The Siege of Ninety Six

In the spring of 1781, American forces under General Nathanael Greene rolled up the British garrisons in the interior of the Carolinas one by one. The last British holdout was the fortified town of Ninety Six, in the foothills of western South Carolina. Greene arrived on the scene with 1,000 men and commenced the siege of Ninety Six on May 22.

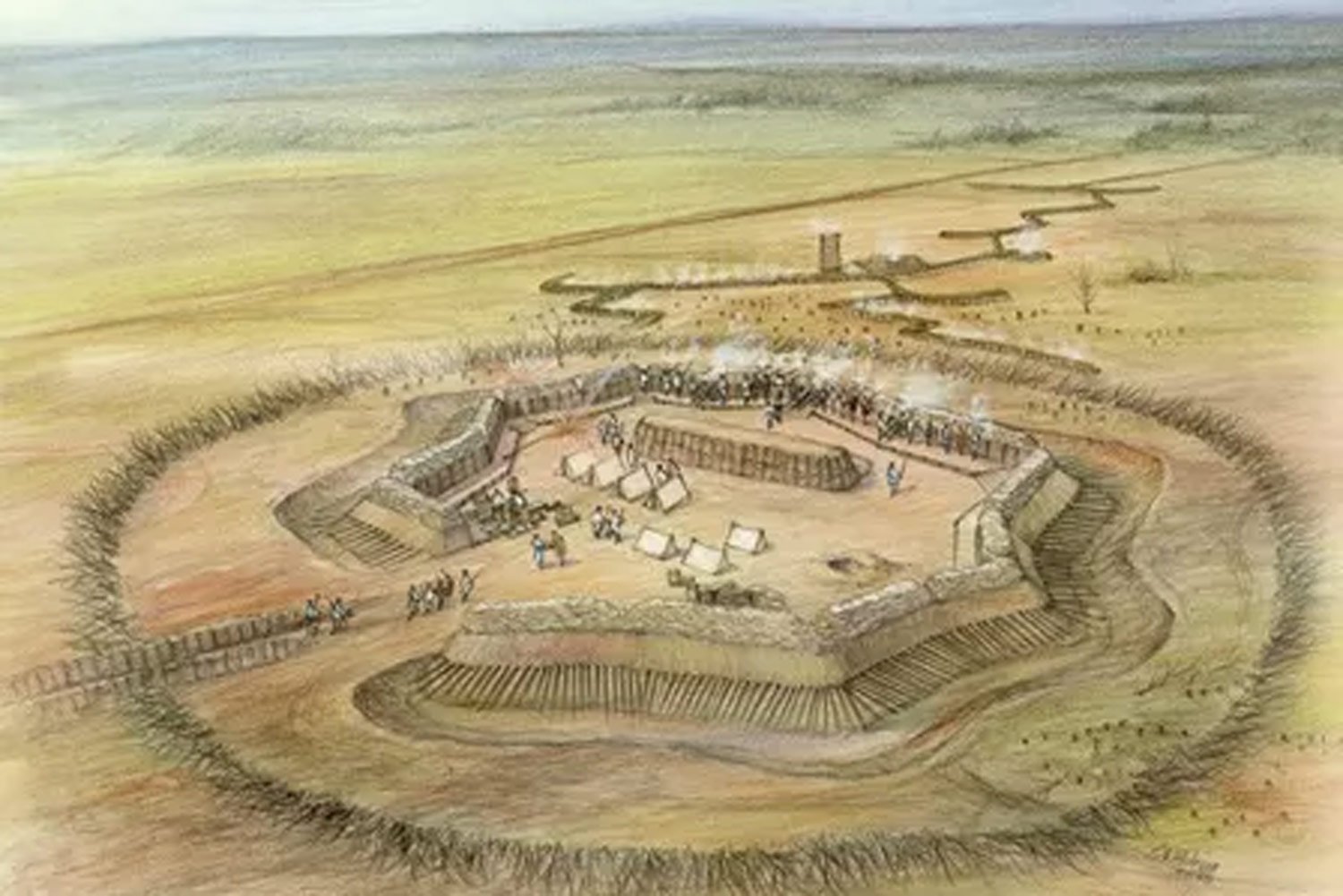

Although there is some uncertainty regarding how the town got its name, the generally accepted story is that the town is ninety-six miles from the principal Cherokee town of Keowee. The British had occupied the area since 1780 and considered it a strategic location due to the lush farm country in which it was located. Since their arrival, the British had greatly strengthened the town, building a palisaded wall with a deep moat and abatis (sharpened wooden stakes facing outward) around Ninety Six.

The fort’s commander was Colonel John Harris Cruger, a Loyalist from New York, who led 550 experienced men, mostly from Delancey’s Brigade. Cruger was from a long established and prosperous merchant family in New York and had been on the Governor’s Royal Council when the war began. One of the many talented men who remained loyal to the Crown, Cruger performed admirably at Savannah, Charleston, and the Battle of Camden. After the war, with his home and land confiscated by the Patriots, Cruger sailed to England and spent his remaining days there.

In any event, Cruger’s men built an earthen star fort to defend the town and it was here that Greene focused his efforts. The main task of reducing the fort fell to Colonel Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a Polish officer, who had been serving in the Continental Army since his arrival in North America in 1776.

Karl Gottlieb Schweikart. “Portrait of Tadeusz Kosciuszko.” Wikimedia.

Often called the Engineer of the Revolution, Kosciuszko served ably in many campaigns during the war. At Saratoga, his obstructions and barricades erected over the British Army’s route of march slowed its advance and helped to starve Burgoyne’s army into submission. At Fortress West Point, Kosciuszko devised an almost impregnable line of defenses at this key bastion on the Hudson River. In 1780, General George Washington granted Colonel Kosciuszko’s request to transfer to combat duty with the Southern Army.

Kosciuszko immediately began to dig parallel trenches to get closer to the star fort, so the Americans could employ their four cannons at point blank range. He also had the men erect a thirty foot tower from which sharpshooters could shoot over the fort’s eighteen foot high walls, making life perilous inside the fort. Cruger made several sorties from the fort to drive off the Americans but to no avail.

On June 12, with the end in sight for Cruger and his men, a lone rider made it through the American lines and raced into the fort with word that 2,000 men under Lord Francis Rawdon was on the way from Charleston, two hundred miles away. Cruger now resolved to dig in and wait for this relief force rather than capitulate.

The rank and file under Greene’s command, not wanting to leave without one last try at taking the fort, pressured Greene into launching an assault against his better judgment. On the night of June 18, the Americans attacked the stout palisaded walls but were hit with a withering fire from the fort. At a critical moment, Cruger counter-attacked and, in fierce hand-to-hand fighting, mostly using bayonets and muskets as clubs, beat off the attackers.

The next day, with Rawdon only thirty miles away, Greene made the painful decision to raise the siege and once again retreat northward across the Broad River. The siege and the assault had been costly to the Americans who lost 185 men killed and wounded, almost twenty percent of Greene’s force, while Cruger suffered 100 casualties.

The victory was a hollow one for Rawdon and Cruger who recognized that Ninety Six was simply too far from Charleston to be easily supported. On July 3, the fort and town were burned to the ground and abandoned by the British, with Rawdon deciding to relocate the garrison to Orangeburg and then to Charleston. Greene followed and took up a position in a string of hills northwest of Charleston called the High Hills of Santee, named after the nearby Santee River.

With his men resting and the British hunkered down in Charleston, Greene had a chance to reflect on his significant accomplishments in 1781. In seven months, Greene had driven the British from the interior of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. He had done this without winning a major battle, the one exception being Daniel Morgan’s victory at Cowpens in January. Despite his success, Greene was still subject to criticism from some members of Congress for his habit of retreating.

In a letter on July 18 to his friend Jeremiah Wadsworth, Greene wrote, “There are few Generals who have run oftener, or more lustily, than I have done. But I have taken care not to run too far; and commonly have run as fast forward as backward.” Importantly, General Washington recognized Greene’s accomplishments writing,” The difficulties you daily encounter and surmount with your small force add to your reputation.”

Next week, we will discuss the final battles in the South and the legacy of Nathanael Greene. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Commodore Edward Preble assembled his considerable American fleet just outside Tripoli harbor in August 1804, determined to punish the city and its corsairs, and force Yusuf Karamanli, the Dey of Tripoli, to sue for peace.