The Slavery Question at the Constitutional Convention

When delegates met at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, one of the most troublesome questions was what to do about slavery. Not whether it should be abolished, because even the most vehement abolitionist recognized this was neither the time nor the place for that fight. The issues to be decided were how would slaves be counted in the census and whether the states or the central government would control the institution, and what that control would look like.

All delegates recognized the terrible inconsistency between slavery and the words expressed in the Declaration of Independence. But they understood the task at hand was to create a new form of national government that could prosper under the conditions that then existed in the country, and slavery was a reality, not just in North America but throughout the world. The Convention would not and could not change that.

In 1787, slavery was widespread, existing in Islamic nations in Africa and on European sugar plantations in the Caribbean and South America under terribly harsh conditions and would remain so for decades to come. In comparison, North American slavery was somewhat isolated and the first ever movement to abolish slavery had already taken root within the United States.

By the time of the Constitutional Convention, five states (Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island) had passed legislation to end slavery, either immediately or over time. Pennsylvania’s Act of the Gradual Emancipation of Slavery, passed on March 1, 1780, was the first slave abolition law passed in human history by an elected body.

But where it did exist in the Deep South, slavery was critical to the economy as slaves represented 25% to 43% of the total population in the five largest slave holding states (South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina). In absolute numbers, Virginia had almost 300,000 slaves, more than the entire population of seven of her sister states. Consequently, slave states had a lot to lose if slaves were not counted in the census when determining representation in Congress.

In 1787, there was no King Cotton as Eli Whitney’s cotton gin was six years in the future and slavery seemed to be dying a natural death as more slave owners questioned the institution’s economic viability. Men like Roger Sherman from Connecticut advised letting it die on its own rather than adding abolition to the Constitution and thereby creating an insurmountable obstacle to the new government.

Other northern delegates who did not approve of slavery felt the same way. Gouverneur Morris of New York called it a “nefarious institution, the curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed” but even Morris was not prepared to call for its abolition. Even many of the 25 delegates who owned slaves spoke against the institution and wished a solution could be found to end it.

In one of the Convention’s more heated moments, George Mason, owner of over 200 slaves, made an impassioned speech on the evils of the institution, saying it made “petty tyrants” of all masters. Mason placed much of the blame on England for starting the slave trade during our colonial era but then went further and criticized New England ship owners for their greed in carrying slaves to North America on their ships. This was too much for Oliver Ellsworth from Connecticut, where slavery had been abolished in 1784. He rose and asked Mason why he did not simply free his slaves if he found slavery so offensive. Mason’s response was not recorded.

“George Mason.” Wikimedia.

The central issue was that the southern states would not agree to the proposed Constitution if the abolition of slavery was included in it. General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney from South Carolina made the case quite simple, “South Carolina and Georgia cannot do without slaves.” John Rutledge, also from South Carolina, said the true question was “whether the Southern states shall or shall not be part of the Union.” Clearly, had the abolition of slavery been a requirement of the new Constitution, the Convention would have ended and with it any attempt to create the stronger federal government required to maintain the fledgling republic.

The main points of contention were how would slaves be counted when considering representation in Congress and would the institution itself be controlled by the states or the national government. The issue came to a head in August after the Committee of Detail presented a draft Constitution for the delegates to consider. In the document, there was a clause that allowed the federal Congress to pass navigation acts and “regulate commerce among the several states.” Since the slave trade was considered commerce, the control of slavery would thus pass from the states to the central government under the new Constitution.

Delegates from slave states said this provision was a non-starter and a compromise must be found. The deal finally reached was that navigation acts could only pass with a two-thirds majority of Congress, the importation tax on slaves could not exceed $10 per head, and the Southern states agreed that the importation of slaves would be forbidden after 1808. A clause, known as the Fugitive Slave Clause, was also added that required slaves to be returned to their owners even if the slave made it to a state that did not permit slavery.

Perhaps most importantly, it was agreed that slaves would be counted as three-fifths of a person for census purposes, greatly increasing representation and political power for southern states in Congress. This was known as the “federal ratio” and, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, “no union could possibly have been formed without it.” So sensitive was this matter that those drafting the final version of the Constitution avoided the use of the word “slave,” referring to this agreement as “three-fifths of all other persons.”

Next week, we will discuss the Constitution of the United States. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

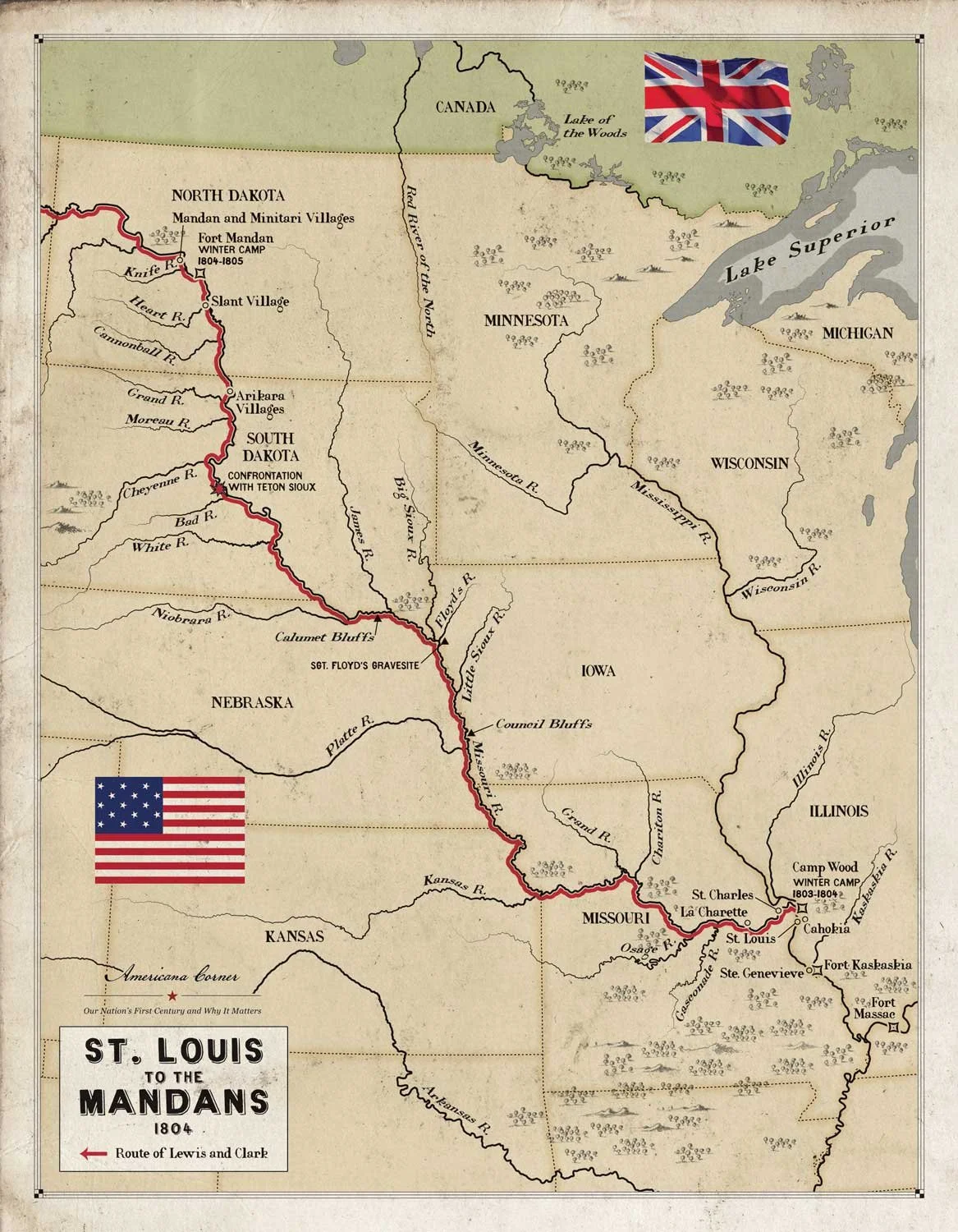

The Corps of Discovery arrived at the Mandan villages near present day Bismarck, North Dakota, in late October 1804 and prepared to settle in for the long winter. For the past five months, the Lewis and Clark expedition had spent most days rowing or pushing their keelboat against the Missouri River’s powerful current, and the men were ready for a break. They were now 1,300 river miles upstream from the nearest civilized settlement and, although they did not know it, they had over 2,000 miles to go to reach the Pacific Ocean.