The Legacy of George Washington

No man has had a greater impact on the United States than George Washington. This quintessential American carried the country through eight long years of its Revolution and devoted another eight years getting the new Constitutional government established as its first President. Washington was one of those rare individuals who seemed destined, almost from birth, for greatness, as if the hand of Divine Providence was watching over and protecting him, saving him for greater things.

In 1754, with tensions between England and France increasing, the recently promoted Colonel George Washington led a small force towards Fort Duquesne and encountered a French force. The ensuing confrontations at Jumonville Glen and Fort Necessity led to the outbreak of the French and Indian War and added to Washington’s growing fame. At the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755, as he bravely led the retreat with his commander mortally wounded, his clothing was pierced by four bullets and two horses were shot out from under him, but Washington never received a scratch.

And on that cold winter morning of January 3, 1777, in Princeton, New Jersey, Washington rode to within thirty yards of a regiment of British soldiers firing at his charging line of Continentals. Despite the sheet of bullets, Washington survived unscathed. Amazingly, in all the engagements throughout his life, Washington was never wounded, and yet he was a man who led from the front with unflinching bravery.

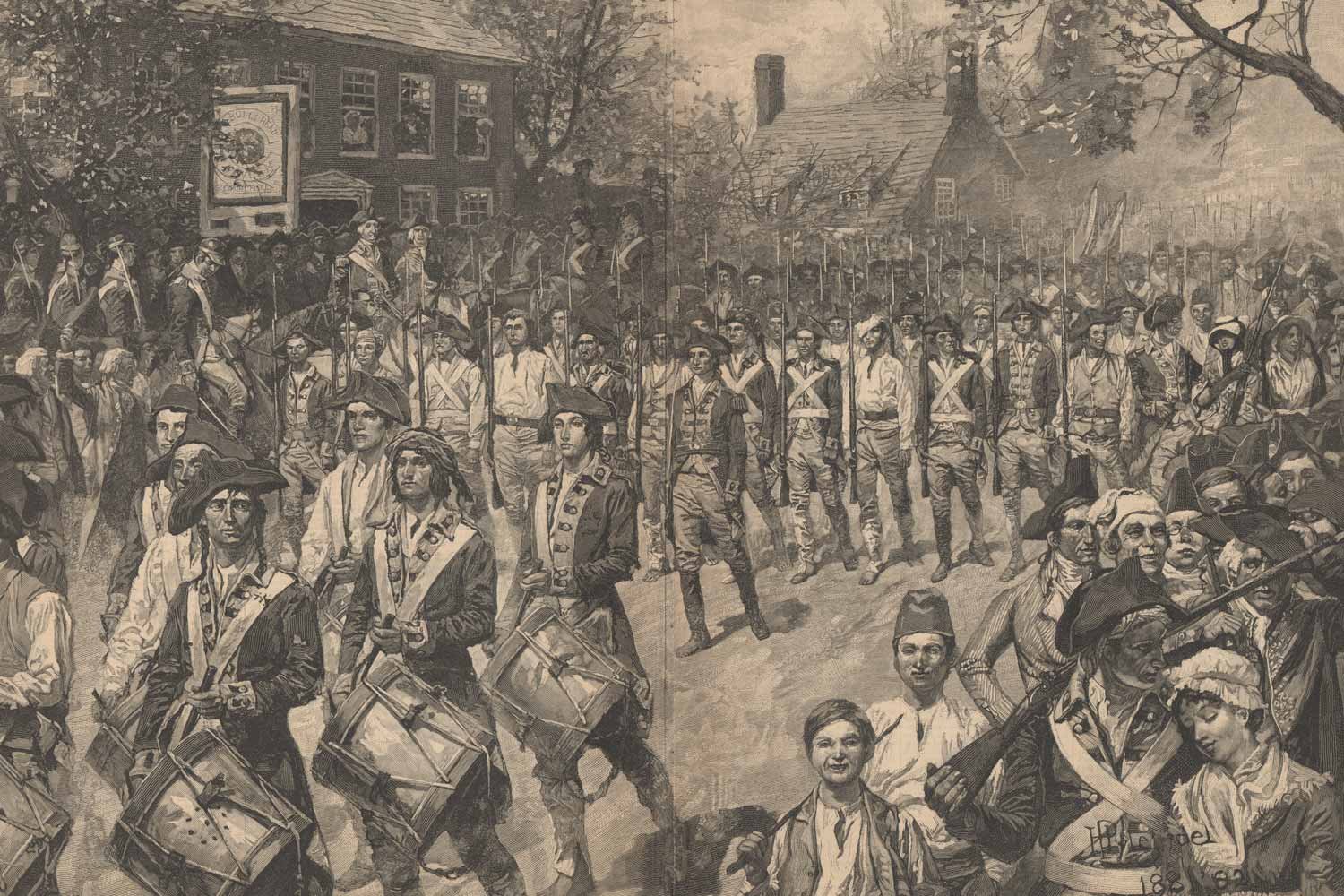

William T. Ranney. "Washington Rallying the Americans at the Battle of Princeton, 1848." Princeton University Art Museum.

Washington was remarkable in so many ways, but perhaps none so much as his willingness to surrender power. Washington lived in a time when men held onto their authority until their dying breath, but he shocked the world when, at the end of the American Revolution and with an adoring army ready to follow him anywhere, he voluntarily resigned his commission to the Confederation Congress. Even King George III exclaimed this unselfish act made him “the greatest man in the world.”

With this resignation, Washington was announcing to his fellow citizens, as well as to the rest of the world, the supremacy of civilian authority over the military in the United States of America. This was a new concept in a new world.

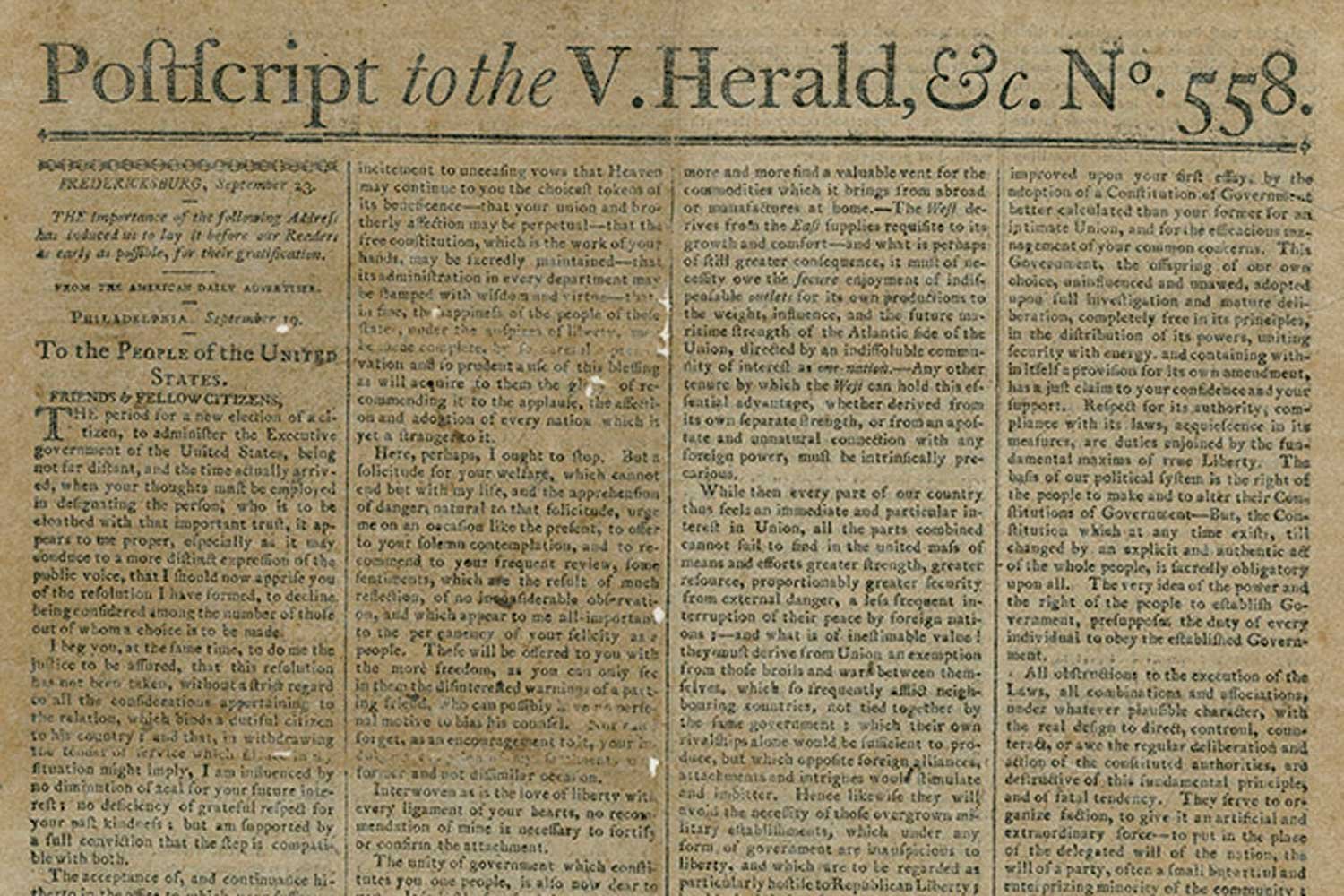

In 1796, after serving two terms as the nation’s President, Washington could easily have served a third if he desired, but he declined. Here was a man who could have remained President for life; no one would have denied him the honor and the Constitution did not forbid it.

Instead, aware that everything he did would affect posterity, Washington wisely chose to step down and transfer power to John Adams, his duly elected successor. He thereby established the precedent that the Presidency was not a lifetime position. He understood that power can corrupt, especially when held onto for too long, and the nation was more important than any one man.

This voluntary transfer of power is taken for granted today, but peacefully relinquishing power was not something leaders of countries did in the eighteenth century. All Washington and his contemporaries had ever known was lifetime hereditary rule. No European monarch had ever done what President Washington did on March 4, 1797, and that truly revolutionary act deserves to be remembered.

When George Washington died on December 14, 1799, the entire country fell into a state of mourning, fearful of how it would survive without their bedrock leader. No one, before or since, has been so universally revered and admired.

At Washington’s funeral, Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, his trusted cavalry officer from the American Revolution, gave a eulogy in which he accurately stated the sentiments of the nation: Washington was “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Besides the gift of a stable country, Washington left posterity an intangible blessing, a timeless national hero. During America’s war for independence, General Washington was the one man who was above reproach. He was a good husband and family man; he managed his private affairs with great skill, never being scandalized or leaving his character open to criticism.

He was brave and fearless almost to a fault and he suffered alongside his men on every campaign and in every encampment. The empathy he felt for the men in the ranks was discernible by all, and for that he was adored by his soldiers.

As President, he came under more severe scrutiny and unflattering criticism, but Washington always remained above the fray. Despite wounded feelings at uncalled for attacks on his decisions and even his character, Washington did not lash out or seek to embarrass anyone in the public forum. Washington was unfailingly Presidential.

Washington continues to be the indispensable man all Americans can look to for inspiration, and his writings, especially his Farewell Address, provide enduring guidance for the country. Many Founding Fathers, and others since, have left their impact on America and helped make it a better place. But Washington’s legacy to the United States is truly supreme as without his guiding hand it is doubtful the country could have been created.

Next week, we will discuss the election of 1796. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

No man has had a greater impact on the United States than George Washington. This quintessential American carried the country through eight long years of its Revolution and devoted another eight years getting the new Constitutional government established as its first President. Washington was one of those rare individuals who seemed destined, almost from birth, for greatness, as if the hand of Divine Providence was watching over and protecting him, saving him for greater things.