The Federal Convention Opens

In the years immediately following the successful conclusion of its war for independence, the United States struggled to survive under the Articles of Confederation. The nation’s leaders knew something had to be done to fix its many issues for this great experiment in democracy to continue.

In September 1786, delegates from five states met in Annapolis, Maryland, to discuss trade matters, but the dialogue quickly expanded into other areas. The outcome of this meeting was to recommend to Congress that a convention of all states be held in Philadelphia in May of the following year to review how to fix broader issues within the existing system of government.

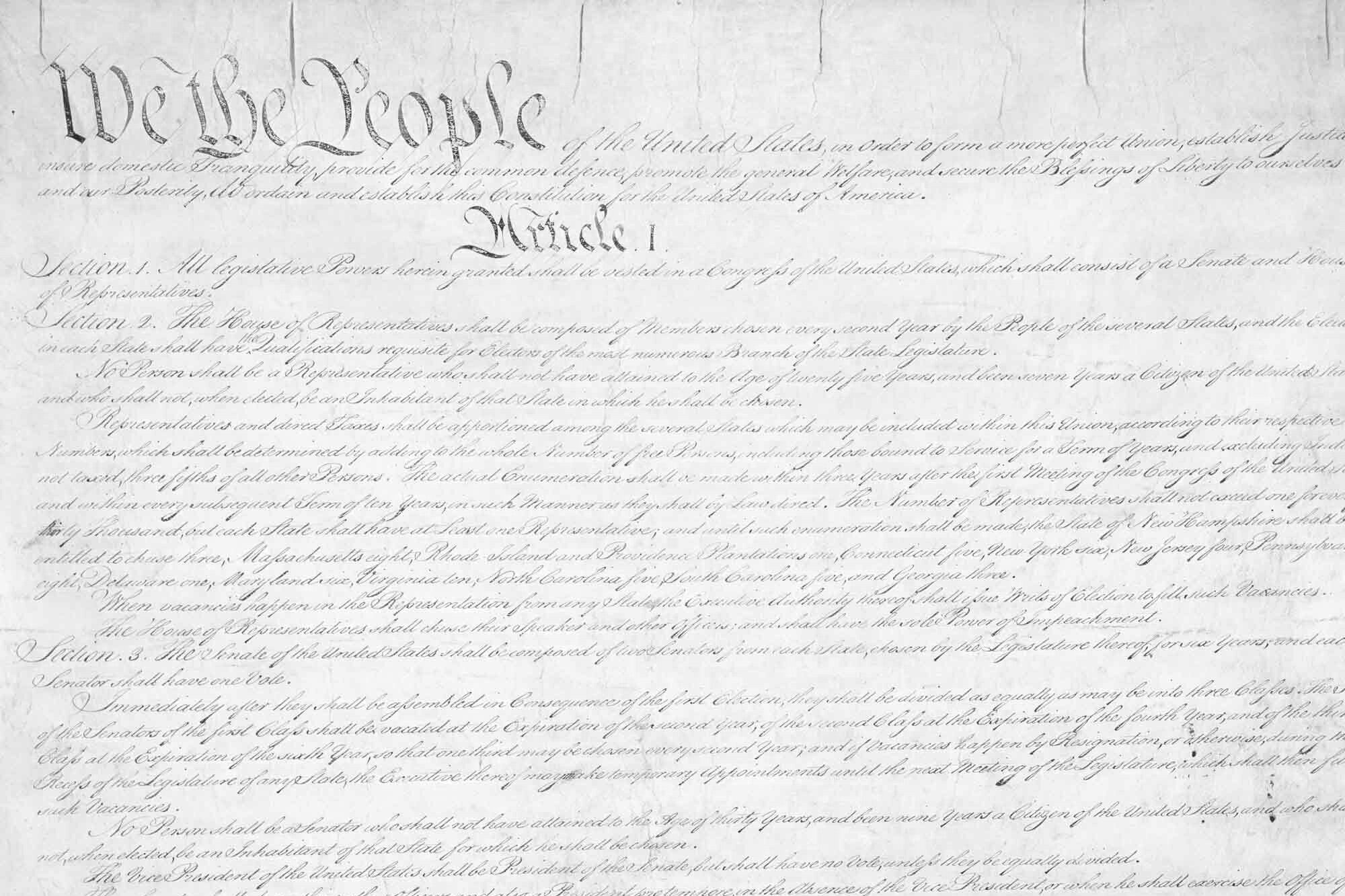

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, essentially our first constitution, had been in force since February 1, 1781, but it had proven to be deeply flawed. Its provisions simply did not provide enough authority for the federal government to effectively govern the country.

The Confederation Congress lacked the authority to raise an army without the approval of the states, and the Articles made foreign policy matters challenging as all treaties had to be unanimously approved. Most importantly, they did not empower the federal government to levy taxes. Instead, the Confederation Congress was forced to rely on the states to agree to their many requests for funding.

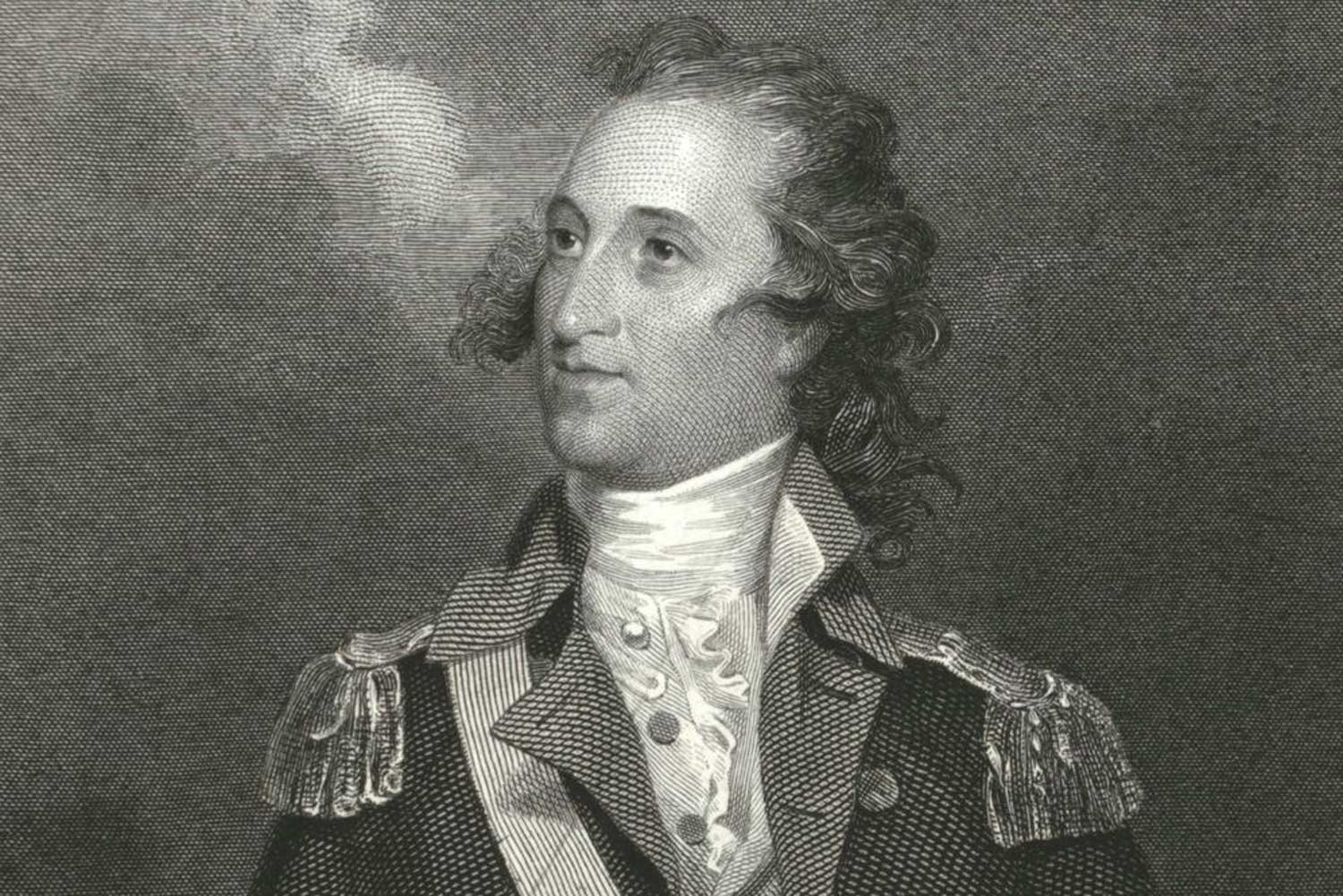

To add credibility to the proposed convention, at the time called the Federal or Philadelphia Convention, the primary organizers, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, felt it was critical for George Washington to attend. Without his presence and implied approval, it would be difficult to get the American people to accept any changes to the existing government.

John Vanderlyn. “James Madison.” White House Historical Association.

Washington hoped for revisions to the federal government, stating earlier he did not think the United States could “exist long without…a power which will pervade the whole Union in as energetic a manner as the authority of the state governments.” However, he was not anxious to personally participate, recognizing statecraft and political wrangling was not his strong suit, and he worried about the success of the undertaking. But never one to refuse a duty when called to serve, Washington reluctantly agreed to represent Virginia at the gathering.

When the delegates convened in Philadelphia on May 25, 1787, twelve states were represented, only Rhode Island refused to send a delegation. Eventually, a total of seventy-four delegates were appointed by the various states but only fifty-five delegates ever attended the Convention, and there were rarely more than forty delegates present.

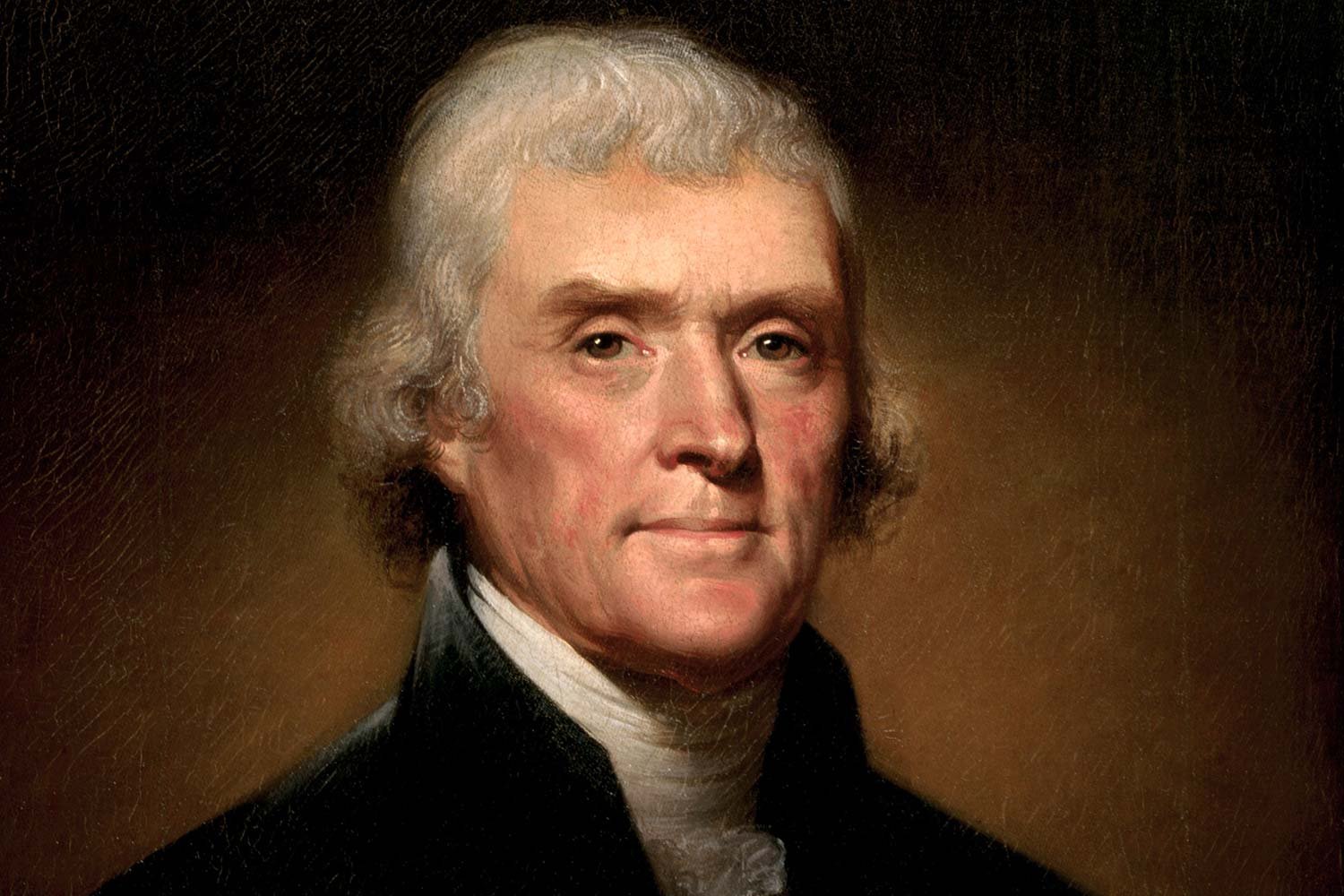

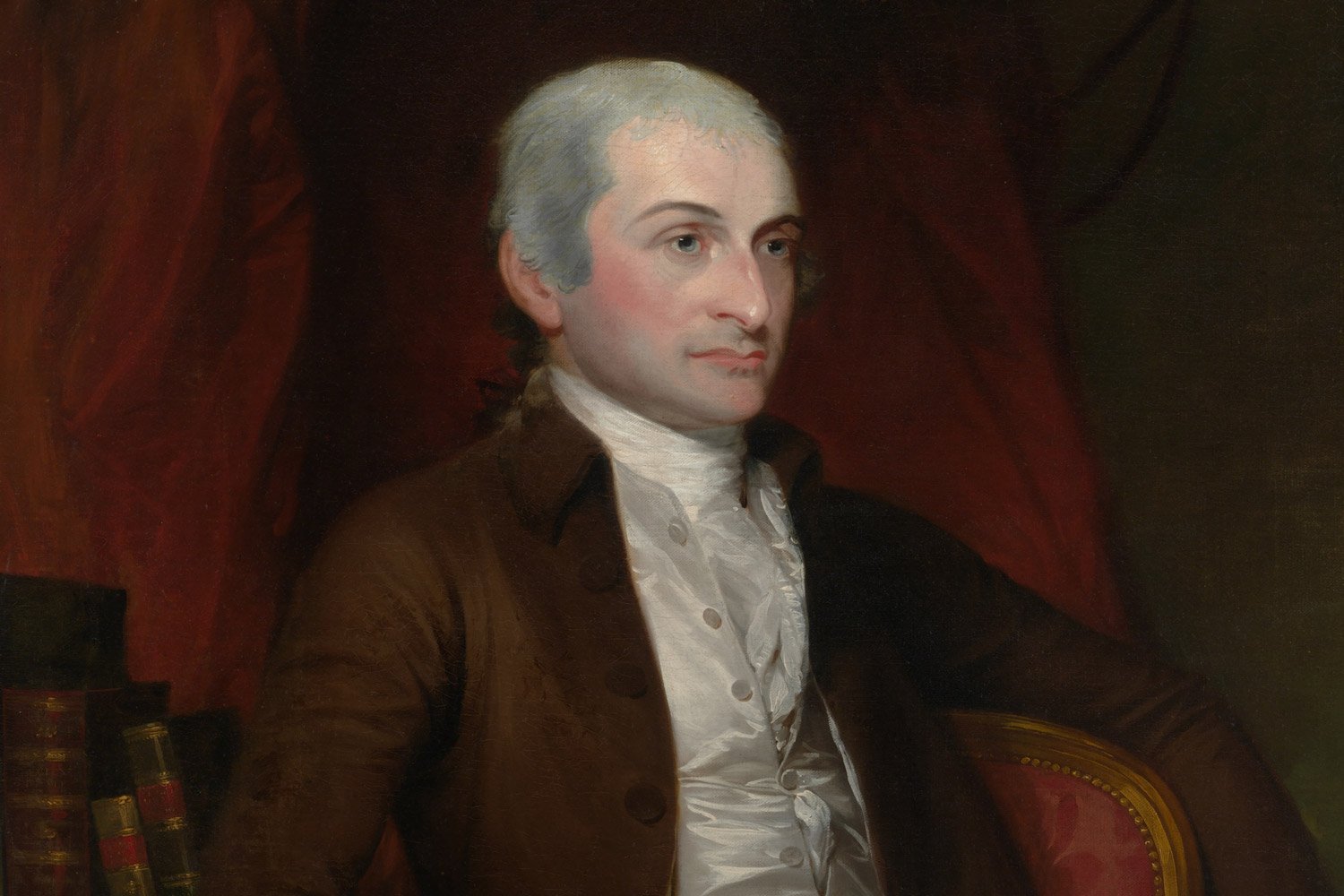

There were three men who were conspicuous by their absence; John Adams was in London as ambassador to Great Britain, Thomas Jefferson was in Paris at the Court of King Louis XVI who was only two years away from losing his crown and his head in French Revolution, and Patrick Henry who was asked but refused to attend. Henry, arguably as revered by Virginians as George Washington, was a strong states rights man and declared he “smelt a rat” with this Federal convention and chose to stay away.

The first order of business was to unanimously appoint Washington to preside over the convention. Over the course of the next four months, Washington did not participate much in the day-to-day discussions, preferring to let those better versed in political philosophy have the floor. He was also concerned that his opinions might sway the delegates and he wanted to create an atmosphere of compromise among the various factions. However, there is little doubt that his steady leadership was critical to the success of the Convention.

As the credentials of the various states were read aloud and the delegates formally introduced, it was clear that the state legislatures did not desire a new Constitution. The instructions from most of the states declared the goal of the convention was “for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation” and many of the delegates intended to jealously guard the interests of the states.

Despite these instructions, Madison and Hamilton soon moved to create an entirely new constitution, based on a stronger federal government. Men who would later become known as “Federalists”, felt the existing Articles did not accomplish the twin goals of creating a vigorous central authority but with enough constraints on it to protect the rights of its citizens.

As James Madison later eloquently explained in Federalist No. 51, “if men were angels, no government would be necessary” and if the government were run by angels “neither external nor internal controls would be necessary. In framing a government that is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

These opposing views would generate intense debates over the course of four months in the summer of 1787. Next week, we will discuss key debates at the Constitutional Convention. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

As a boy growing up in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson listened to his father tell captivating stories of the pristine wilderness beyond the Appalachian Mountains and dreamed of what opportunities lay in the uncharted lands of North America. As Jefferson grew to manhood, he became a proponent of national expansionism, recognizing that the future greatness of the country lay outside the original thirteen colonies.