The Constitution of the United States

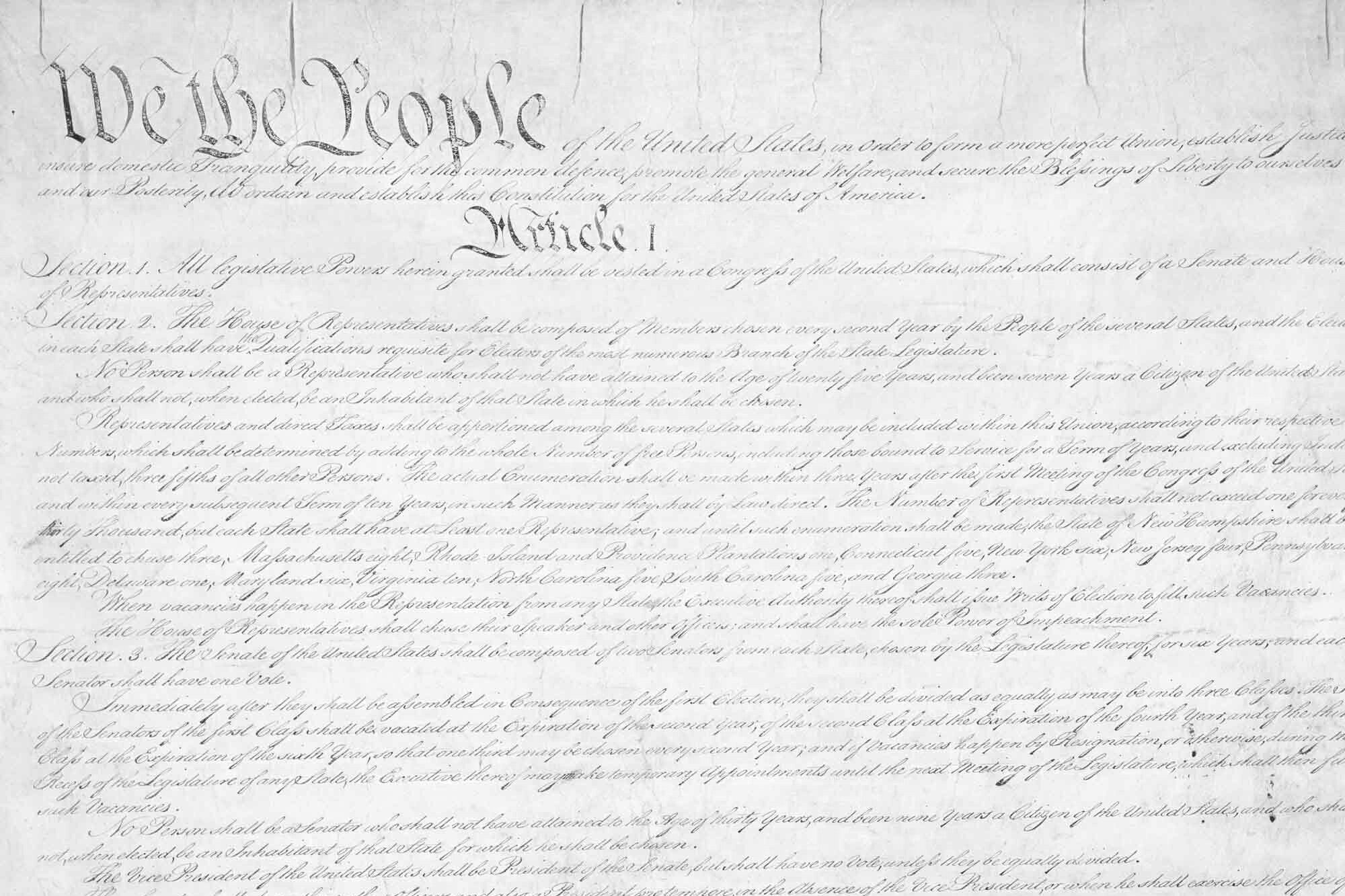

Preamble. The opening phrase of the preamble, “We the People,” spoke volumes regarding upon whose authority the Constitution rested and suggested the unanimity of country and purpose that this new Constitution would create. It was written by Gouverneur Morris, a delegate from New York, and his eloquent words speak for themselves.

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, ensure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution of the United States of America.”

Article 1. LEGISLATURE. Article 1 lays out how Congress will be structured and what powers it will be granted. In a clear indication of where the delegates felt the bulk of the new powers created by the Constitution should reside, roughly half of all the words in the Constitution are found in Article 1.

This section explains that Congress will be comprised of two houses, one based on state population (House of Representatives) and one with equal representation to all states regardless of their size (Senate). It further details the terms of office and the manner in which they will be selected to serve.

Article 1 gives Congress the “Power To Lay and collect Taxes,” “borrow Money,” and “regulate Commerce.” It authorizes Congress to “coin Money,” “establish Post Offices,” and “raise and support Armies” and “provide and maintain a Navy.” The list goes on and it is extensive.

Interestingly, Article 1 is the only place in the Constitution where the Vice President is mentioned. He shall be “President of the Senate,” and his only task is to break tie votes in the Senate. John Adams, our first Vice President, called the position “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man has contrived.” However, it should be remembered that nine of these insignificant Vice Presidents became President not through election but through the death or resignation of a President.

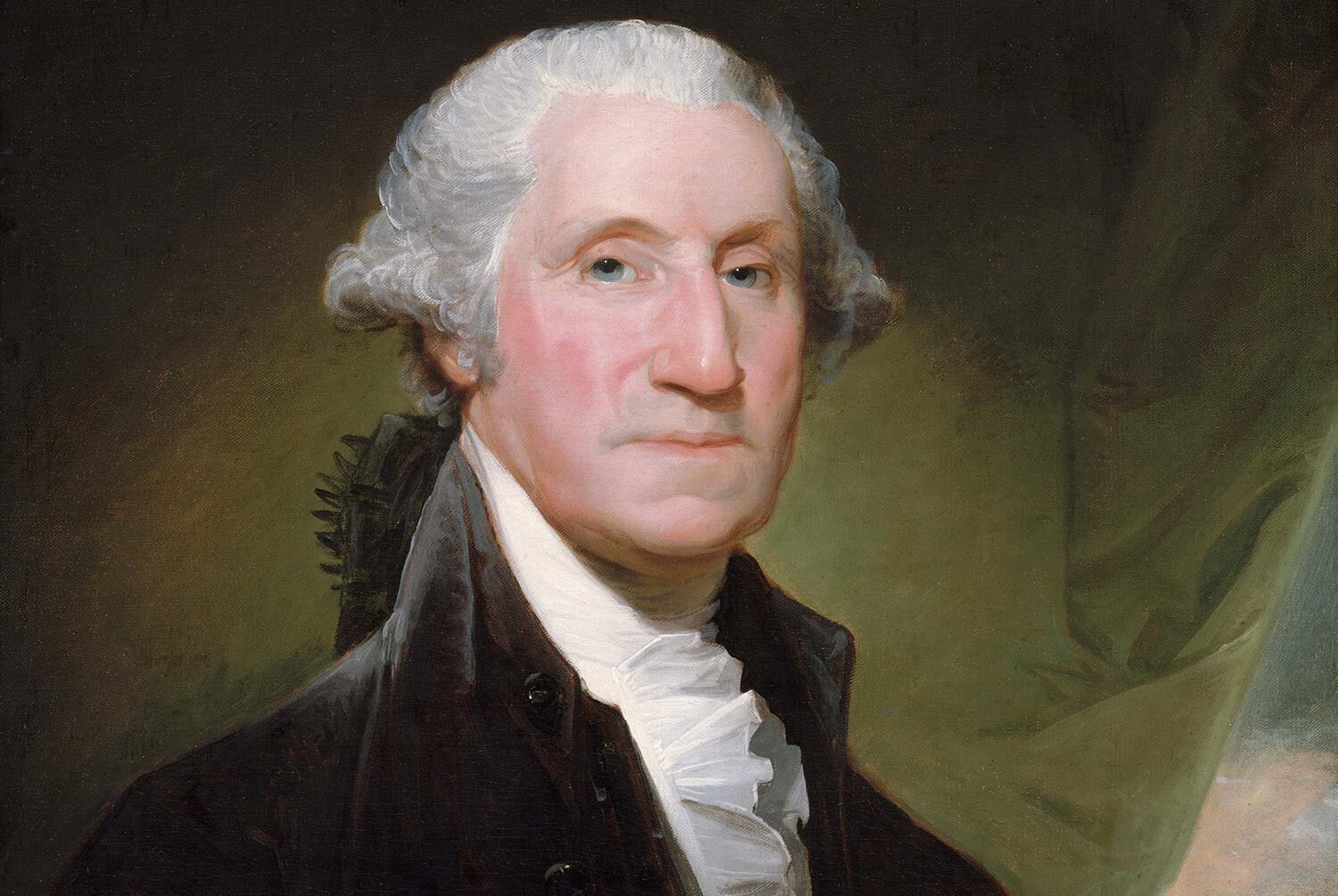

Article 2. EXECUTIVE. Article 2 creates an executive branch strong enough to compete with the legislature. The amount of power vested in the executive branch was a point of great contention and was influenced in no small measure by the comforting knowledge that George Washington would be the first man to fill this role.

Article 2 declares the President to be the “Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy” thereby imposing civilian control over the military. It gives the President the power to veto legislation, thus providing a check on Congress. It also grants the President the authority to enter into treaties and “to appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States” but only with the “Advice and Consent of the Senate”; thereby allowing Congress to place a check on the Executive.

It declares the term of office shall be four years, but it does not declare how many terms a President could serve. That would change with the 22nd Amendment in 1951. It further stipulates that the President must be at least thirty-five years of age. Teddy Roosevelt was the youngest to ever serve as President at 42 years and 10 months following the assassination of President William McKinley, while John Kennedy was the youngest ever elected at 43 years and 7 months.

Article 3. JUDICIARY. Article 3 creates our court system and vests power in “one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” Thus, Congress has a check on the size and extent of the judicial branch.

However, in the very next paragraph, the Court is given the power to judge “all cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution.” In other words, it can judge all laws passed by the legislature and signed by the executive, thus creating a check on both the legislative and executive branches.

Importantly, once appointed, the judges “shall hold their Offices during good Behavior” which basically means for life. Thus, federal judges are not beholden to either Congress or the President for remaining in office, thus creating an independent judiciary, one of the pillars of a democracy.

Article 4. STATES. Article 4 explains how the various states will interact and cooperate with one another and how “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.”

With an eye towards our nation’s expansion, Article 4 also provides for the addition of new states and declares that they will be accorded privileges equal to the existing states.

Article 5. AMENDMENTS. Article 5 allows for amendments to the Constitution thus providing flexibility for future generations to amend the Constitution as the need arises. Because changing a foundational document is no small matter, Article 5 requires any changes pass over a relatively high bar. Specifically, “two thirds of both Houses…shall propose Amendments to this Constitution” and they must be “ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States.”

Since the implementation of the Constitution, we have added 27 amendments to the Constitution. The first ten are known as the Bill of Rights, ratified on December 15, 1791. The most recent amendment dealing with Congressional salaries was ratified in 1992 but first proposed in 1789.

Article 6. SUPREMACY. Article 6 declares that the “Constitution…shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” Importantly, it further requires that all “Senators and Representatives…and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States…shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution.”

Article 7. RATIFICATION. Article 7 explains that “the Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution.” Delaware was the first to ratify the Constitution, doing so on December 7, 1787, and New Hampshire has the honor of being the ninth state to ratify when it did so on June 21, 1788, thus officially making the Constitution the “Law of the Land.”

After four months of debate, the Constitution of the United States was approved on September 17, 1787, and, after ratification by the states, went into effect on March 4, 1789. What the delegates ultimately agreed to and sent to the states was a 4,543-word masterpiece of political thought. It is a document that has stood the test of time and is the longest standing written constitution in the world.

Next week, we will discuss George Washington’s first term as President of the United States. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The opening phrase of the preamble, “We the People,” spoke volumes regarding upon whose authority the Constitution rested and suggested the unanimity of country and purpose that this new Constitution would create. It was written by Gouverneur Morris, a delegate from New York, and his eloquent words speak for themselves.