The Jay Treaty Cools Rising Tensions Between America and England

The Jay Treaty, officially known as the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, was signed on November 19, 1794. Its primary goal was to cool rising tensions between England and America over issues remaining from the American Revolution.

While the Treaty of Paris of 1783 had ended the American Revolution, several provisions laid out in the agreement had not been followed by the two countries since its signing. This failure to comply with the treaty’s requirements led to disagreements and war was becoming a real possibility.

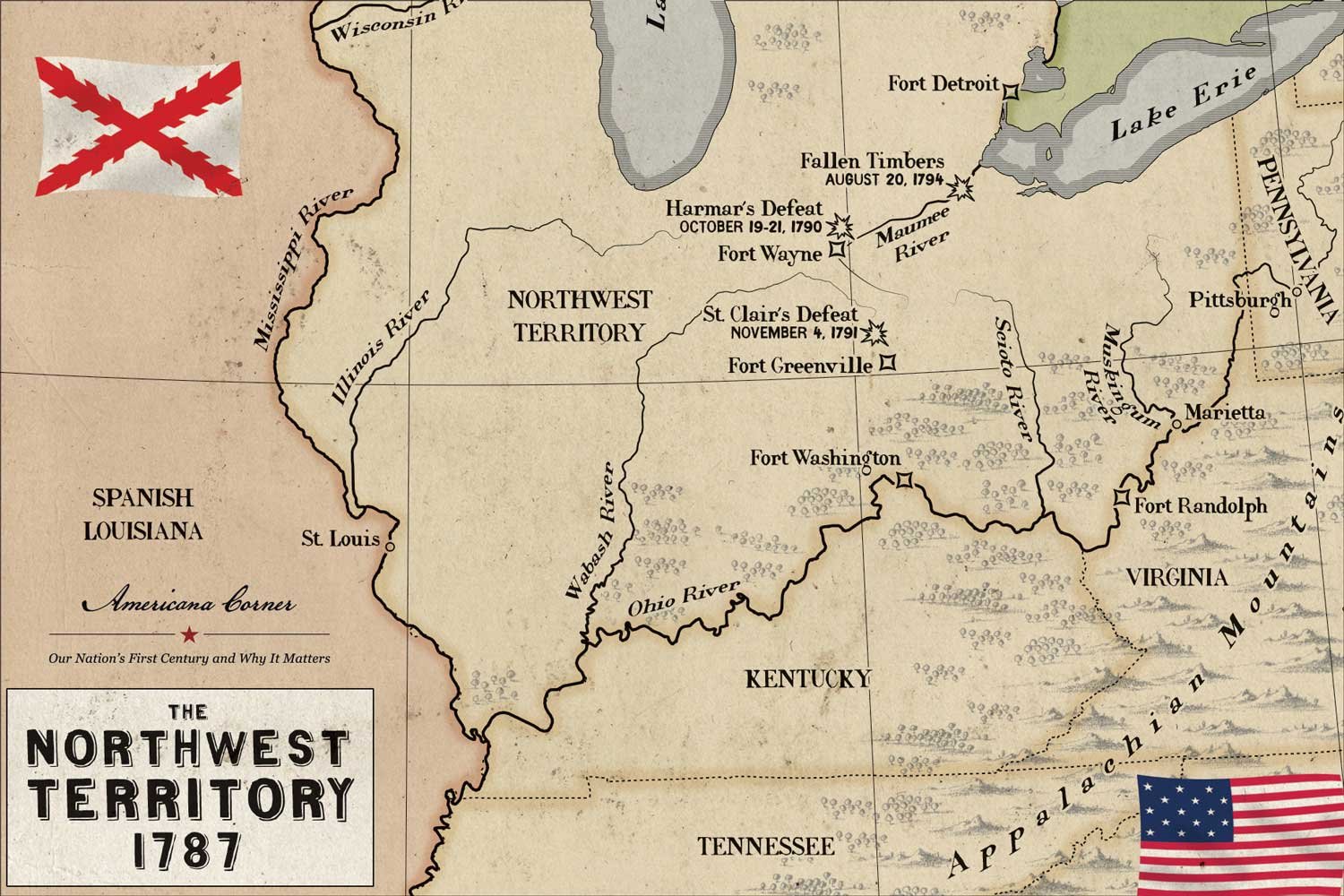

One of the main points of contention was that the British had never evacuated their forts in the Northwest Territory and, to make matters worse, they encouraged their Native American allies to terrorize any settlers in the region. The British had also continued their impressment of sailors on American vessels (taking British citizens serving on American merchant ships off them to man British warships). They also had flooded American markets with British exports, while denying American commerce entry into many foreign ports.

On the other hand, American courts continued to block attempts by British creditors to collect legitimate debts from Americans incurred during the Revolution. Additionally, despite guarantees in the 1783 treaty to return confiscated estates to Loyalists, American authorities refused to restore them.

President George Washington worried that our new nation was drifting towards a war it was ill-prepared to fight. The Treasury was not well stocked and a war with our largest trading partner would devastate the economy.

Moreover, we had only a small standing army, the recently created Legion of the United States. We also had no navy, despite the passage of the Naval Act of 1794 which called for the building of a naval force of six frigates. Due to a lack of funds and the constant fear of the Jeffersonians of a powerful central government, the first of these vessels would not sail until 1797 when French depredations forced Congress to act.

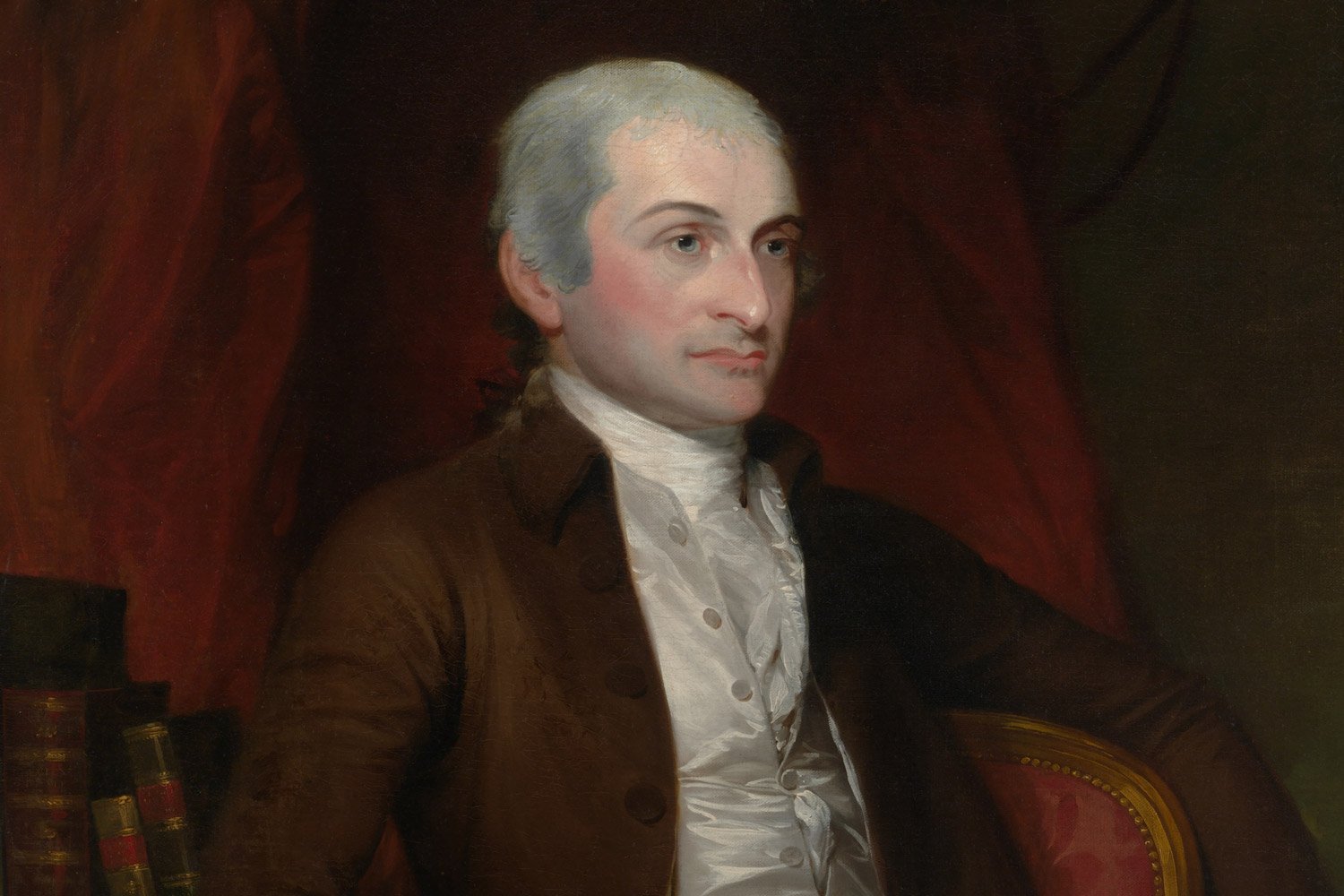

To prevent this potentially devastating conflict, President Washington sent John Jay, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, to England to negotiate a settlement with the British. The terms Jay worked out with Lord Grenville, Britain’s lead negotiator, included the evacuation of British forts in the northwest and a commercial treaty granting the United States “most favored nation” status with England.

Other key points of disagreement like wartime debts and boundary disputes, such as along the Canadian-Maine border, were submitted to arbitration. After several years, the arbitration board announced their decisions, which greatly favored the American position. While the British were awarded 600,000 pounds for unpaid pre-1775 debts, the United States received $11.6 million for damages to American shipping.

By the two most important measures, the Jay Treaty was a success. It kept us out of war with the world’s strongest nation, England, and we gained improved trading status with our largest trading partner and American goods gained access to more markets. However, when the terms were announced in America, it was initially viewed in a negative light and protests erupted across the country. At a rally in New York, protestors hurled stones at Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and treaty opponents besieged the presidential mansion in Philadelphia.

"Jay Treaty." Wikimedia.

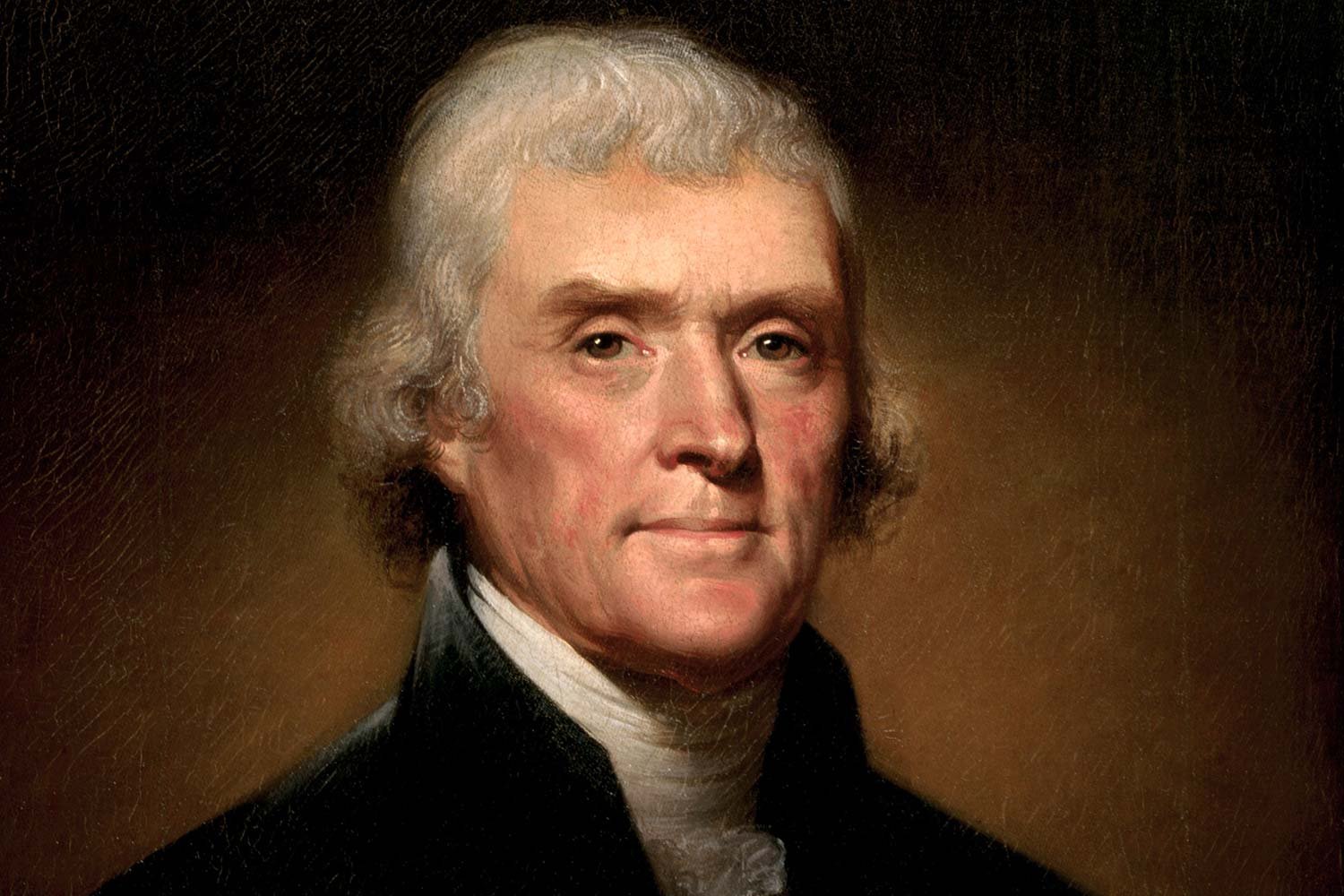

This antipathy largely stemmed from an anti-treaty propaganda campaign initiated by the French leaning Democratic-Republican party of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who saw the agreement as too pro-British. They were opposed to any legislation or acts that brought America closer to England, who the Jeffersonians considered our arch enemy. Despite the Democratic-Republican attempt to derail the treaty, it was ratified on June 24, 1795, by the Senate, where the Federalist Party held sway, and it went into effect on February 29, 1796.

Interestingly, the Jay Treaty was one of the key issues debated during the presidential election of 1796. By then, American public opinion had turned against the French and had become supportive of the Jay Treaty, which helped John Adams, the Federalist Vice President, defeat Jefferson to become our nation’s chief executive.

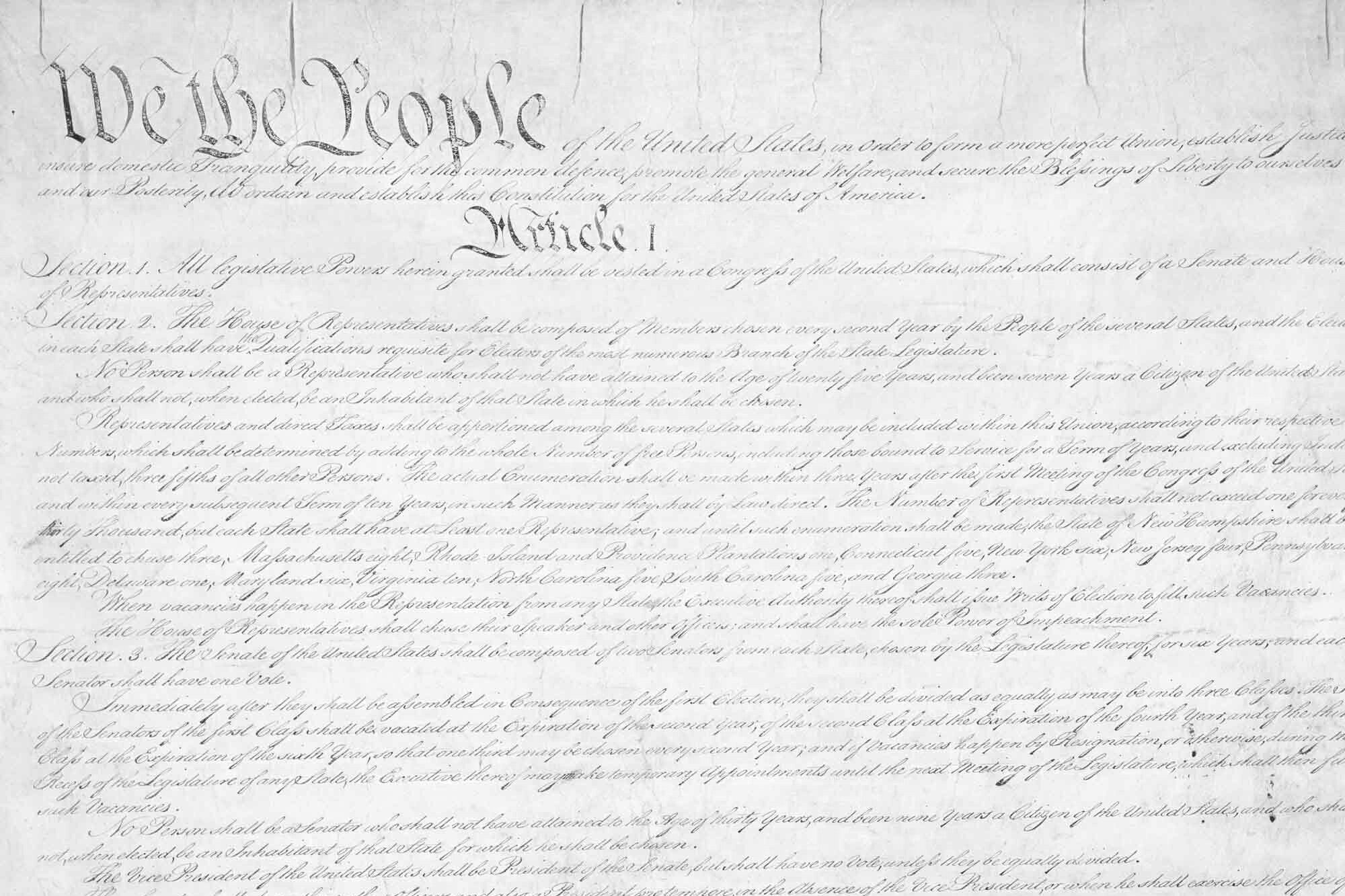

So why should the Jay Treaty matter to us today? When the Jay Treaty was ratified, our country had been operating under the new Constitution for just a few years and was still finding its way. The last thing we could afford was another costly war, especially with England, the world’s foremost power and our main trading partner. President Washington, perhaps more so than anyone else, fully recognized this fact.

The treaty struck by John Jay was instrumental in calming tensions between England and the United States. Washington’s decision to accept the terms we received from the British in the Jay Treaty, in the face of severe criticism from the Jeffersonians and against popular opinion, took tremendous courage and was the best course for the nation.

Next week, we will discuss the Treaty of San Lorenzo. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

As a boy growing up in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson listened to his father tell captivating stories of the pristine wilderness beyond the Appalachian Mountains and dreamed of what opportunities lay in the uncharted lands of North America. As Jefferson grew to manhood, he became a proponent of national expansionism, recognizing that the future greatness of the country lay outside the original thirteen colonies.