Aftermath of the Newburgh Conspiracy

The Newburgh Conspiracy represents a time when our nation came closest to deviating from our core revolutionary principles of representative government with civilian control of the military. Because of a weak Confederation Congress and unhappiness within the officer ranks of the Continental Army, the stage was set for our new nation to drift into a military dictatorship or monarchy.

Only General George Washington’s steady and unselfish leadership on March 15, 1783, when he calmed the discontent of his men, prevented that devastating outcome from occurring. Had another man been in Washington’s position, it is easy to imagine a very different ending to the Newburgh Conspiracy.

The aftermath of the crisis was that Congress, on March 20, 1783, finally did pass legislation to pay the officers a lump sum payment of five years pay instead of half pay for life. The officers wisely accepted this compromise offer, recognizing that Congress would probably struggle to pay annual pension annuities given the precarious state of the federal budget. Accordingly, they were issued government bonds that at the time were very speculative and many officers, desperate for money, sold the bonds at a deep discount. Ultimately, the bonds were fully redeemed by the new constitutional government in 1790.

While this legislation took care of the officers, it did not address the needs of the enlisted men, veterans who were not held in particularly high regard by Congress. Although the Continental Congress was quick to provide pensions to soldiers disabled in the war, service pensions were a much more contentious issue.

In lobbying for their own service pensions, enlisted men faced a series of obstacles, mainly the widespread view that a pension was a giveaway or patronage. Consequently, veterans’ advocates avoided using the word ‘pension,’ instead emphasizing that veterans were only seeking back pay. Since the government had stopped issuing pay to soldiers in 1777 as the value of the Continental (paper currency issued to help fund the American Revolution) was rapidly declining, veterans could legitimately claim that they had not received the pay that had been promised them.

Unfortunately, Revolutionary War veterans constituted a small proportion of the electorate, so they were not able to organize a powerful lobby. It was not until 1818, with the backing of President James Monroe, a Revolutionary War veteran himself, that Congress finally passed pension legislation for needy enlisted veterans.

General Washington declared an end to hostilities with England on April 19, 1783, exactly eight years after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Congress soon thereafter ordered Washington to begin furloughing the troops and disbanding the army, except for a small garrison at West Point and some posts in the northwest. In November 1783, the Continental Army that had won America’s independence from England was officially disbanded.

Currier & Ives. “Washington, appointed Commander in Chief.” Library of Congress.

The following month, General Washington traveled to Annapolis, where the Confederation Congress was meeting, and resigned his commission on December 23, 1783. This act of selflessness and his voluntary surrender of power to civilian authority was viewed with admiration and shock throughout Europe. That a man who could be king would resist the temptation was beyond the comprehension of most observers.

In the summer of 1787, the so-called “nationalists,” led by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, finally got their wishes for a stronger central government with the creation of our new Constitution. To bring home their points regarding the need for this new form of government, these two men, along with John Jay, penned the greatest of all writings on a constitutional government, The Federalist Papers.

Their new Constitution called for a stronger chief executive, one capable of leading the country in both war and peace. Naturally, this task fell to the indispensable man, George Washington, who was sworn in as the first President of the United States on April 30, 1789, further justifying the title accorded to him by his fellow citizens, Father of our Country.

So why should the Newburgh Conspiracy and General Washington’s actions to thwart it matter to us today? In 1783, George Washington was held in higher esteem by his fellow citizens than anyone in America. Moreover, he commanded the Continental Army and had the full respect and devotion of both the officers and the men in the ranks.

Washington lived at a time when military leaders did not voluntarily surrender power and contemporaries needed to look no further back than to Oliver Cromwell in the mid-1600s to see how men clung tenaciously to power. Fortunately for the country, Washington was that rare exception.

Washington’s decision to uphold the tone and tenor of the revolutionary principles and place ultimate authority in our civilian leaders rather than the military set an example for others to follow. While the Continental Army’s successes on the battlefields defeated the British Army, it could be argued that one of General Washington’s greatest victories happened in Newburgh on March 15, 1783.

Next week, we will discuss General Washington resigning his commission. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

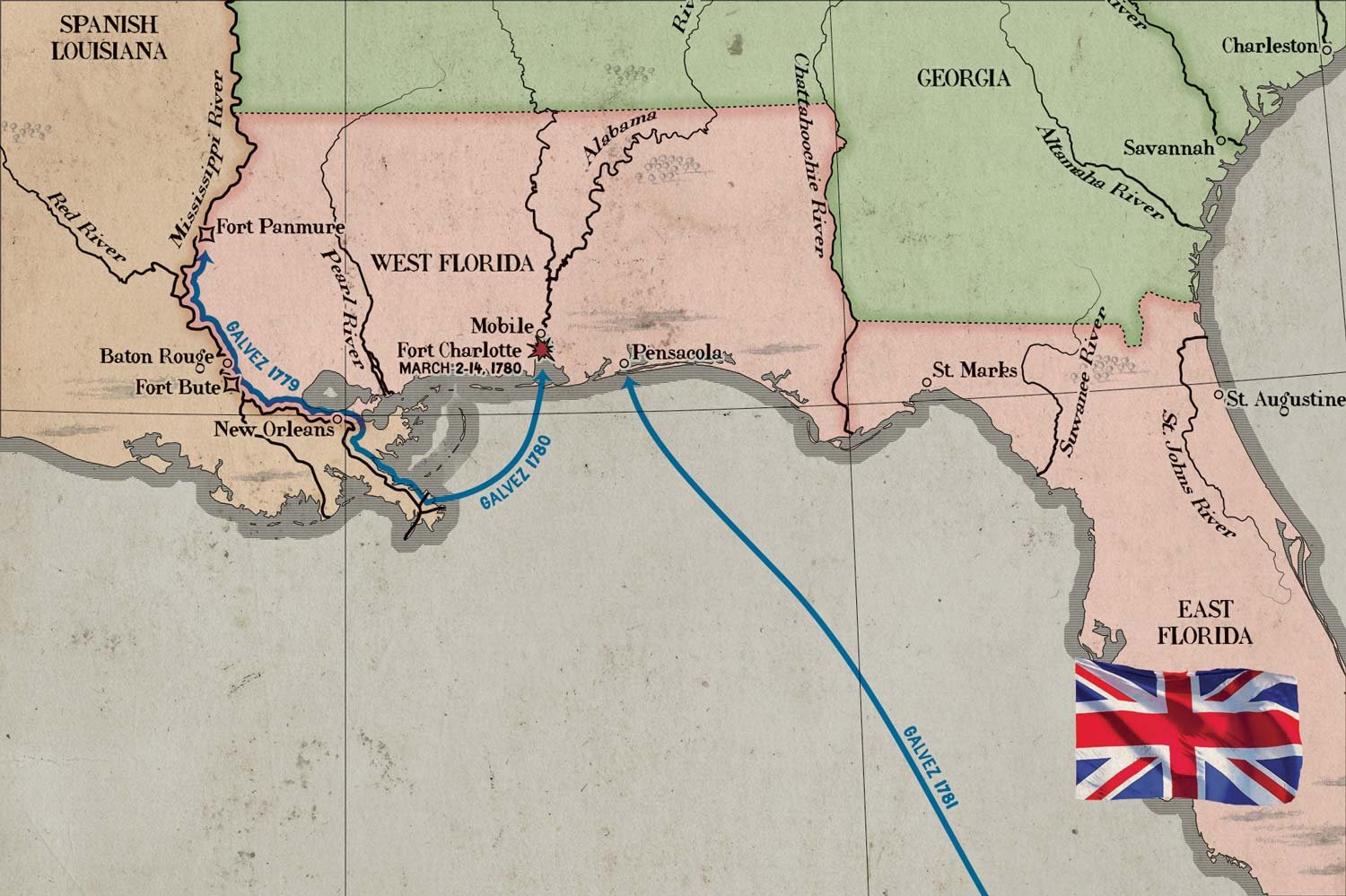

General George Washington led his Continental Army and the French Army under General Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau into Virginia in mid-September 1781. The combined force was on its way to Yorktown and its appointment with destiny with the entrapped British command of General Lord Charles Cornwallis.