Washington’s Farewell Address – The Background

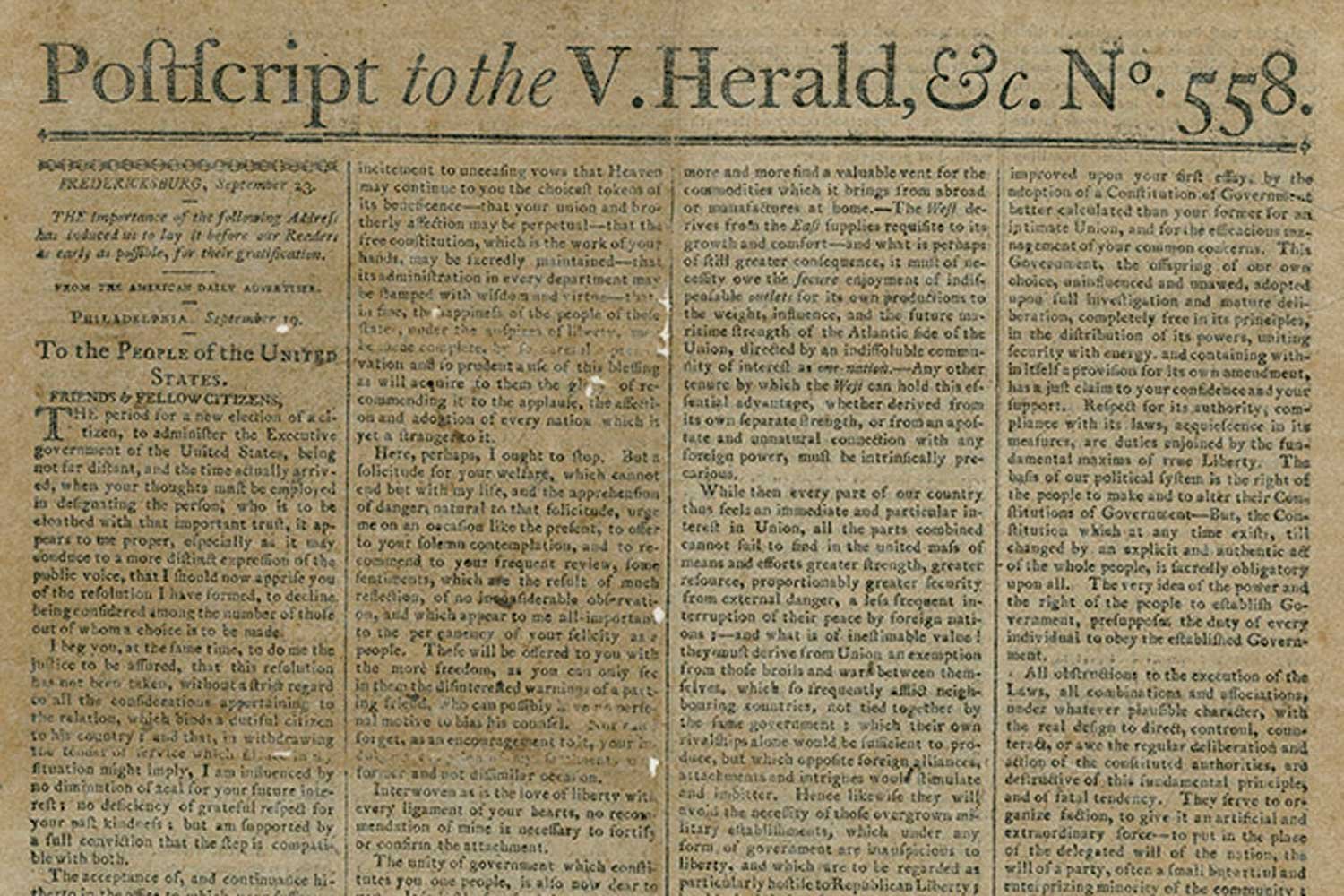

George Washington’s Farewell Address is one of the greatest documents in our nation’s history. It was a letter written by President Washington to his fellow citizens as he neared the end of his second term as President. Published in the American Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1796, its purpose was to inform Washington’s countrymen that he would not seek a third term as chief executive and provide the reasons why, as well as give some fatherly advice for America moving forward.

As President Washington approached the end of his second term, he was ready to retire from public life and return to his beloved estate, Mount Vernon, to spend more time with Martha and their extended family. This was not the first time he felt this way. Four years earlier, as he neared the end of his first term in 1792, Washington wanted to step down and asked James Madison to draft a letter announcing this intention.

However, the President was concerned about the growing rift between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. These two key subordinates seemed to be always at odds and Washington was apprehensive of where their disagreements might lead. Despite Washington’s efforts, his fears would be realized in a few years when these two Patriots with opposing visions for the country formally divided and formed their own political parties, the first ones in America.

He also worried about increasingly strained relations between the United States and European nations, especially England and France. Washington felt, as did many others, that without his leadership internal bickering would split the nation apart and perhaps push it into the arms of a foreign power or at least embroil the United States in their affairs. This potential situation was one the President wanted to avoid at all costs, and, consequently, Washington agreed to serve another four years.

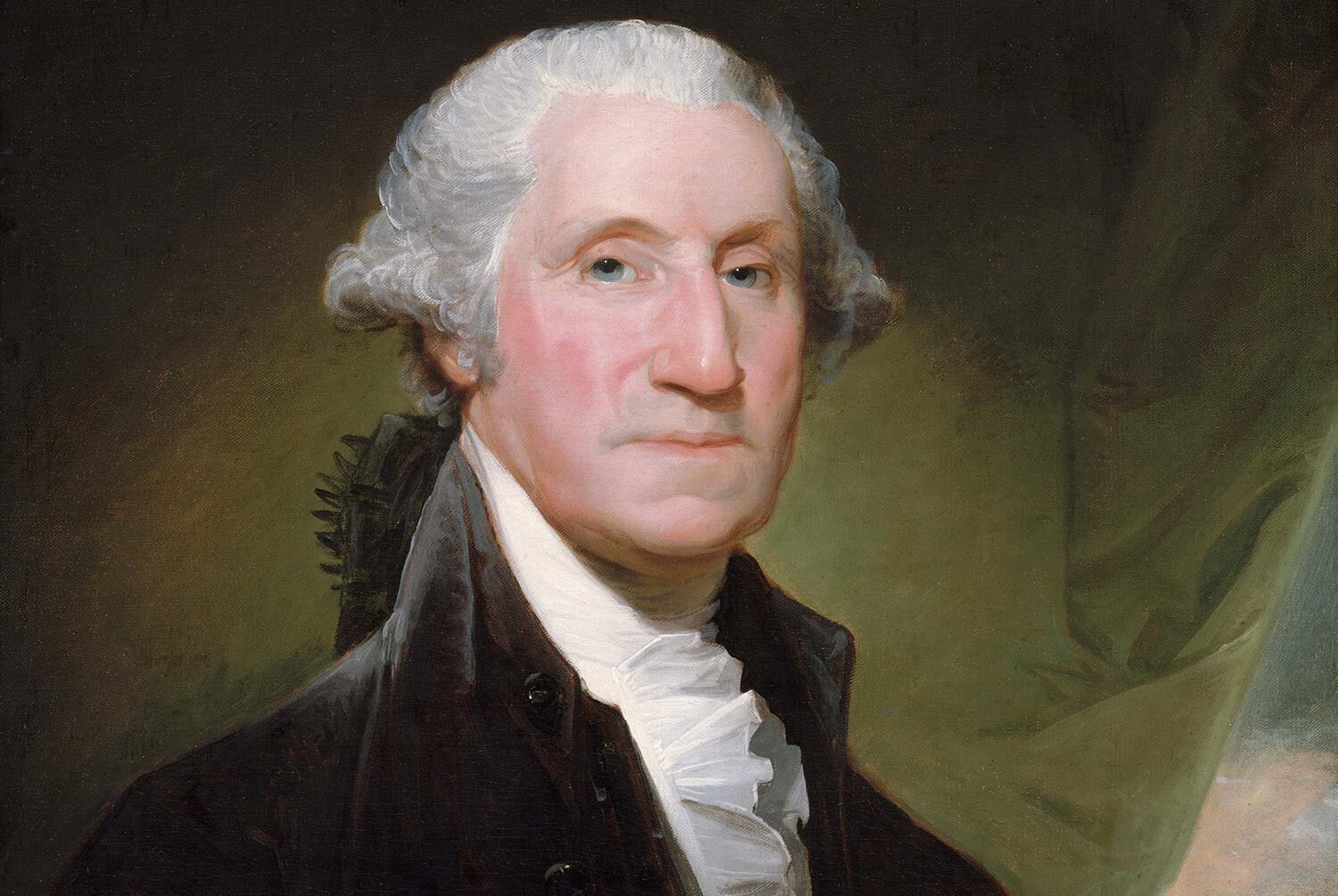

In 1796, with his second term drawing to a close, Washington would not be dissuaded from his determination to retire from public life, and this decision was primarily based on two concerns. First, quite simply he was no longer a young man and he longed to be home. Born on February 22, 1732, Washington would be sixty-five years old by the start of his third term. While not terribly old by today’s standards, it was in the eighteenth century, and Washington was mentally and physically tired.

Washington was also a bit angered, and perhaps somewhat saddened, by the harsh rhetoric aimed at him by Jeffersonians in their newspaper The National Gazette, as well as Benjamin Franklin Bache’s Aurora. At a cabinet meeting following the posting of a particularly venomous attack by Jefferson’s paper, Washington “defied any man on earth to produce one single act of his since he had been in the government which was not done on the purest of motives” and that he “had rather be on his farm than to be made the emperor of the world.”

Others were troubled by the disrespect shown to the President. Patrick Henry wrote, “If he whose character as our leader during the whole war…is so roughly handled in his old age, what may be expected of men of the common standard?”

Moreover, Washington had spent most of his adult life in the service of his country, away from his home and loved ones. From May 1775, when Washington left to attend the Second Continental Congress, until he returned home after the American Revolution on December 24, 1783, General Washington spent only ten days at Mount Vernon.

Additionally, from April 1789, when George Washington left Mount Vernon to become President, until he returned home at the end of his second term in March 1797, Washington spent only 367 days at his beautiful estate on the banks of the Potomac.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe. "A view on Mount Vernon with the Washington family on the terrace." Wikimedia.

Secondly, Washington wanted to step down from power rather than die in office. He had the foresight to recognize that many of his actions were precedent-setting and felt it was important to avoid establishing one that implied the President was a life-long appointment, much like a monarchy.

Today, Americans probably do not fully appreciate the magnitude of this decision, nor the incredible uniqueness of it. However, in the 1700s, rulers of countries simply did not surrender their position. Kings, czars, popes, and emperors all died in office, but not George Washington.

Much like when this great man voluntarily resigned his commission as commander of the Continental Army in 1783, Washington gave up the power of the presidency because he knew it was the right thing to do for the country.

It is also important to recognize the sacrifices Washington made throughout his life to help his country prosper. Washington’s willingness to do what needed to be done, to do his duty, set an example for all Americans to follow.

It is also important to appreciate the uniqueness of Washington’s decision to surrender power and its lasting impact on the country. Imagine the countless political issues and the turmoil America would have experienced if Washington had turned the presidency into a sort of elected monarchy.

An America in which the occupant of the White House could not be removed except by death or overthrow is frightening to consider. Only the genius and impeccable character of Washington prevented that from becoming a reality.

Next week, we will continue our discussion of Washington’s Farewell Address. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

No man has had a greater impact on the United States than George Washington. This quintessential American carried the country through eight long years of its Revolution and devoted another eight years getting the new Constitutional government established as its first President. Washington was one of those rare individuals who seemed destined, almost from birth, for greatness, as if the hand of Divine Providence was watching over and protecting him, saving him for greater things.