Creating the Constitution: The Executive

One of the major defects in the Articles of Confederation was the lack of an executive, that single individual who was to some degree in charge of the nation. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, this flaw was addressed and the amount of authority to be vested in the office was a major point of contention.

To appreciate why this issue was so controversial, it is critical to understand what a head of government looked like at that time. Simply put, it was a hereditary monarch such as a king, emperor, or czar. These people ascended to their position not based on merit but rather because of the good fortune of their birth.

These rulers, in most cases, had absolute authority over their subjects. They decided what religion the people could practice, where they could travel, what they could own, and in some cases who they could marry.

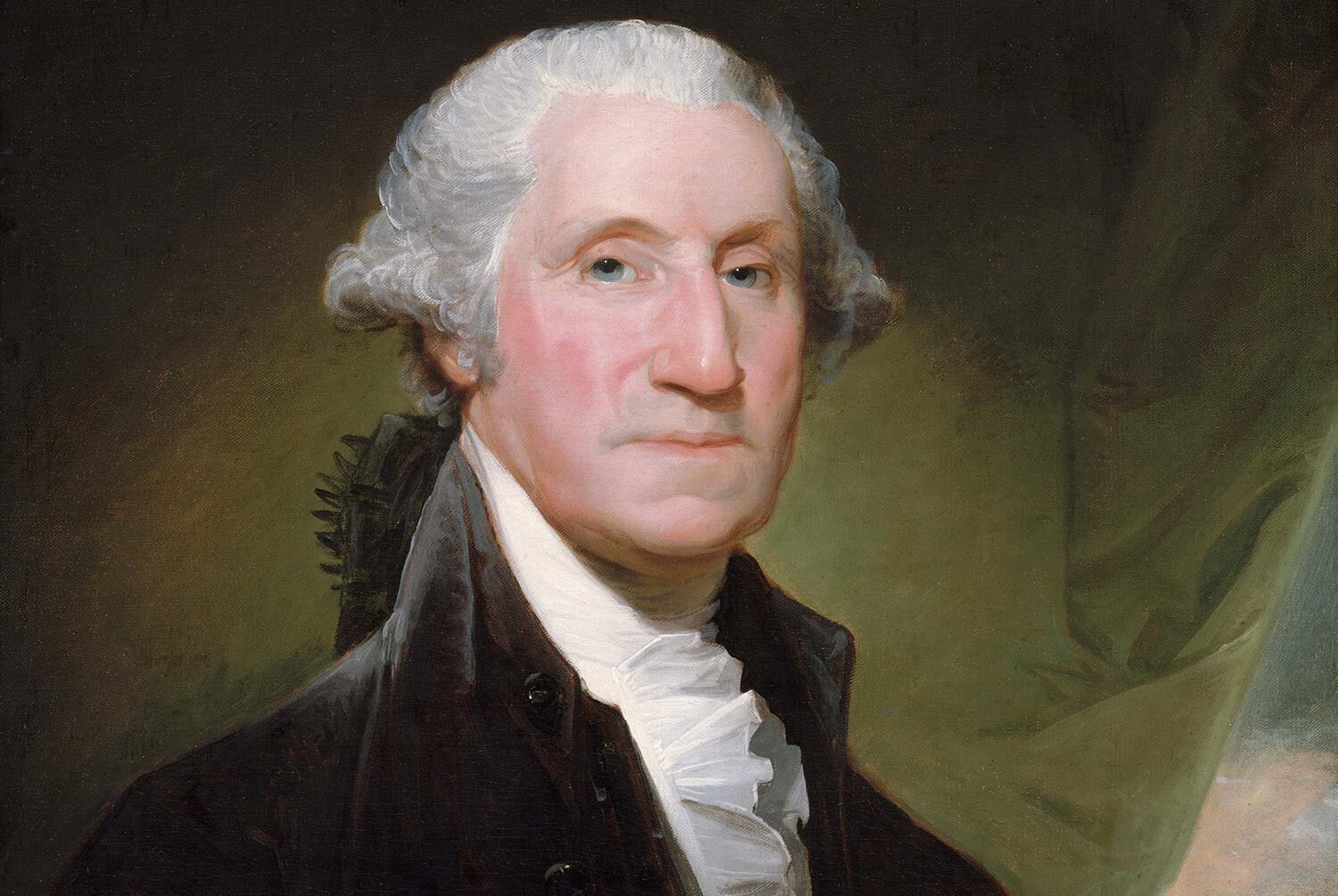

The delegates knew first-hand that many of the troubles which led to our separation from England were a direct result of decisions made by King George. He had consistently shown himself to be unsympathetic to his subject’s complaints and unwilling to compromise. Consequently, Congress was wary to vest significant power in the executive. As Patrick Henry, a staunch opponent of a more powerful central government, stated, the Constitution “squints towards monarchy” and added “your president may easily become king”.

However, the delegates also knew from their experience with the Articles of Confederation that the lack of a single head of state created its own issues, especially in dealing with foreign affairs. To truly be a participant on the world stage, they had to remedy this problem.

The office finally created by Congress in Article II of the Constitution required that the President “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” and “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution”. The president was also named as the military commander-in-chief and chief diplomat.

There was even a debate regarding how George Washington, who was inaugurated as President on March 4, 1789, was to be addressed. John Adams, who was the Vice President, thought the title should be somewhat regal and on par with what other heads of state were called. Adams scoffed that even fire companies and cricket clubs had “presidents” and that Washington should be addressed as “His Majesty the President” or “His Highness, the President of the United States and Protector of the Rights of the Same”. That is a mouthful!

Over the years, the power of the President has grown along with the power of the Federal government. This is especially seen with executive orders. Although all Presidents except for William Henry Harrison have issued executive orders, the practice has grown over time. Prior to the Civil War, only one President (Franklin Pierce) issued more than 20 executive orders during their term of office.

Now it is common for a President to issue over 200 or more executive orders while in the White House. While President Reagan issued 381 and President Obama issued 276, the all-time record holder by far is President Franklin Roosevelt at 3,522 executive orders followed by Woodrow Wilson at 1,803.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why does the debate over executive powers and what our Founders ultimately designed for this office matter to us today? In some ways, the office of the President and the powers vested in it was the most important addition to the new Constitution. This office created the leader of our nation, that single star to guide us through troubled times. Try to imagine our country surviving its formative years without that indispensable man, George Washington, or the Civil War without Lincoln’s guiding hand. While not all have been up to the challenge, the good ones have been priceless.

SUGGESTED READING

One of the best books on the evolution of the Presidency is John Yoo’s “Crisis and Command: The History of Executive Power from George Washington to George W. Bush”. Yoo points out that cries of executive over-reach have been heard since Washington and Jefferson were President, and that each national crisis only serves to increase the power of the office. An excellent read.

PLACES TO VISIT

The White House, home of the President, is a must see for all Americans. The beauty and grandeur of the rooms and the knowledge of what has occurred in that historic building fills visitors with a sense of awe. Be aware you may need to apply for a ticket to take the self-guided tour.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

The opening phrase of the preamble, “We the People,” spoke volumes regarding upon whose authority the Constitution rested and suggested the unanimity of country and purpose that this new Constitution would create. It was written by Gouverneur Morris, a delegate from New York, and his eloquent words speak for themselves.