Nathanael Greene Retakes the Carolinas

When General Nathanael Greene crossed the Dan River and escaped to Virginia on February 14, 1781, Lord Charles Cornwallis’ British army controlled all of North Carolina, and most of South Carolina and Georgia. Within the short span of seven weeks, all that would change.

Two days after the fight at Guilford Courthouse, Cornwallis faced the reality that his strategy to roll up the southern colonies one at a time had failed. With over 400 wounded soldiers to care for and little food to be found, Cornwallis made the painful decision to give up the interior of the Carolinas and retreat to his supply base at the North Carolina port city of Wilmington. In Cornwallis’ wake, without the presence of a strong British strike force, the Loyalists in the region, recognizing they had no chance at success, melted away.

Encumbered with the wounded, the two-hundred-mile march took three agonizing weeks to complete, finally reaching the friendly confines of Wilmington on April 7. Greene and his Continentals trailed Cornwallis the whole long way but at a wary distance, looking for an opportunity to strike Cornwallis’ suffering army but not willing to “risk too much.”

On April 24, after recuperating for three weeks, Lord Charles Cornwallis and 2,000 battle-hardened veterans, the flower of the British forces in the south, bid a bitter adieu to the Carolinas and headed to Virginia. Greene’s strategy to wear down and frustrate Cornwallis had worked as his Lordship wrote he was “quite tired of marching about the country in quest of adventures.” Cornwallis was hoping for better outcomes in Virginia but in six short months he would suffer the greatest embarrassment of his professional career when he surrendered to General George Washington at Yorktown.

Cornwallis turned over the command of the Carolinas to Colonel Lord Francis Rawdon, youthful at twenty-six but a very competent officer who had fought bravely at Bunker Hill, Monmouth, and other smaller engagements. Rawdon was left to oversee several outposts spread in an arch across South Carolina but that were now more of a liability than an asset. They all had to be garrisoned which spread out the remaining British forces but none of them were mutually supporting. The shrewd Greene recognized this fatal flaw and immediately began to reconquer the Carolinas one piece at a time.

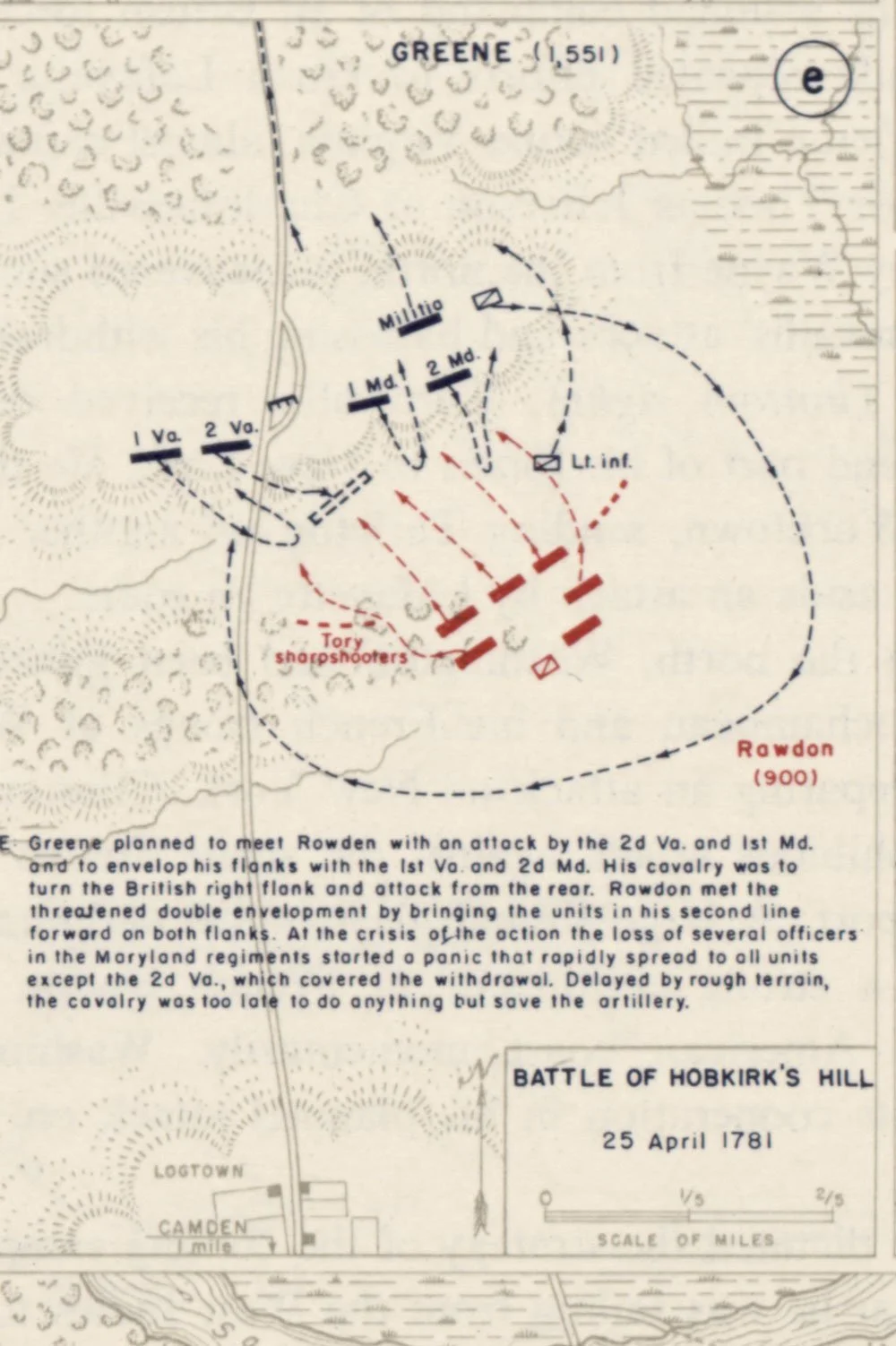

“Revolutionary War - Camden, Cowpens, Guilford, Hobkirk's Hill, Eutaw Springs.” Library of Congress.

The first to fall was Fort Watson on April 23 when it was captured by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Lee and Francis Marion, better known as the Swamp Fox for his unmatched ability to strike and inflict damage on British outposts and then elude pursuers. Interestingly, Marion, considered one of the fathers of irregular warfare, earned his nickname from a comment from one of his primary adversaries, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. After chasing Marion for twenty-six miles through a dense swamp, Tarleton remarked, “as for the old fox, the Devil himself could not catch him.”

Greene meanwhile had approached Camden with the hopes of surprising Rawdon and taking this critical supply post. Instead, it was Rawdon who caught Greene unawares and hit the Americans as they were eating their breakfast. Greene quickly recovered but, due to battlefield errors by Colonel John Ganby, the Americans were defeated once again at the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill on April 25.

It was after this loss, that Greene famously summarized his efforts to date in the south: “We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.” What Greene left unsaid was that his war of attrition had broken the back of the British and thanks to Greene’s leadership and incredible perseverance, he had succeeded where others had failed.

While Greene’s army lost the major engagements, his subordinates were enjoying considerable success elsewhere. On May 11, South Carolina militia General Thomas Sumter, nicknamed the Gamecock, captured Orangeburg, just south of Camden. On May 12, Lee and Francis captured Fort Motte and its 150-man garrison, and, the next morning, Greene sent Lee to capture Fort Granby which Lee did that same day.

Greene then sent Lee, arguably the Continental Army’s most capable cavalry commander and the future father of Civil War icon Robert E. Lee, to assist General Andrew Pickens, an experienced leader of South Carolina militiamen, at the siege of Augusta, Georgia. This important town on the Savannah River and its garrison of 350-Loyalists and 300 Creek Indians would surrender on June 5.

Meanwhile Marion was sent to harass Rawdon who was still at Camden. The Swamp Fox became a nuisance Rawdon could not handle and Rawdon abandoned Camden on May 9 and the important post at Georgetown on May 29 and retired both garrisons closer to Charleston.

Incredibly, in the span of little more than a month, Greene’s command had captured four forts and forced the abandonment of two more. Moreover, the southern Continental Army, given up as a lost entity prior to Greene’s arrival just six months before, had captured almost 1,000 prisoners and reduced the British foothold in the south to the port cities of Savannah, Charleston and Wilmington and the fort at Ninety Six. It was to this fort that Greene next turned his attention.

Next week, we will discuss the siege of Ninety Six. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

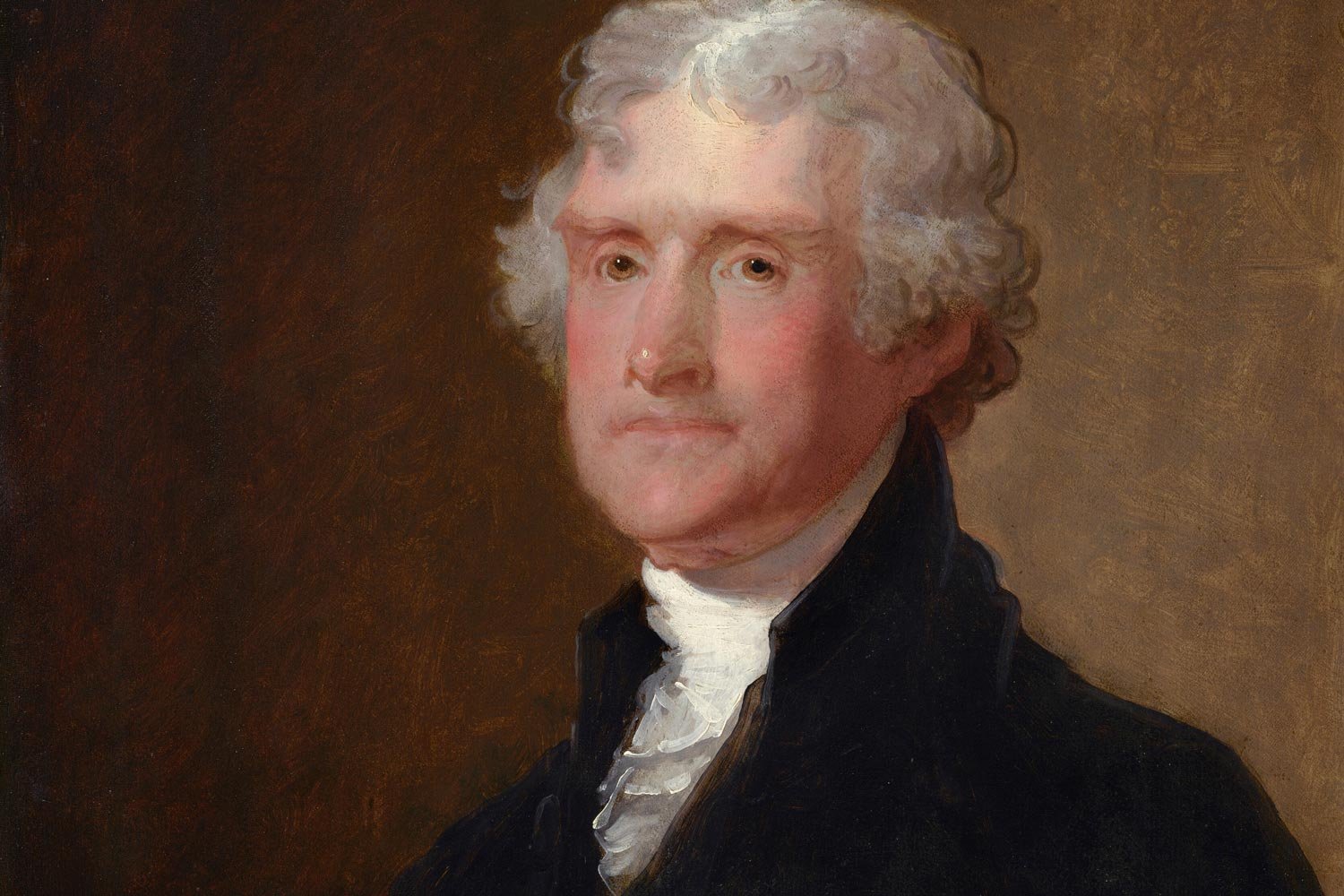

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.