The Battle of Guilford Courthouse

Following the successful conclusion of the Race to the Dan, General Nathanael Greene and his southern army was safe for the moment from the British troops under Lord Charles Cornwallis just across the river. Due to a lack of supplies in the area, Cornwallis retreated to Hillsboro, about sixty miles southeast, to get refitted. By late February, Greene had received reinforcements, recrossed the Dan, and had the American army back in North Carolina.

Greene decided that the time had come to finally confront Cornwallis in a pitched battle and selected Guilford Courthouse, in Guilford County, as the spot. At this point, Greene had roughly 4,000 men under his command, but that number was a bit misleading as 2,700 were militiamen and only 1,300 were Continental soldiers. Meanwhile, Cornwallis’s army had dwindled to 1,900 Redcoats, but all were seasoned professionals.

In one vital area, the opposing forces had finally achieved parity; both were tired and hungry with little to eat and no sign of any provisions coming their way. Moreover, because Cornwallis had burned all excess baggage early in his pursuit of Greene, the Brits had been exposed to the elements each night for seven weeks and ammunition was running low. Cornwallis desperately needed a fight and a victory to justify his last three months of chasing Greene across the North Carolina countryside.

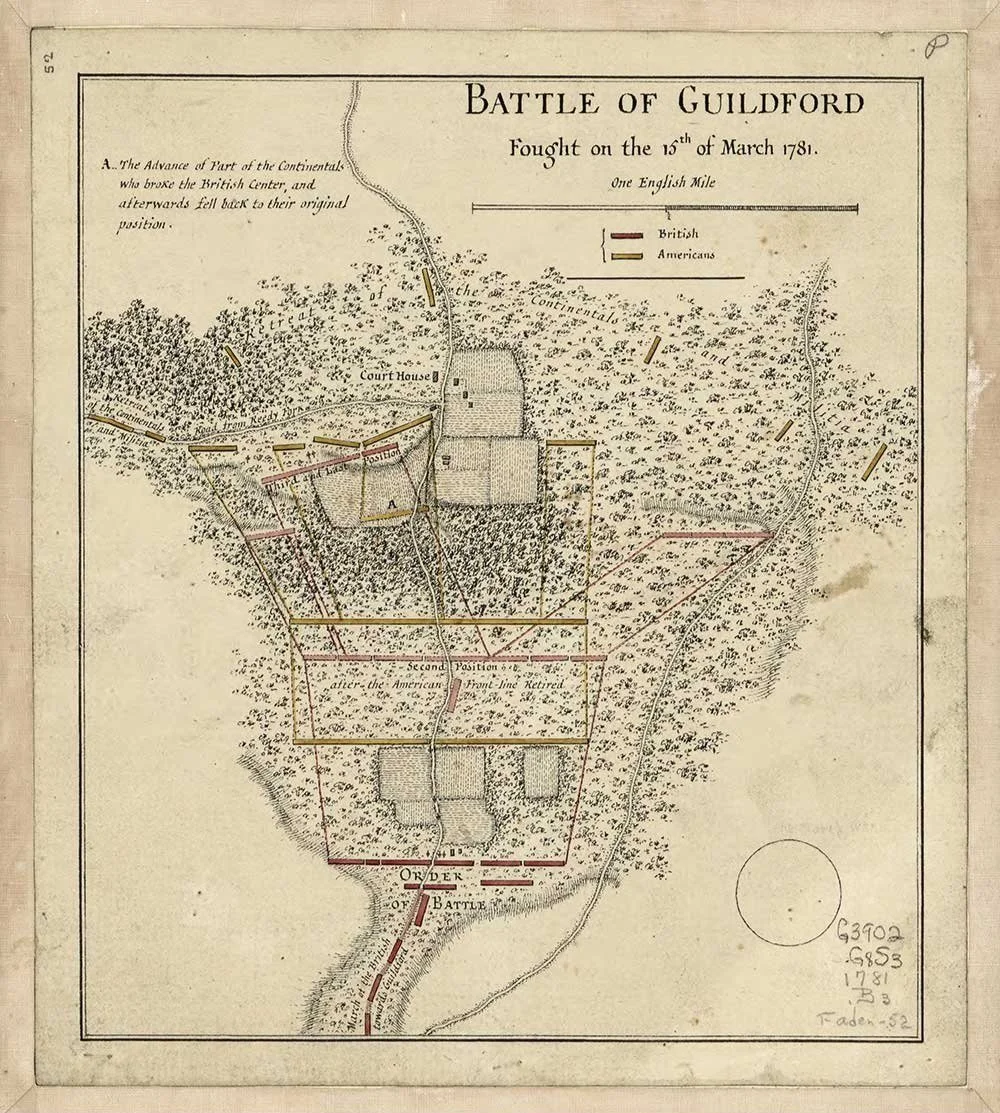

Greene had previously reconnoitered the area around Guilford Courthouse and was familiar with the landscape and terrain surrounding it. He chose a series of fields about half a mile west of the courthouse along Little Horseshoe Creek to make his stand.

With Daniel Morgan’s brilliant victory at Cowpens fresh in Greene’s mind, Greene positioned his troops in the same manner employed by Morgan at that January battle. Greene placed the 1,000 North Carolina militia in the front rank along a fence line and asked them to fire two shots and then peel back to the rear.

About four hundred yards behind them, Greene placed the Virginia militia, numbering 1,700 men, but interspersed reliable Continentals amongst them. Finally, another four hundred yards behind the Virginians stood 1,400 tough Marylander Continentals under the leadership of Colonels Otho Williams and John Eager Howard, two of the finest commanders in the army.

Morgan, following the operations from his home in Frederick County, Virginia, wrote some sage advice to Greene: “If they (the militia) fight, you will beat Cornwallis; if not, he will beat you and perhaps cut your regulars to pieces. Put the militia in the center with some picked troops in the rear with orders to shoot the first man that runs.”

On March 15, a bright sunny day, Cornwallis started his men marching before dawn and did not stop for breakfast. The tired, hungry Brits arrived on the battlefield around noon and Cornwallis immediately commenced the attack. As expected, the front-rank North Carolina militiamen fired a few shots and then some moved to the rear while many simply headed for home.

“Battle of Guildford fought on the 15th of March 1781.” Library of Congress.

The second line of Virginians held their position and fought well for about thirty minutes before they too broke and fled. So far, the battle was shaping up to be another Cowpens as the British soldiers had charged across several hundred yards of fields and broken two lines of American militiamen.

Cornwallis now threw his men forward at the final American line and a bloody melee ensued, with the Americans giving as good as they got. With Continentals under Colonel Howard threatening his flank and the fight hanging in the balance, Cornwallis took a very unorthodox step: he fired into his own men.

With hand-to-hand fighting raging just in front of him, Cornwallis ordered his artillery to load grapeshot and fire point blank into the mass, Brits and Americans alike. Questioned by his second-in-command, General Charles O’Hara, Cornwallis informed him he had no choice. Although the cannon fire killed as many British soldiers as American, it had its intended effect and broke up the American attack.

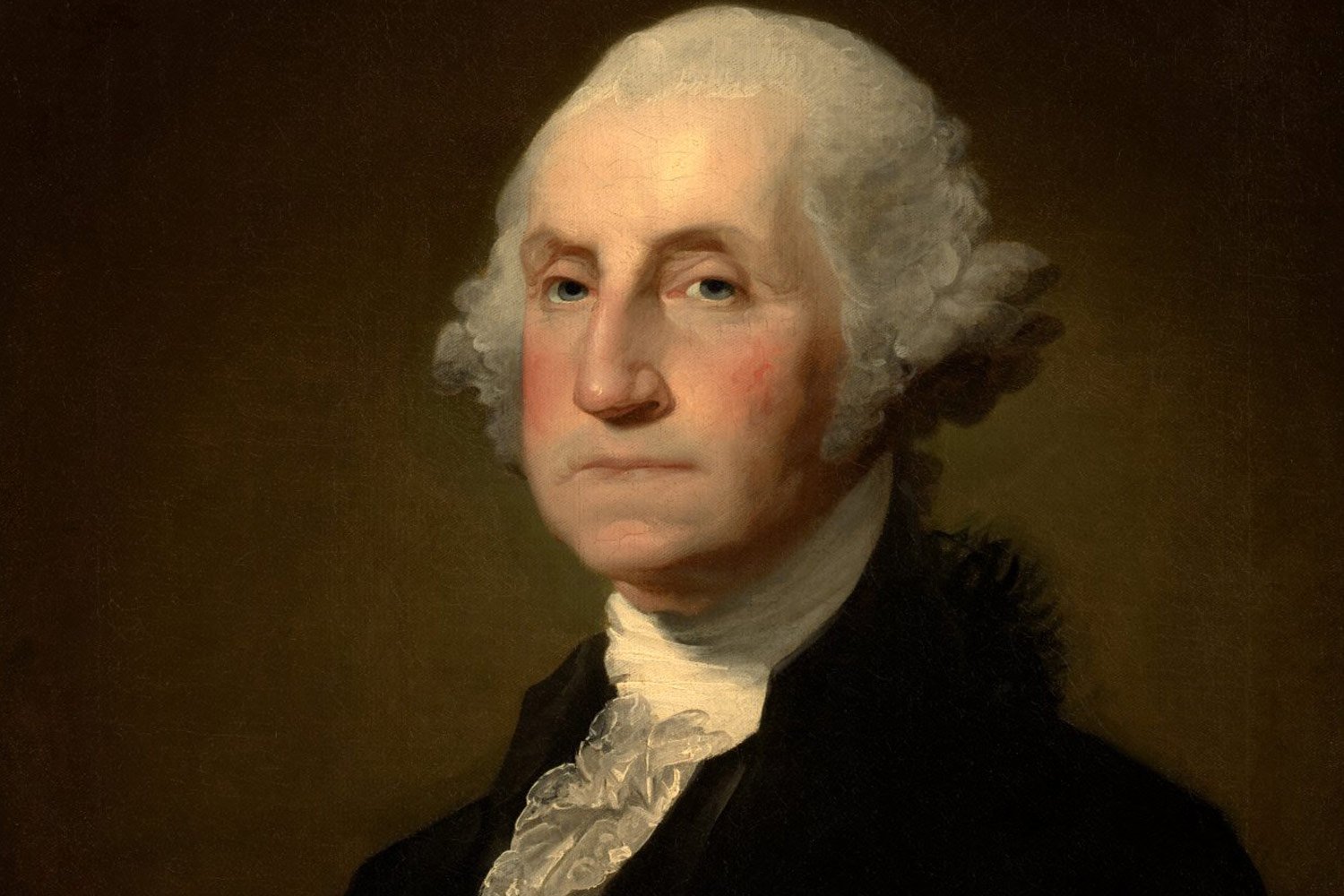

Rather than risk a total defeat, Greene ordered his men to retreat down the Reedy Creek Road to the Speedwell Iron Works, and there he set up camp and his defenses. As Greene informed General George Washington, he knew he had greatly damaged Cornwallis and did not want to “risk too much.” As for Cornwallis, his men were in no shape to pursue and they remained at Guilford for two days.

While the Americans suffered 260 casualties, Cornwallis lost 500 killed and wounded, one quarter of his entire force. Naturally, Cornwallis wrote to England that he had achieved a great victory, but the ministers were not buying it. MP Charles Fox remarked, “Another such victory would ruin the British Army.”

With a long train of wounded men and little to eat, Cornwallis had no choice but to leave the mid-state region of North Carolina and retreat to the port city of Wilmington to be resupplied. His grand plan to roll up the southern colonies one at a time had utterly failed. Cornwallis learned as had Burgoyne at Saratoga that the vastness of North America was simply unconquerable in the face of a determined enemy.

Next week, we will discuss General Nathanael Greene retaking the south. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

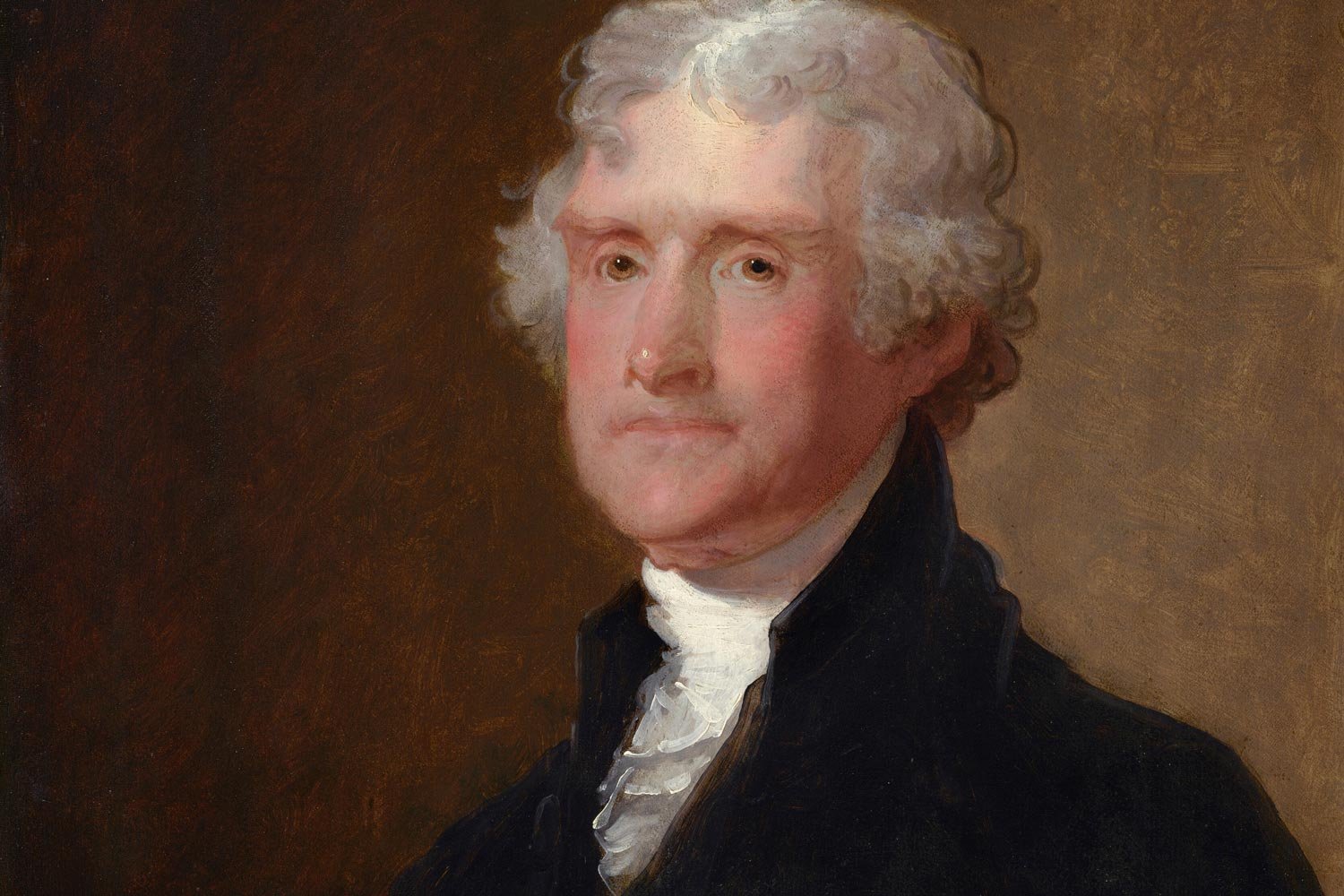

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.