America’s Founding Era, A Time of Political Unity

During America’s founding era, our country was more politically unified than at any other time in our nation’s history. That is not to say politicians did not squabble because they did. The unity was reflected in the lack of political parties at first and then essentially having only one party for a quarter of a century.

From the First Continental Congress in the fall of 1774 when representatives initially gathered to push back against England until the election of 1824 when the dominant Democratic-Republican party splintered apart, this first fifty years of America was relatively unified in its politics.

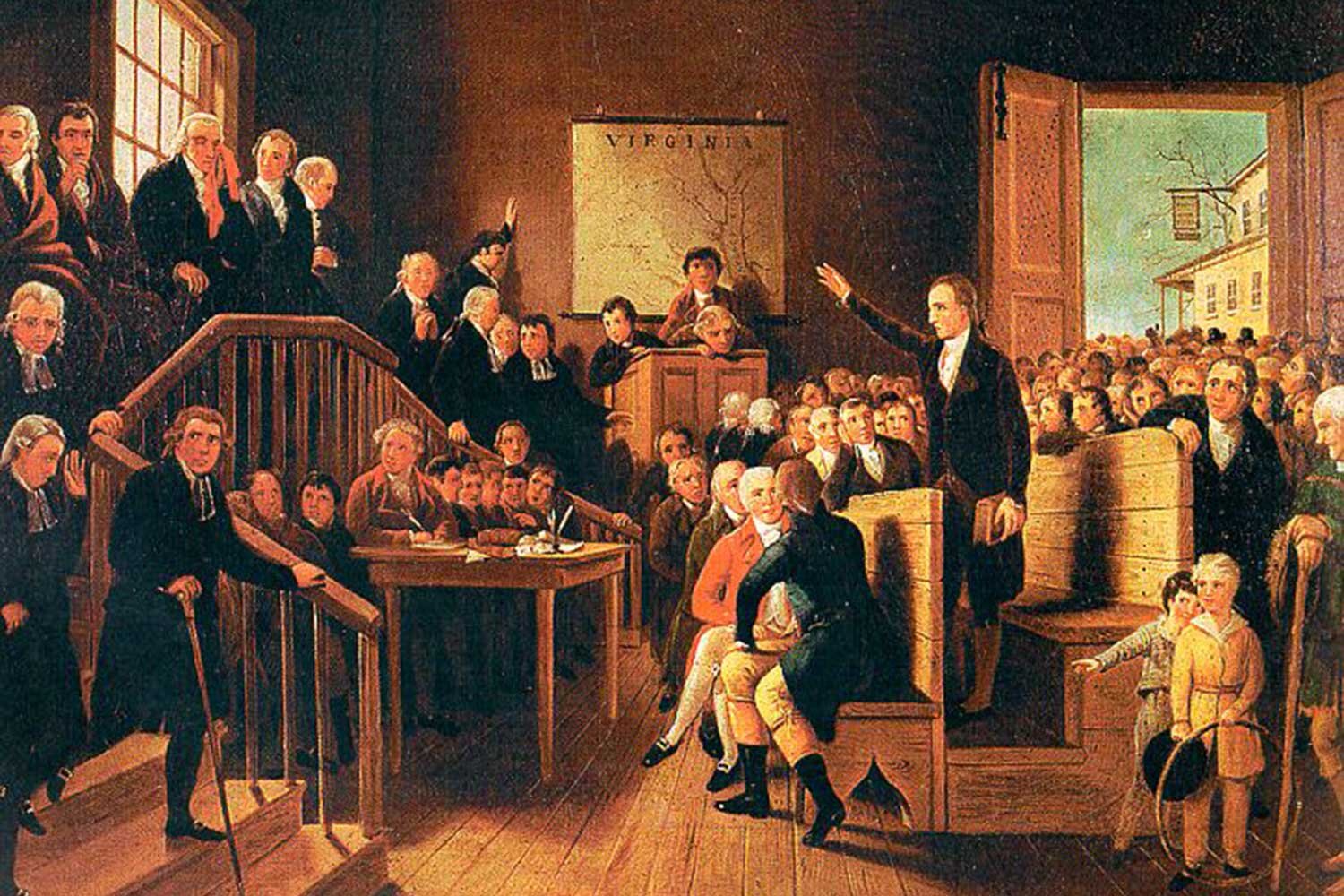

The delegates sent to the First and Second Continental Congresses from 1774-1781 were not members of any political party. These men were individually chosen based on their abilities by state assemblies that had been elected by the eligible voters in each state.

There were differences of opinion to be sure. Men like John Dickinson of Pennsylvania wanted to reconcile with England and even refused to sign our Declaration of Independence. Others such as John Adams called for a complete separation from England.

However, no one considered forming a separate political party. In essence, the Founders considered themselves all part of the American Party, fighting for a common goal, our independence from England.

When the Articles of Confederation went into effect on March 1, 1781, creating the Congress of the Confederation, nothing substantially changed from the two Continental Congresses except for the name. Despite conflicting views on the way forward, no one talked of splitting off and forming their own political party.

After a few years, it became clear the Articles of Confederation, with their emphasis on states’ rights and a weak central government, were not adequate to allow the country to survive and thrive. Consequently, in 1787, our leaders created the Constitution, issuing in a stronger federal government.

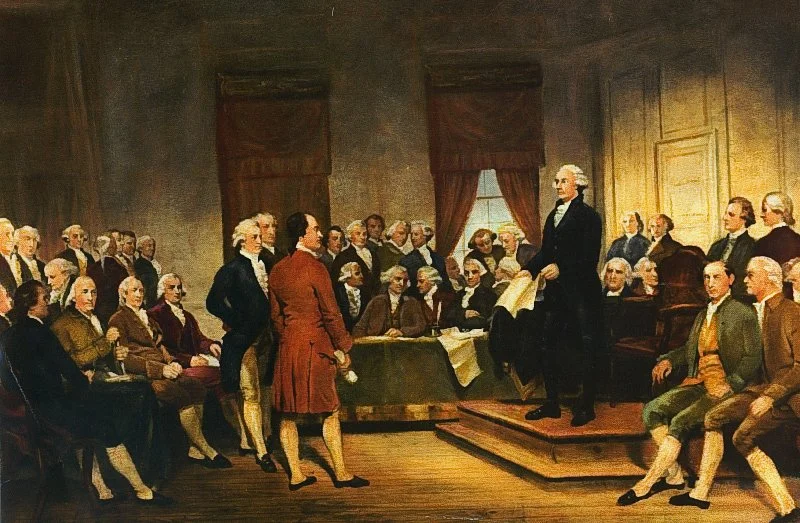

Junius Brutus Stearns. “Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention.” Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Moving forward, states would have less control over life within their boundaries, as the powerful central government imposed additional rules on the states. Virginia and the southern states would now be influenced more than ever by the wishes of New England states like Massachusetts and vice versa.

The effects of this power-sharing between the states and the central government worried many leaders. James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, warned about the development of “factions,” groups that would place their specific state or regional concerns ahead of the nation. In an essay Madison wrote known as Federalist No. 10, he explained the danger these parties/factions posed to our great experiment in democracy.

When George Washington became President in 1789 under this new Constitutional government, there were still no political parties. Those that agreed with his policies in Congress were simply called “pro-Administration” while those who were opposed were labeled “anti-Administration.”

In forming his cabinet, President Washington tried to create diversity of thought and include leaders with opposing views. He named Alexander Hamilton as his Secretary of Treasury and Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State even though the two men did not see eye to eye on most matters.

While Hamilton favored a more powerful central government and closer ties to England, Jefferson and his followers strongly believed in states’ rights and Revolutionary France. Things quickly turned sour between Hamilton and Jefferson leading to the creation of our first political parties.

Because Washington’s administration favored a stronger federal government, its supporters started to be referred to as Federalists. In 1791, Jefferson, while he was still working for President Washington as Secretary of State, helped create and fund a newspaper called the National Gazette that was critical of Washington’s administration.

Two years later, Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State to devote more time to his own political movement, the new Democratic-Republican party. By 1793-94, Democratic-Republican Societies had formed and the two voting blocs in Congress, Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, started to solidify. President Washington was quick to denounce the growing partisanship but to no avail.

In 1795, the Jay Treaty, which improved relations with Great Britain, was the spark that brought disagreements between Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans and Hamilton’s Federalist party to a boil. President Washington remained above the fray and did not participate in the growing partisan fight.

Next week, we will talk about how our first political parties formed and developed in our nation’s first century. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

There has been only one instance in our nation’s history of a United States Supreme Court Justice being impeached, and that occurred in 1804 during a significant political tussle over the independence and power of the judiciary. The justice in question was Samuel Chase and his alleged crimes seem trivial in retrospect, but Chase was simply a pawn in an ongoing battle of wills between two American icons, President Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall that took place in the early 1800s. And the decision reached in his case would have a profound impact on the future of the country.