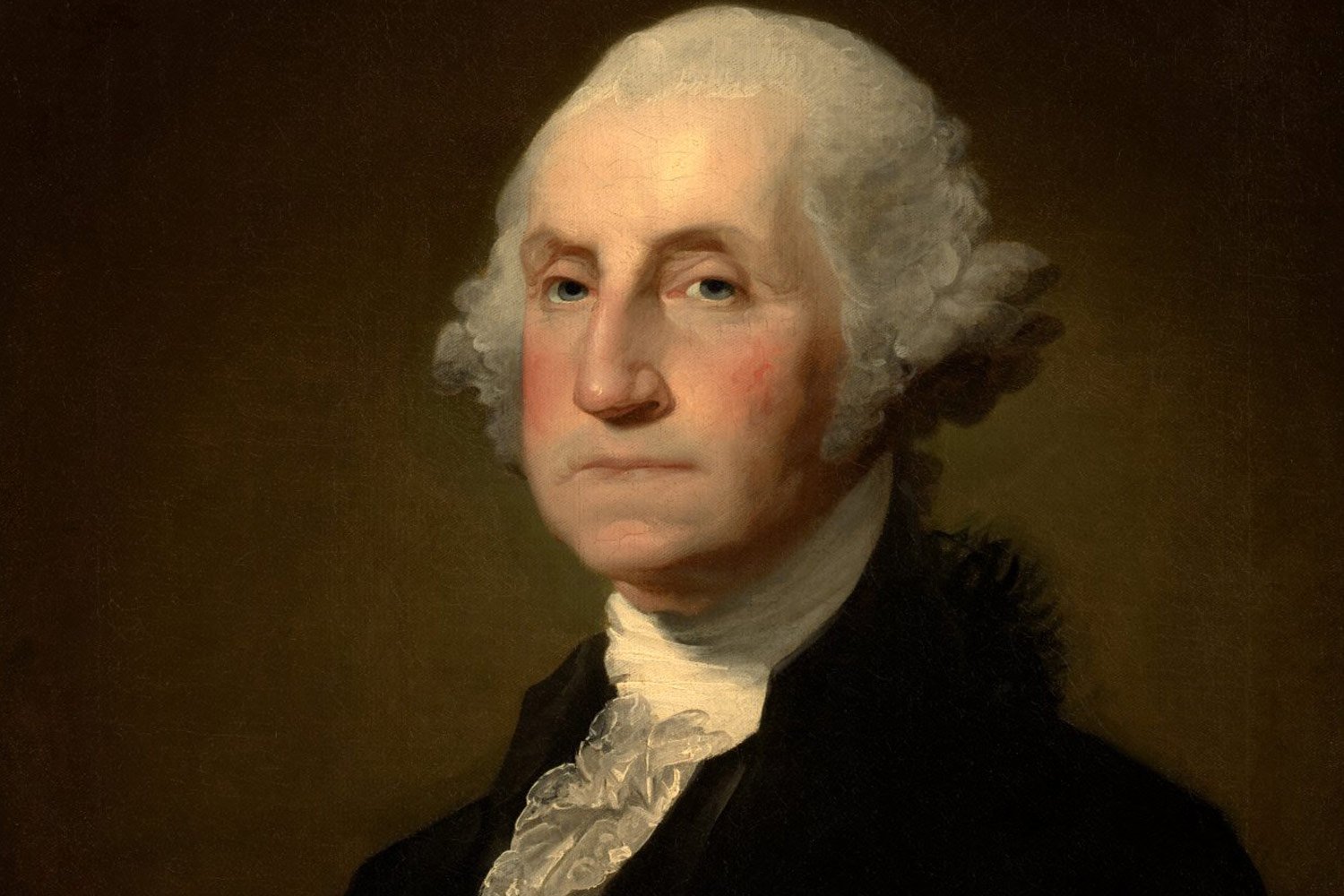

George Washington and the Continental Army’s Path to Victory

General Washington formally took field command of the Continental Army surrounding Boston on July 3, 1775. He immediately began to organize and train the troops and his natural aggressiveness was soon on display.

He quickly dispatched General Henry Knox to Fort Ticonderoga to bring siege guns captured there in May 1775 to Boston to use against the British. Once the heavy guns were in place on Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston Harbor, the English commander, General William Howe evacuated the town on March 17, 1776. We had achieved our first great victory.

The British Army eventually ended up in New York, but Washington had anticipated that move and he was there to greet them when they arrived. Washington’s army was outnumbered and outgeneraled and lost both Long Island and Manhattan to the English over the course of about two months in late summer 1776.

Retreating through New Jersey towards Philadelphia, Washington and the remnants of the army crossed into Pennsylvania in December 1776. At that point, General Washington’s command had dwindled down to roughly 4,000 poorly clad and poorly fed men. Thinking the end was near, General Howe retired to the warmth of his house in New York City and placed his soldiers in winter quarters. But Howe did not know George Washington.

Seizing this opportunity, Washington famously crossed the Delaware River on Christmas day and decisively defeated a contingent of Hessians at Trenton, New Jersey. Just ten days later, on January 3, 1777, he soundly defeated a regiment of British regulars at Princeton, this time saving the day with an incredibly brave charge into the fray to rally the troops.

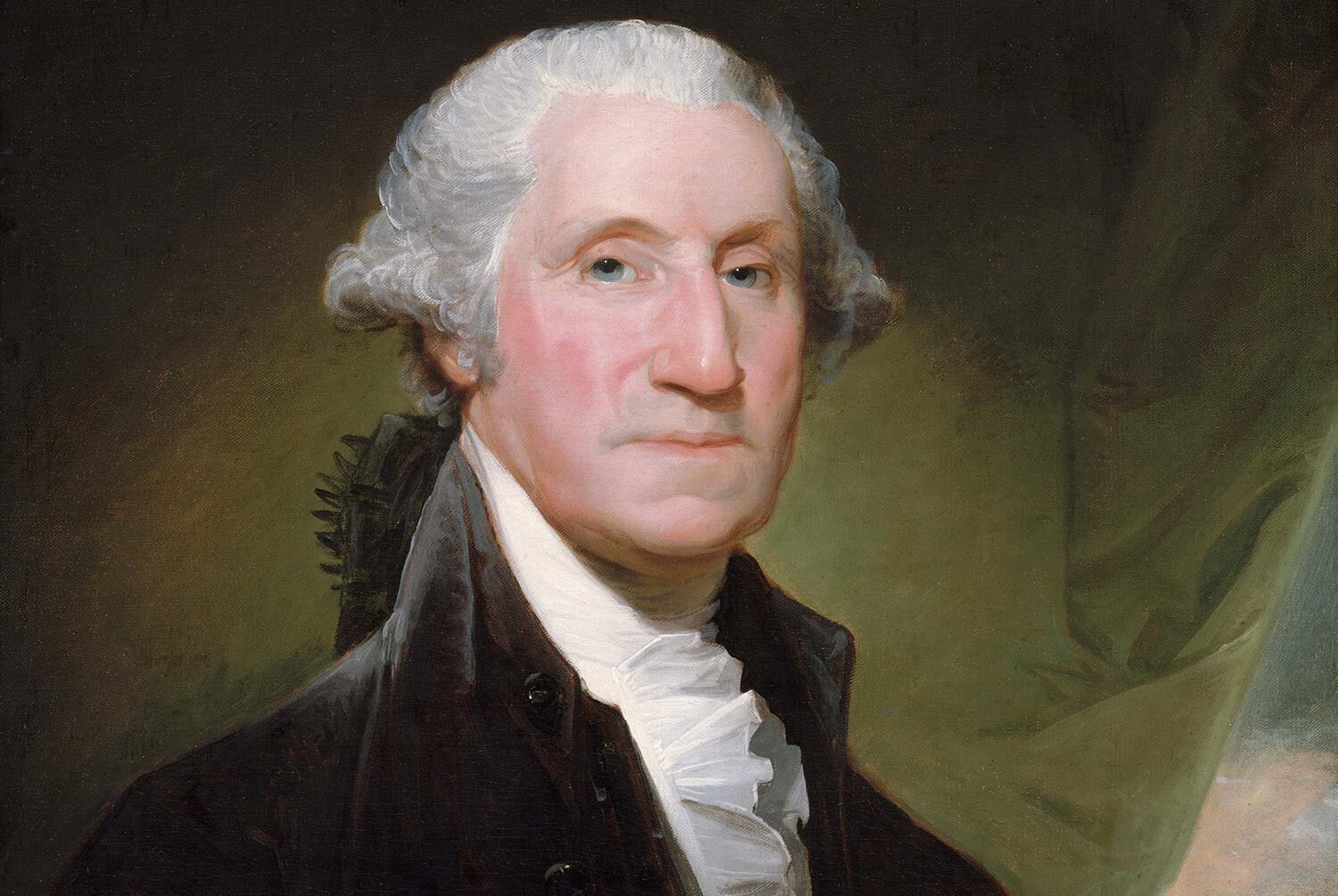

Washington’s heroic perseverance and incredible will had kept the army together as a formidable fighting force, and his daring and field generalship in these two victories at the close of this first campaign saved the American cause.

In the spring, Howe decided to attack Philadelphia, the largest city in the colonies and where the Continental Congress was meeting. Washington, aggressive as ever, moved to intercept him but was defeated at Brandywine and again at Germantown, and the British occupied Philadelphia on September 26, 1777.

Although Washington’s Continentals lost these two battles, they stood up to the Redcoats like never before, a fact both sides recognized. More importantly, Washington had once again held the army together in a second lengthy campaign.

In December 1777, General Washington moved his ragged army into winter quarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, just 20 miles outside of the city. While the British refreshed and retooled and stayed warm, the Americans shivered and starved in crude wood huts.

That terrible winter, thanks to a bickering and seemingly indifferent Congress, about 2,500 of the 10,000 troops died of exposure and hunger. On December 22, 1777, Washington wrote to Henry Laurens, then President of the Continental Congress, “unless more vigorous exertions and better regulations take place in that line (supplies) and immediately, this army must dissolve.”

As befitting the great commander that he was, General Washington remained at Valley Forge with his troops throughout this long winter. Without General Washington’s entreaties to Congress and his steadfast leadership with the soldiers, the Army would never have survived the ordeal. But we did have Washington, and we did survive.

In 1778, hearing of our Treaty of Alliance with France, Sir Henry Clinton, the new British commander, evacuated Philadelphia on June 18 and moved his army back to New York. Washington was not content to simply let him go and attacked the rear guard at Monmouth Courthouse, New Jersey on June 28, 1778. Although the battle started poorly for the Americans, Washington again saved the day and the fight ended in a draw.

This engagement would prove to be the last major battle in the north of the American Revolution. By July, the British were back in New York City and the Continental Army was back in White Plains, New York. Impressively, after this grueling two-year campaign, Washington’s troops had essentially fought the most formidable army and navy in the world to a stalemate.

The focus of the war then shifted to the south from 1779-1781, but Clinton and his army remained in New York and Washington was forced to stay close by to keep an eye on them. Then, in the fall of 1780, the French finally sent a 5,000-man contingent to aid the Americans.

In August 1781, when a British force under Lord Cornwallis headed towards the James Peninsula in Virginia, Washington saw an opportunity. He quickly moved the Continental Army and our French allies to confront this force. While maintaining a ruse to fool Clinton into thinking the main Continental Army was still nearby, Washington headed south. The result was the incredible victory and capture of the entire army of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Although some fighting continued for another year, the American Revolution was essentially over. Washington had done what seemed unthinkable just a few short years before. He had defeated the British army.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why should the accomplishments of General Washington and the Continental Army matter to us today? In short, General Washington and the Continental Army gave us our independence from England and allowed our great country to be born. All the inspirational words in the Declaration of Independence and all the wishes of our political leaders would not have mounted to anything more than words if our brave soldiers had not been victorious. All Americans are indebted to these fine men for their efforts.

SUGGESTED READING

1776 by David McCullough is one of the most enjoyable books to read about the struggles General Washington had to overcome early in the American Revolution. Published in 2005, it is highly recommended.

PLACES TO VISIT

The American Revolution Museum at Yorktown is a wonderful place to visit. Operated by the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, it has a fantastic museum and numerous outdoor exhibits.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.