The Newburgh Conspiracy: Washington Ends a Crisis

By early 1783, America was close to finalizing its peace agreement with England. However, the Confederation Congress had some issues to resolve with its own discontented Continental Army, as the internal threat of mutiny appeared worse than the external one posed by British forces.

The Newburgh Conspiracy: Dissension in the Ranks

We take civilian control of the military for granted today in America. However, were it not for General George Washington’s actions and words in the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy, things might be quite a bit different.

American Revolution Ends with the Treaty of Paris

After Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington in Yorktown on October 19, 1781, English officials reached the painful conclusion that the war was simply too costly to continue. Not only was the war in North America expensive to prosecute, but it was also a distraction from England’s defense of their more lucrative possessions elsewhere in the world, such as the sugar islands in the Caribbean and trading posts in India.

British Surrender at Yorktown

General George Washington led his Continental Army and the French Army under General Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau into Virginia in mid-September 1781. The combined force was on its way to Yorktown and its appointment with destiny with the entrapped British command of General Lord Charles Cornwallis.

The Yorktown Campaign

After the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse in June of 1778, the British retreated into the friendly confines of New York City. Following two lengthy campaigns (New York in 1776 and Philadelphia in 1777), England had neither crushed the Continental Army nor roused the local populace to join the British effort.

Closing Scenes of the Penobscot Expedition

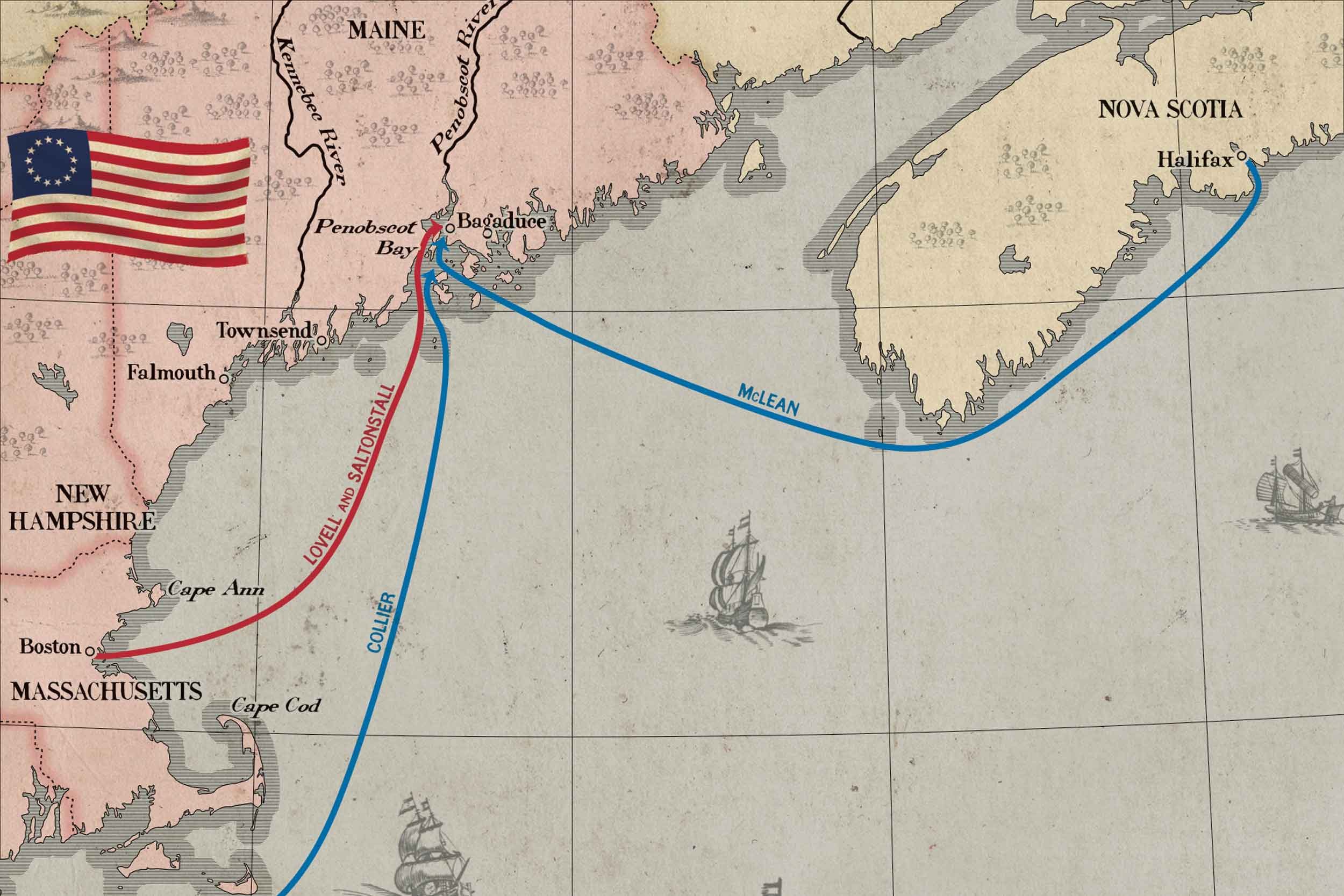

As morning broke on August 17, 1779, Vice-Admiral Sir George Collier, the commander of the small British flotilla inside Penobscot Bay, could hardly believe what had transpired over the past three days. Arriving with the expectation of a stiff fight from an American fleet much larger than his own, no battle ever materialized as the American commanders chose self-destruction to facing British guns.

Disaster for Americans at Penobscot Bay

As darkness fell in Penobscot Bay on August 13, 1779, the American soldiers and sailors in Penobscot Bay realized they were trapped by the newly arrived British fleet under Admiral Sir George Collier. With disaster staring them in the face, General Solomon Lovell, commander of the militia, and Commodore Dudley Saltonstall, the navy commander, displayed an energy that had been absent for much of the past three weeks.

Time Runs Out for Americans at Penobscot Bay

The Penobscot Expedition which started so well with the successful assault up the cliffs at Dyce’s Head to the plateau at the top of the Bagaduce Peninsula on July 28, quickly ran out of steam. Three main impediment was an inter-service squabble between the army commander, General Solomon Lovell, and his naval counterpart, Commodore Dudley Saltonstall. Showing a reluctance to engage the enemy that seemed to border on cowardice, Saltonstall would be an obstacle that Lovell could not overcome.

The Penobscot Expedition

In June 1779, with the British establishing a foothold in Penobscot Bay 240 miles northeast of Boston, the Massachusetts General Assembly sprang into action. The men chosen by the Assembly to lead the expedition to oust the Brits was an interesting group, all New Englanders and not a professional soldier among them.

British Forces Establish Foothold in Penobscot Bay

The greatest naval disaster in our nation’s history until Pearl Harbor was a largely forgotten episode that took place on the remote coast of Maine in the summer of 1779. The location was Penobscot Bay and the event proved to be an embarrassment caused by ineptitude, cowardice, and lost opportunities.

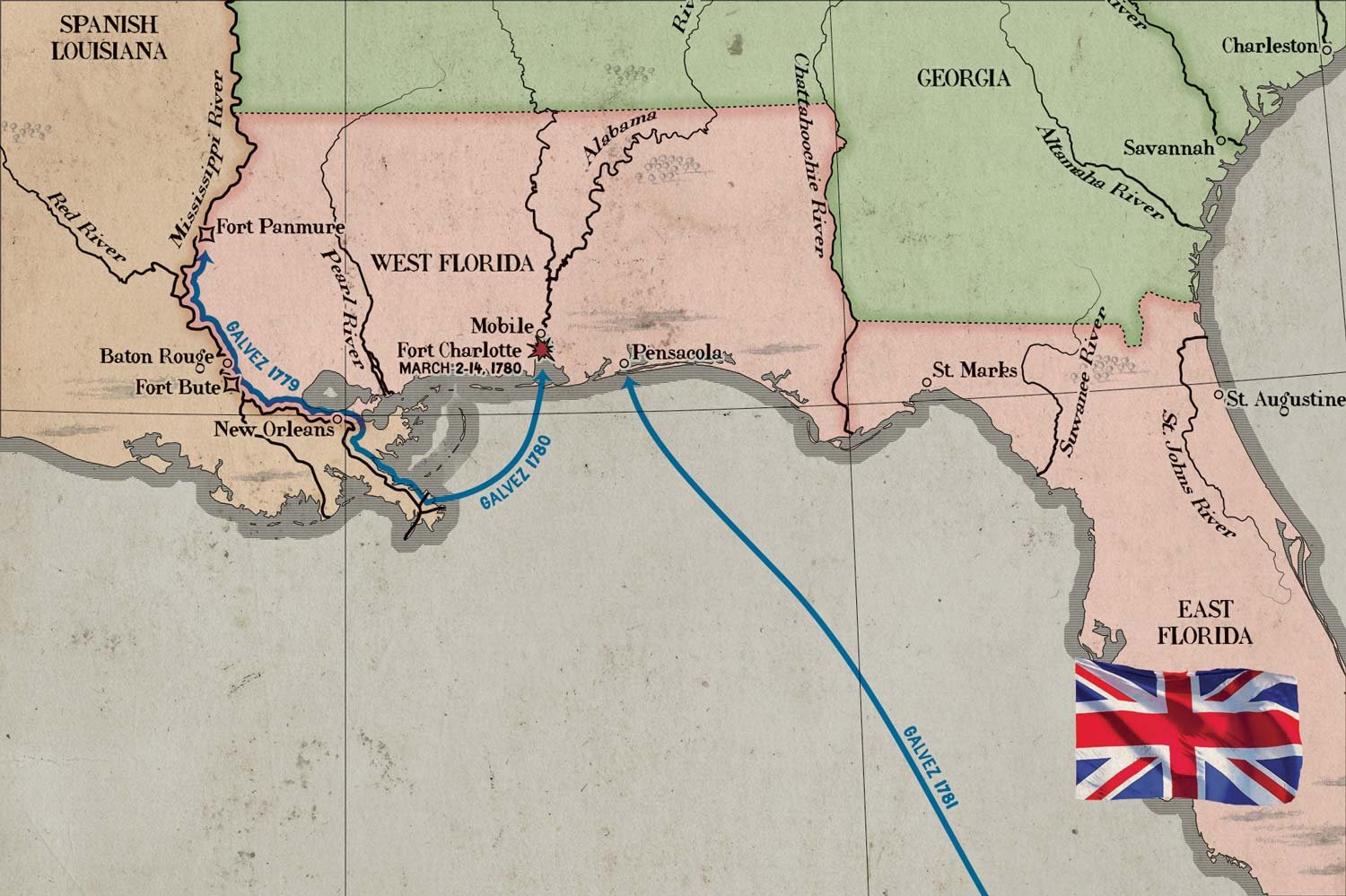

Spain Recaptures Florida

Because of Spain’s numerous possessions along the Gulf Coast and in Central America, France and Spain jointly decided to have Spain fight the British throughout the southern theater and in the Mediterranean, while France would send their soldiers and navy to help the thirteen American colonies. It is the reason why the French were at Newport, Savannah, and Yorktown while Spanish soldiers were not, leaving the mistaken impression in most American’s minds that France was our only ally in the American Revolution.

Kentuckians Find an Ally in Spain

With British fortune in the American Revolution at low tide in 1779, King Carlos III of Spain and his chief minister Jose Monino, Count of Floridablanca, decided the time was right for Spain to enter the war. But, for strategic reasons, they did not do so as a formal ally of the United States, but rather as one of France, their neighbor and cousin. As time would tell, Spain’s decision was instrumental in securing American independence.