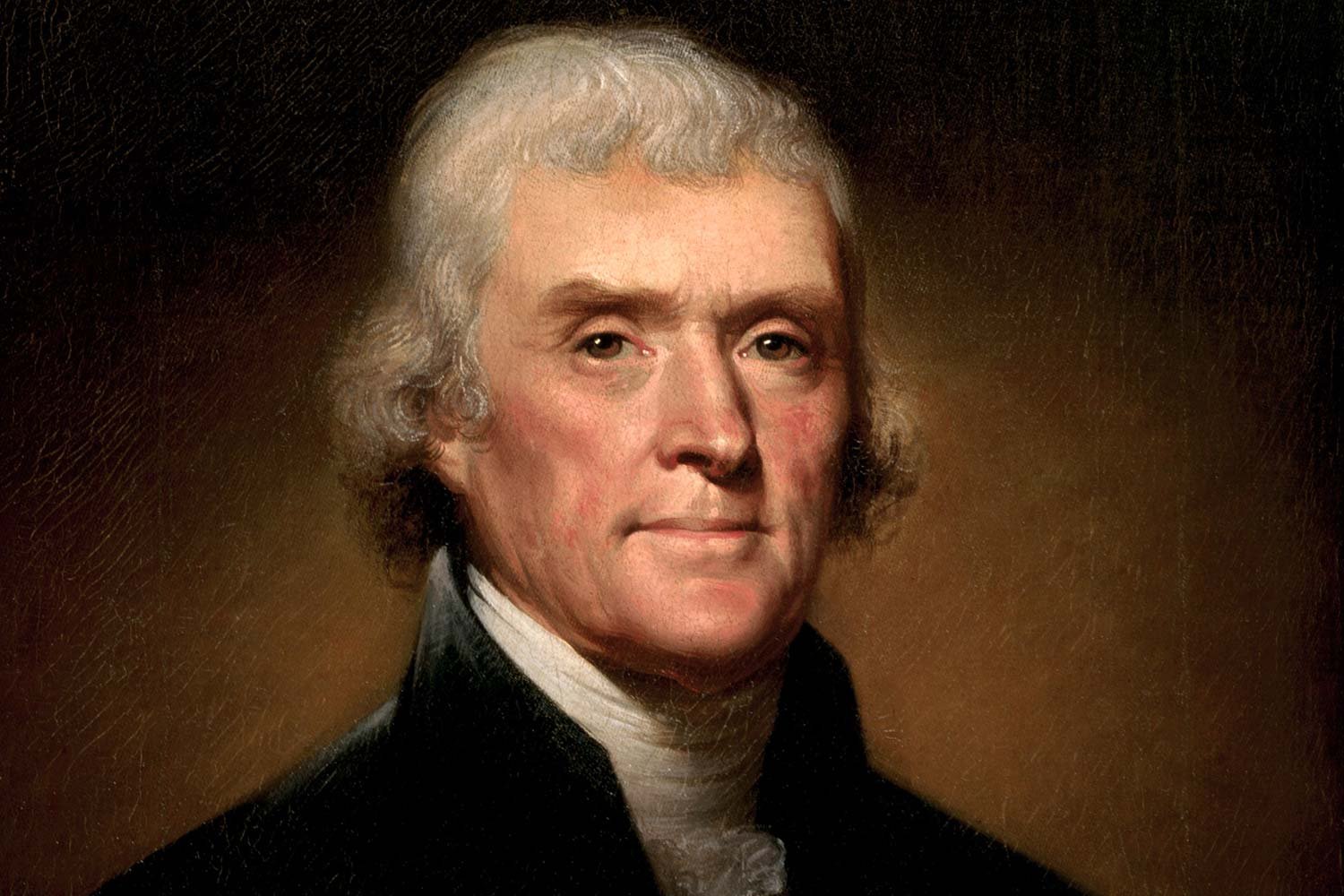

Thomas Jefferson’s “Summary View”

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.

In March 1773, Dunmore called the House of Burgesses into session for only the second time in two years. He hoped to raise taxes to renovate the College of William and Mary and to redecorate the Governor’s Mansion. But Dunmore raised a lot more than he bargained for. Prior to the opening of the session, the radical faction including Thomas Jefferson, his close friend and brother-in-law Dabney Carr, Patrick Henry, and Richard Henry Lee and his brother Francis met in secret in the Apollo Room at Raleigh Tavern. Without the Burgesses being in session for the past two years, their resistance movement against British oppression had faltered. They now saw an opportunity to resurrect it and met to discuss what resolutions they should adopt to further their cause.

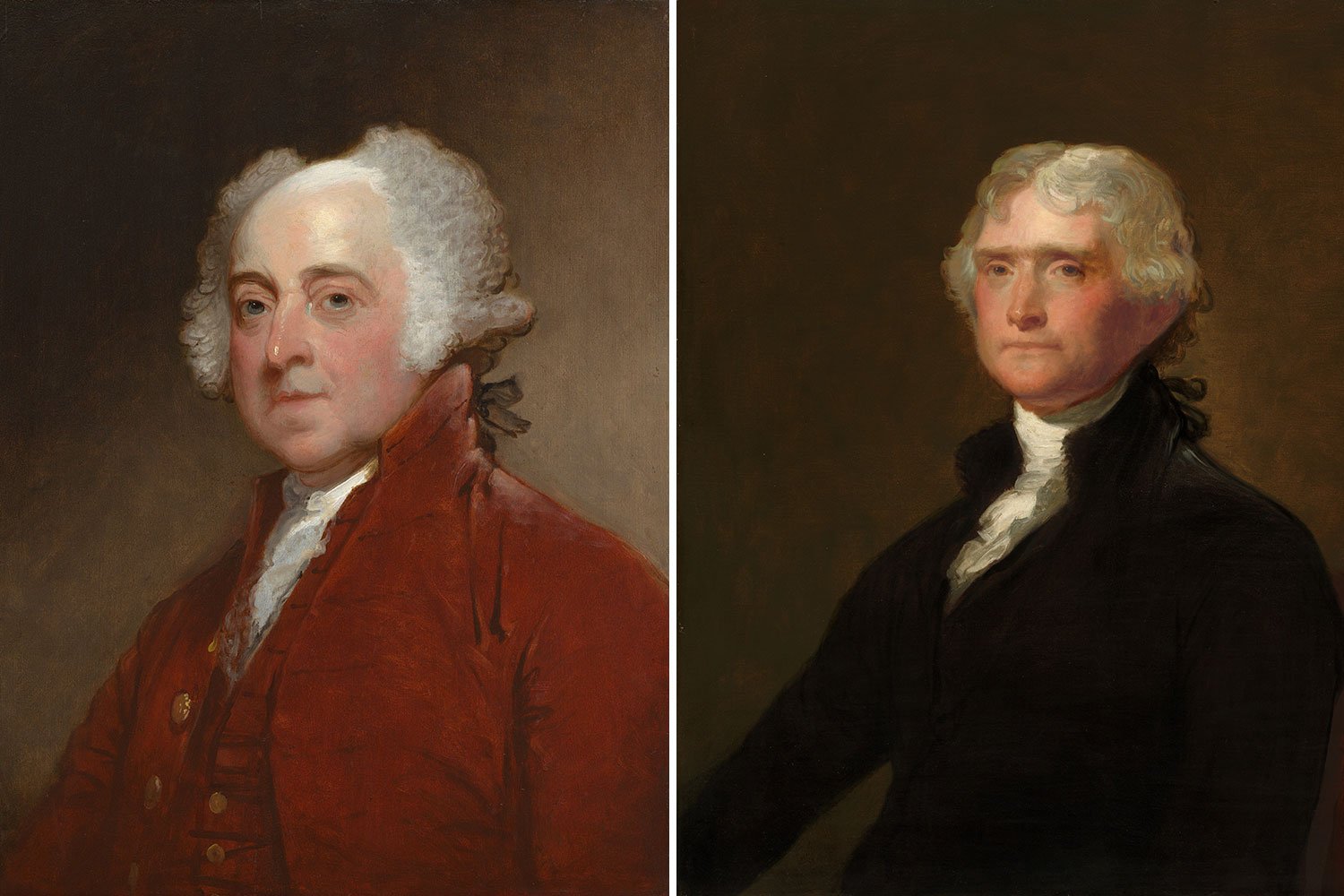

On March 12, 1773, Carr introduced a resolution written by Jefferson calling for colonial cooperation in protecting “their ancient legal and constitutional rights.” The resolution further called for setting up a standing “committee of correspondence and inquiry” to keep abreast of all Parliamentary action, the first such permanent committee in America. The resolution passed without a single dissenting vote and Jefferson’s writings were circulated to all thirteen colonies. Soon the Virginians were in regular contact with like-minded Americans such as Sam Adams and Joseph Warren in Massachusetts and John Dickinson in Pennsylvania; they were starting to think and act collectively.

By the time the Burgesses next assembled in May 1774, the revolutionary pot was coming to full boil. Parliament had passed the Tea Act in April 1773 to help prop up the struggling British East India Company. The measure allowed East India tea to be shipped to the colonies at a lower price with the hope of enticing Americans to purchase it. Since the tax on tea in the Townshend Act had never been rescinded, any purchases of this lower price tea would include a tax and thus imply approval by the colonies of Parliament’s right to tax.

This backdoor way of getting the colonies to set a bad precedent regarding taxation infuriated the Americans and led to the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, during which 94,000 pounds of British East India tea was dumped into Boston Harbor. This wanton destruction of private property could not go unpunished, and, consequently, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in early 1774 which closed the port of Boston and revoked the Charter of Massachusetts, replacing home rule with direct rule from London.

“Peyton Randolph.” Library of Congress.

Jefferson was shocked stating “This is administering justice with a heavy hand indeed” and met with his fellow radicals to draft their response. Jefferson drafted a resolution calling for a “day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer” on June 1, the day the port of Boston was to be closed. Jefferson called Great Britain’s actions “the hostile invasion” of Boston and called for “one heart and one mind firmly to oppose, by all just and proper means, every injury to American rights.”

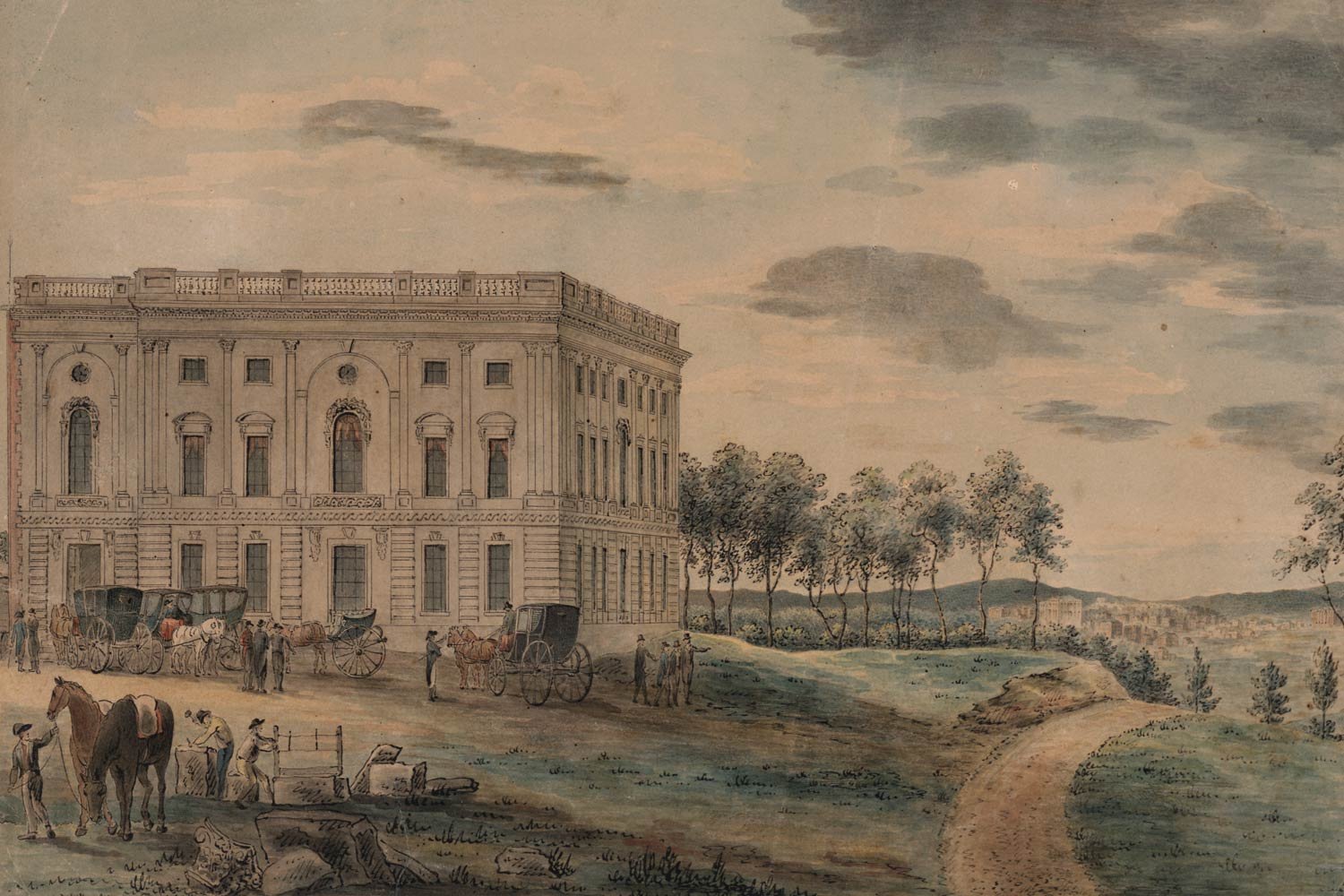

On May 26, Jefferson’s resolution, which passed without opposition, appeared in the Virginia Gazette. Later that afternoon, an angry Lord Dunmore read Jefferson’s bold statement and dissolved the assembly. The next day, the dismissed Burgesses met in Raleigh Tavern in direct violation of Dunmore’s decree. Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Peyton Randolph and others called for a permanent assembly of representatives from all the colonies to meet annually to discuss their joint response. They also organized a colony-wide meeting to be held in Williamsburg on August 1 so the Burgesses could have time to go home and get the pulse of the people on the next steps for their resistance to British authority.

Jefferson returned to Monticello, his retreat from the world, and began composing a treatise on what he saw as the proper relationship between the King, Parliament, and the colonies, and he based his reasoning on both historical precedent and the Enlightenment teachings of men like John Locke. Jefferson wrote with raw emotion and what he proposed was even too radical for the radicals.

Jefferson asserted that “Parliament had no right to exercise authority over us” and this meant no authority at all, not just regarding taxation. Jefferson denied Parliament’s right to control where we shipped our products and with which countries we traded; he denied Parliament’s right to determine which goods we could manufacture; and he further stated that the government of each colony was a “free and independent legislature” and that Parliament “could not take upon itself to suspend the powers of another.”

Jefferson also discredited the powers of the King, declaring that the King was simply an executive whose authority was relegated to meditating disputes between various groups or states within the Empire. He closed by reminding King George that the Americans were independent and warned him that they would not tolerate further encroachments on their liberty. He wrote, “These are our grievances, which we have thus laid before his majesty, with that freedom of language and sentiment which becomes a free people, claiming their rights as derived from the laws of nature, and not as a gift from their chief magistrate. Let those flatter who fear; it is not an American art.”

He worked himself to the point of exhaustion over the course of five weeks while preparing his presentation. Jefferson completed it in late July and headed for Williamsburg but only made it a short way before being forced to return due to ill health. Jefferson sent a copy of his writings to Peyton Randolph, the moderator of the first Virginia Convention, who shared it with the assemblage.

The Burgesses were shocked at the strength and even anger of Jefferson’s words and, with Jefferson not there to defend his assertions, more cautious voices moved towards a conciliatory approach. But Jefferson’s followers recognized the beauty of his words and the strength of his argument. They gave a title to his treatise, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, and circulated it across America and in England. Despite its seemingly radical nature at the time, it is one of the truly classic accounts of the American position in the lead up to the American Revolution and would prove to be where the American people netted out after Lexington and Concord.

Next week, we will discuss the growing revolutionary movement. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

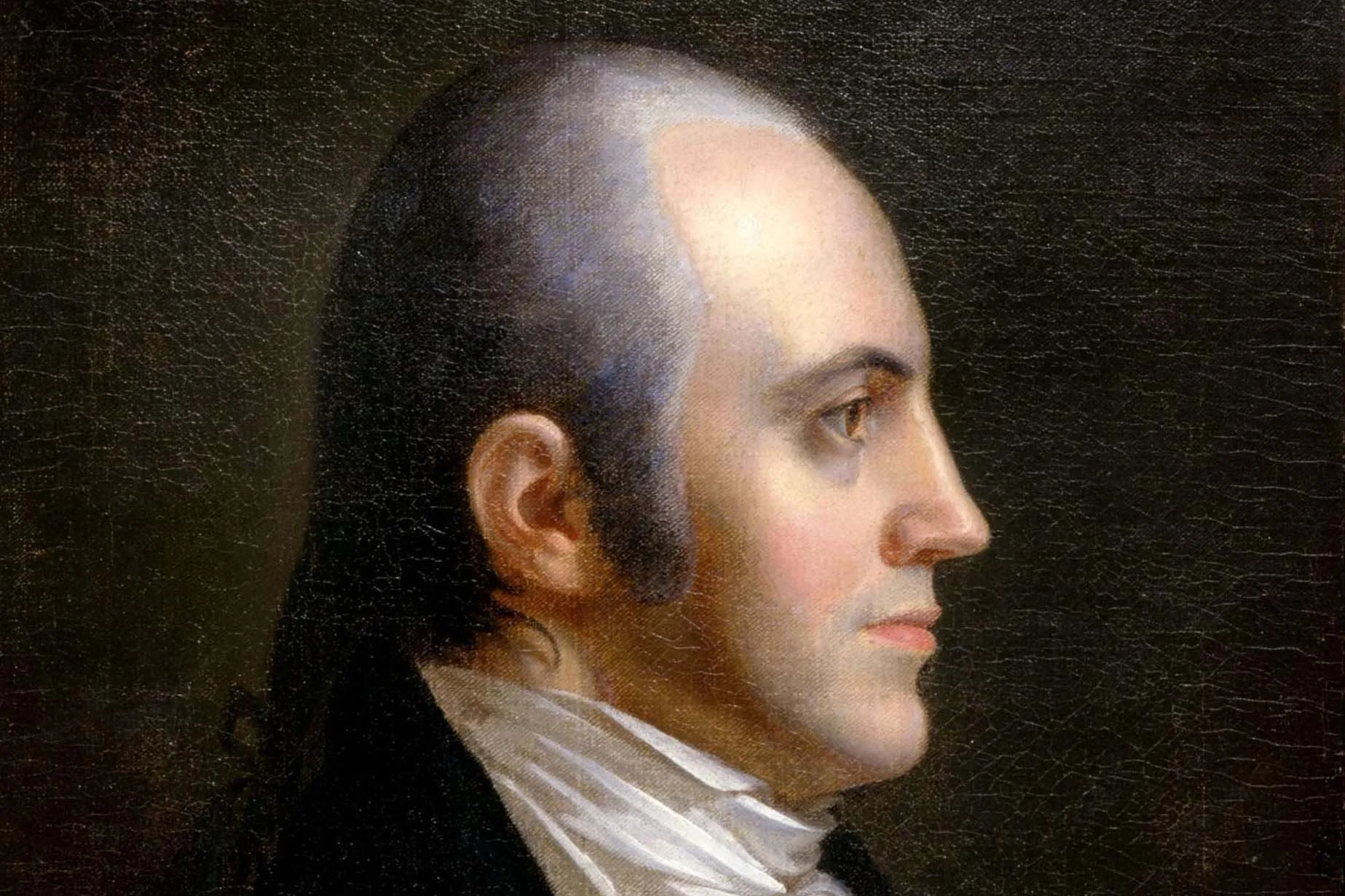

Aaron Burr's grand scheme to create his own country, possibly in Mexico or from United States territory, began to collapse late in 1806, practically before it ever got started. This empire in the sky built largely in Burr’s fertile mind was swiftly coming to an end.