John Adams, A Diplomat in Europe

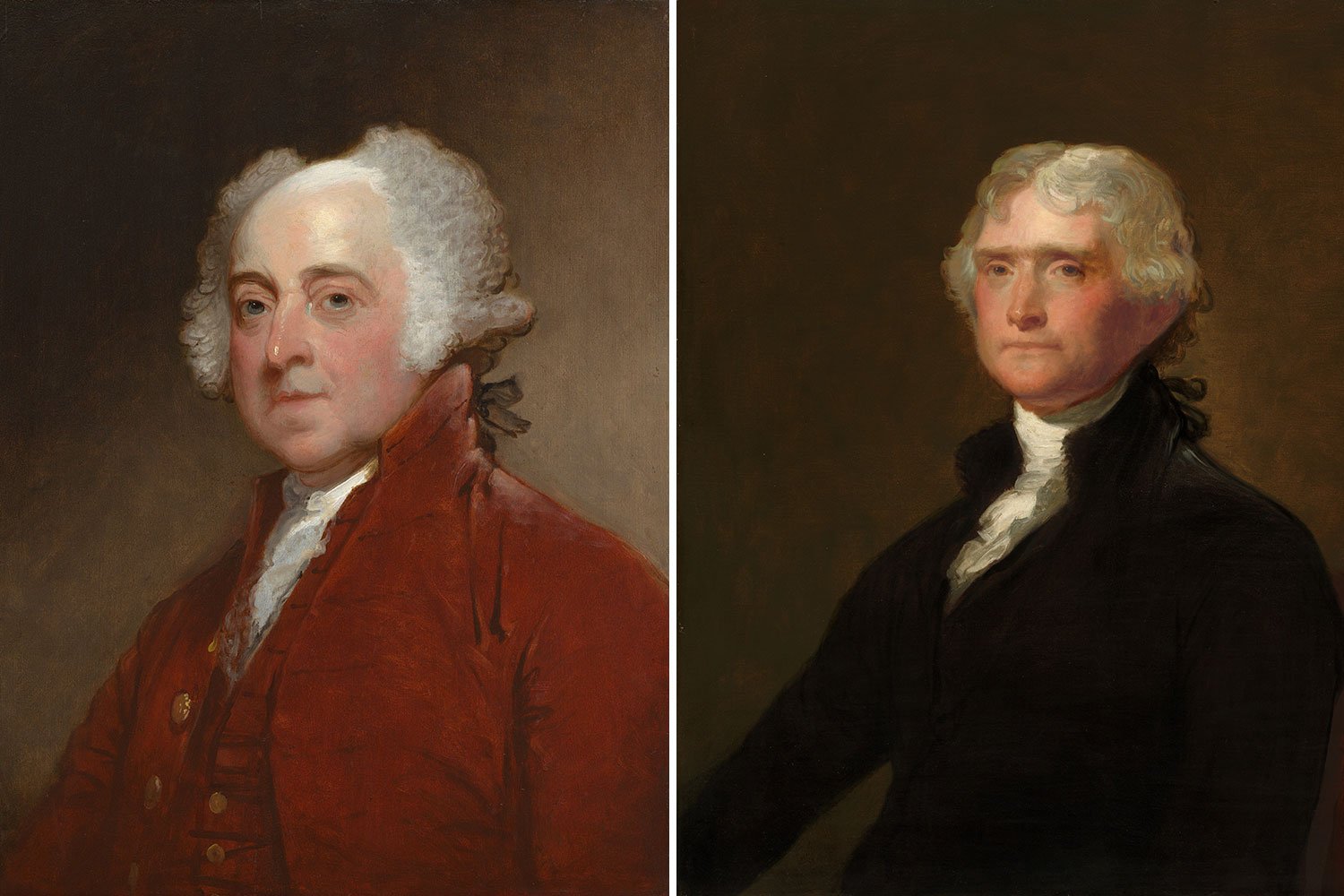

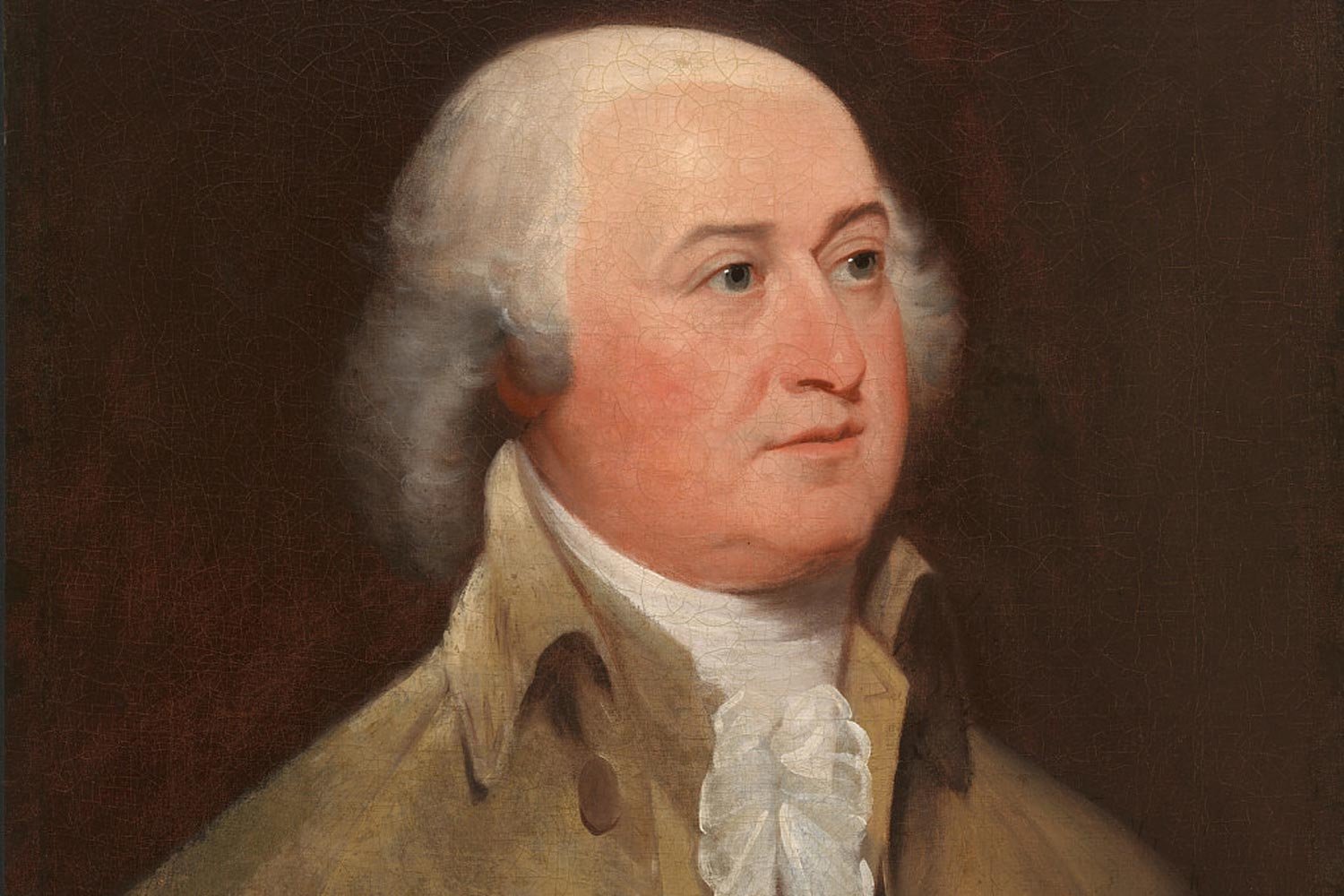

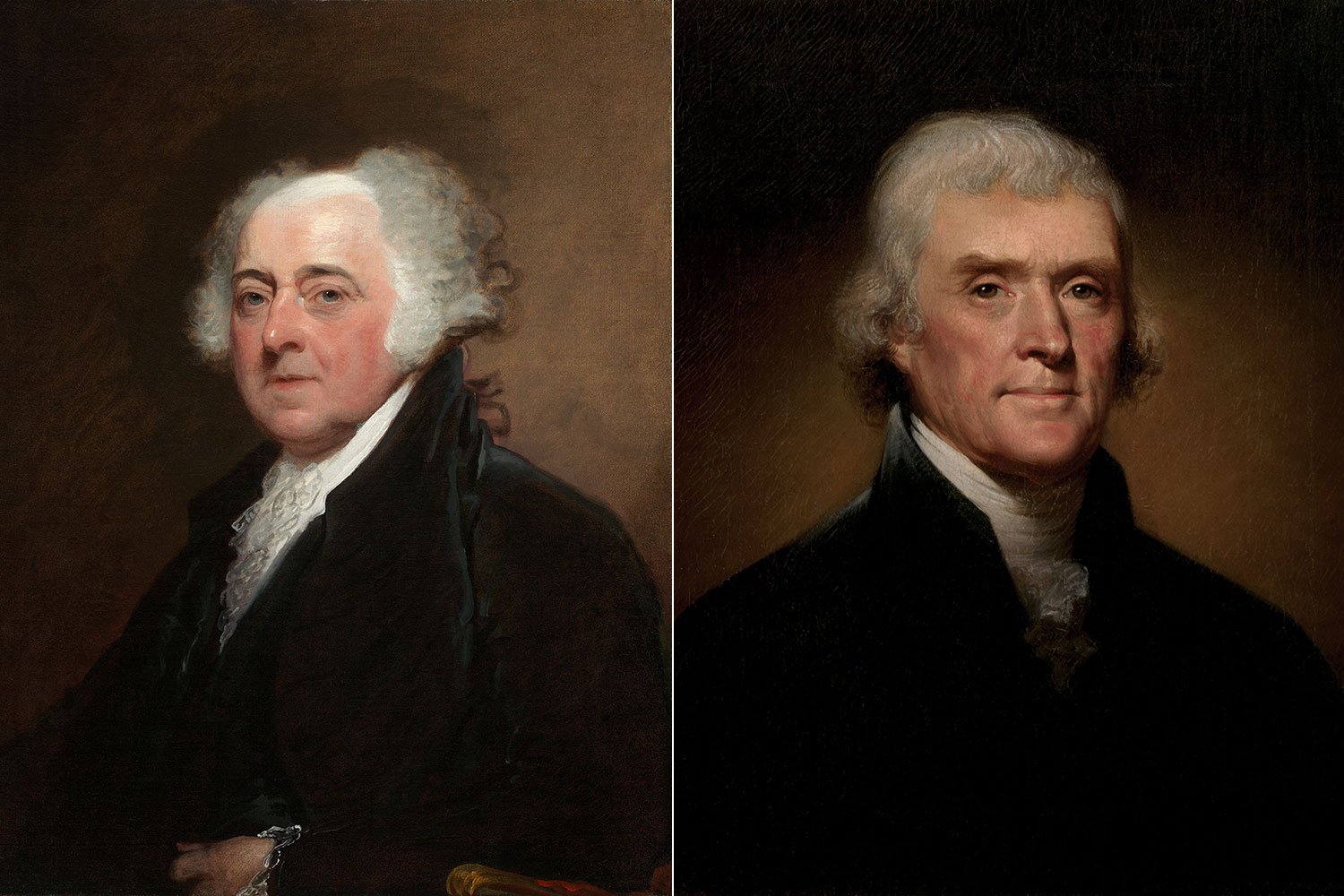

John Adams retired from the Second Continental Congress in early November 1777 and returned home to Braintree. He hoped to revive his law practice and enjoy some quiet time with Abigail and the rest of the family. However, his stay was short-lived as America had another task in mind for this tireless patriot, this time as an ambassador in Europe.

On November 27, 1777, Congress appointed Adams a commissioner to France to develop a commercial and military alliance with that nation. Adams quickly accepted the position, despite Abigail’s protests. Not one to tarry, Adams left for Europe in February 1778, but he did not go alone. At Abigail’s insistence, their oldest son, John Quincy, who was ten years old, accompanied the new envoy. The parents felt it would provide the boy with a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Following a harrowing voyage that included storms and encounters with British ships, the Adams party arrived in France on April 1, 1778. However, the treaty Adams was sent to negotiate had already been concluded in February by Benjamin Franklin, his fellow diplomat.

This Treaty of Amity and Commerce established formal relations between France and the American colonies, a first for our new nation. The terms recognized the independence of the United States, established a mutual defense pact, and ensured greater navigational rights for the Americans. It is generally considered our most important colonial era agreement.

Adams was disappointed at having taken this dangerous trip for nothing and was increasingly frustrated with Franklin for being soft on the French. To add insult to injury, in September 1778, Congress named Franklin as the Minister Plenipotentiary to France, while not providing any assignment to Adams.

This designation meant Franklin had all diplomatic power within our delegation and Adams had none. Finally, after more than a year of being underutilized, John Adams, and his son John Quincy, headed home and arrived in Massachusetts in August 1779.

Just three months later, Adams was on the road and seas again. He headed back to Paris, with both John Quincy and nine-year-old son Charles in tow, to open discussions with the French and British about ending the war. After another arduous journey that included a landing in Spain due to a leaky ship and a six-week hike over the Pyrenees, John and his sons finally arrived in the French capital on February 9, 1780.

As usual, Adams pushed for stronger French intervention in our still ongoing war and as usual it annoyed the French, especially Comte de Vergennes, the Foreign Minister. In July 1780, Vergennes informed Adams that he would only deal with Franklin.

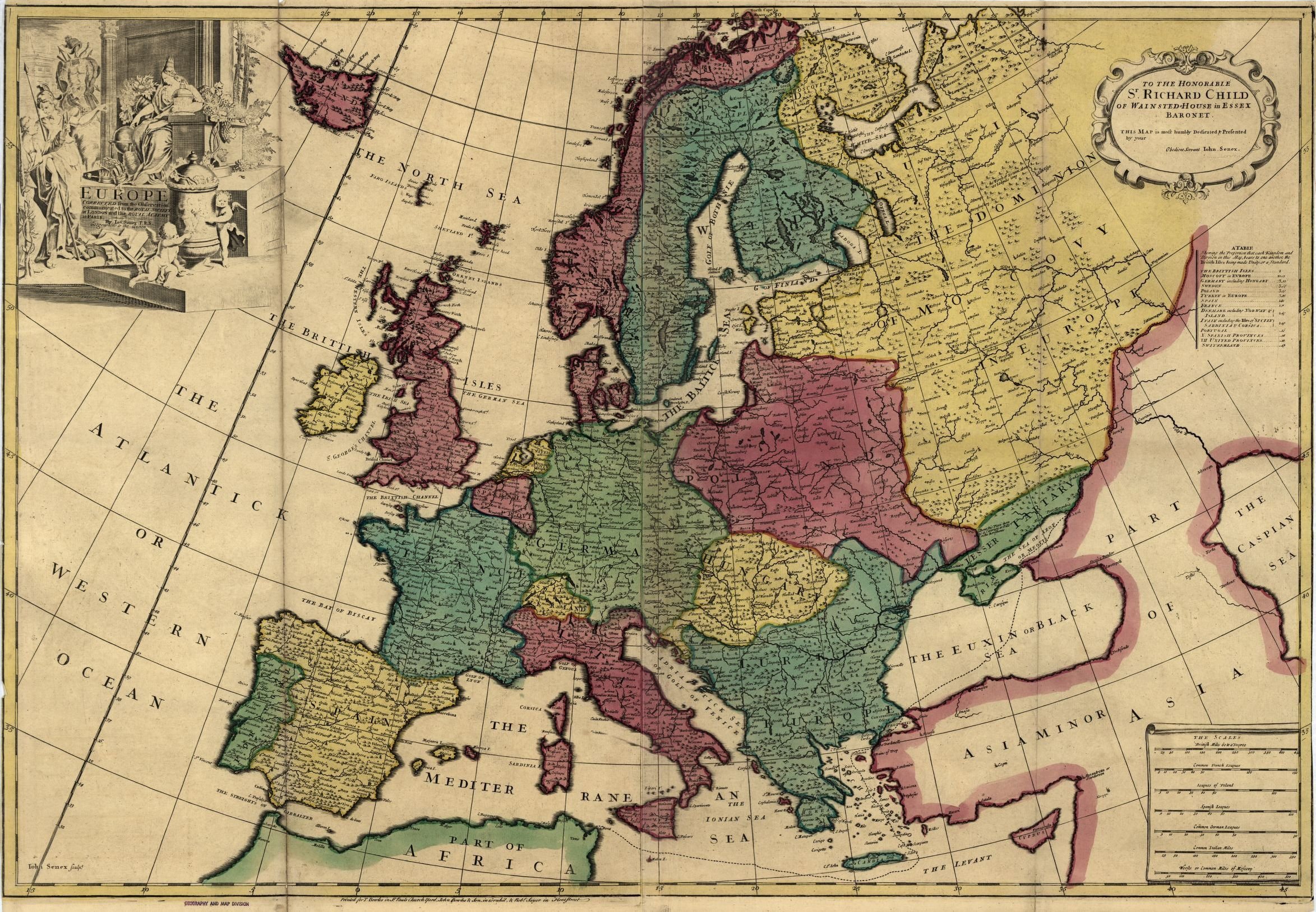

Map of Europe

Never one to rest, Adams immediately set off for Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands, to secure recognition of America as an independent state and to obtain a loan for our fledgling nation.

However, the States-General (their version of Congress) was unreceptive to the advances of Adams. They were a nation who lived and died on commerce and the seas were controlled by the English. The Dutch could not afford to have the British navy shut down their maritime trade. Until the American cause showed some signs of succeeding, they would not move.

Finally, when news of Lord Charles Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown arrived in November 1781, attitudes began to change in the Dutch Republic, and Adams immediately took his case to the people.

Going outside normal diplomatic channels, Adams published several articles in Dutch newspapers, explaining the American cause. He also called on representatives of eighteen Dutch cities asking them for their support.

On April 19, 1782, Adams’ efforts paid off when the States General in The Hague formally recognized the United States of America as a sovereign nation.

Two months later, in June, Adams secured a loan of 5 million guilders (about $2 million) from a syndicate of three Amsterdam banking houses. This money not only provided much needed assistance to the financially strapped colonies, but it also helped establish credit for the young nation.

Finally, on October 8, 1782, Adams and Dutch representatives concluded the Dutch-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce, primarily dealing with trade, shipping, and other commercial ventures.

Thus, John Adams, through his unilateral efforts in the Netherlands, gained not only credit but credibility for the country to which he was so devoted.

Next week, we will talk about John Adams securing the peace with England and his time as ambassador to King George. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.