The Race to the Dan

The Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, was a great victory for Daniel Morgan and his army of Continentals and militiamen. They had virtually annihilated Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s famed British Legion, but Morgan’s contingent was in a dangerous position, with a larger British force under Lord Charles Cornwallis only twenty-five miles away. The race was now on to get to a place of safety.

Within a few hours of the conclusion of the battle, Morgan had his men and prisoners on the move. Over the years, Morgan had become adept at rapid marches, and, in five days, Morgan marched his force 100 miles over deplorable roads and crossed two rivers, the Broad River on January 17 and the Catawba on January 24. Once across the Catawba, Morgan set up camp and was joined there by Major General Nathanael Greene, the commander of the southern Continental Army.

Morgan’s long-aching back, worn down from years of hard use, finally gave out and he was forced to retire once more to his home in Frederick County, Virginia. The Old Wagoner, as General Morgan referred to himself because of his first occupation as a wagon driver, would be forced to sit out the rest of the war. But Morgan had done his part to help the American cause and had proven himself to be one of the Continental Army’s greatest battlefield commanders.

After the war, Morgan continued to serve the country to which he was so devoted. In 1794, Morgan was recalled to active duty to help suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, with instructions coming from President Washington to raise a militia and join him in the field. Although the rebellious western Pennsylvanians dispersed at the approach of the army, Morgan was asked to stay and oversee affairs in the region, finally heading home in May 1795.

The following year, the Old Wagoner became Congressman Daniel Morgan in the United States House of Representatives, serving for one term. This stalwart patriot who had marched to Quebec, fought at Saratoga, and resoundingly crushed the British at Cowpens died at his daughter’s home in Winchester in 1802.

In any event, Cornwallis finally came up and forced his way across the Catawba on January 31. The retreat of the Americans continued, and, on February 2, they crossed the Yadkin River, wisely collecting all boats along the river, forcing Cornwallis to move west in search of a ford.

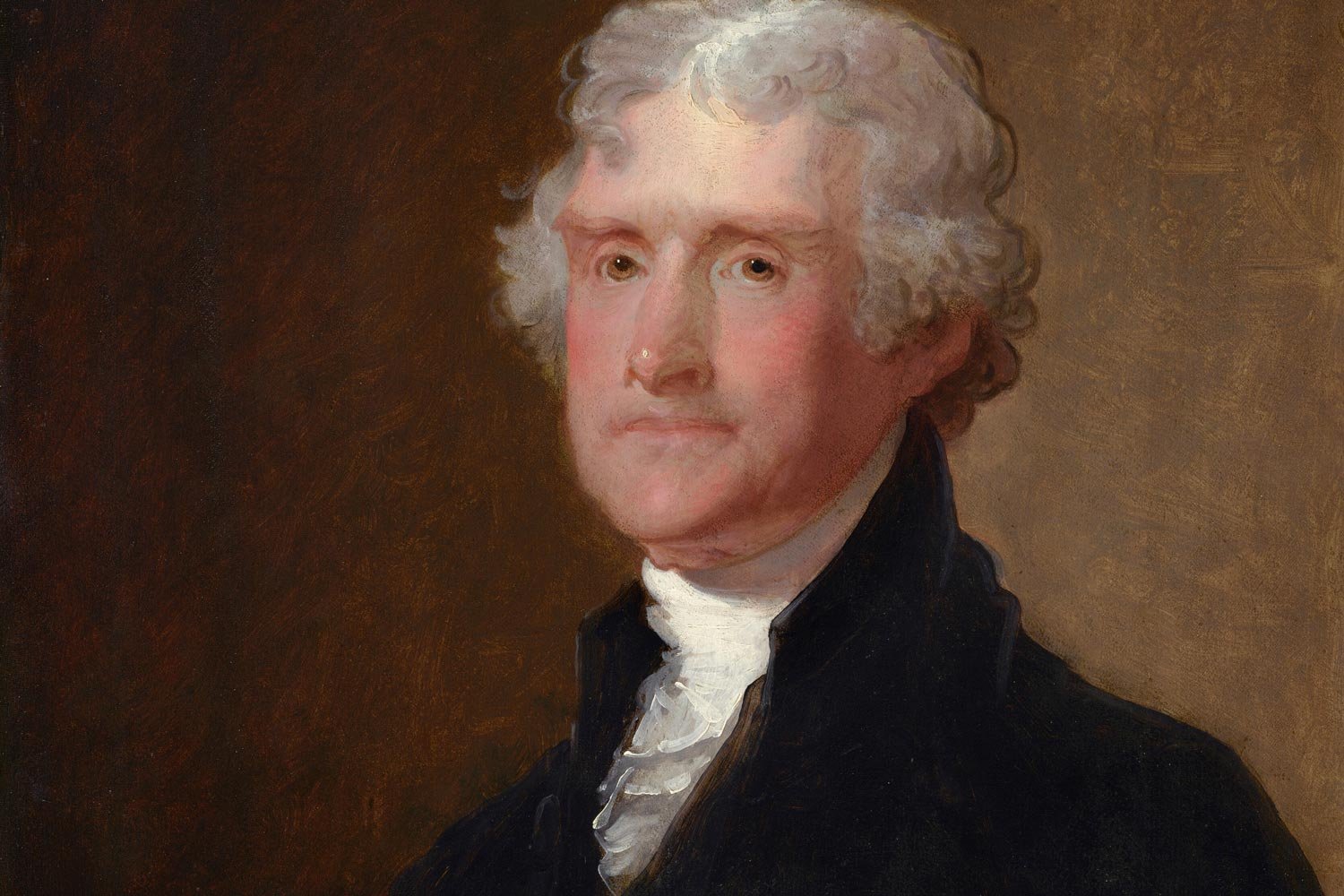

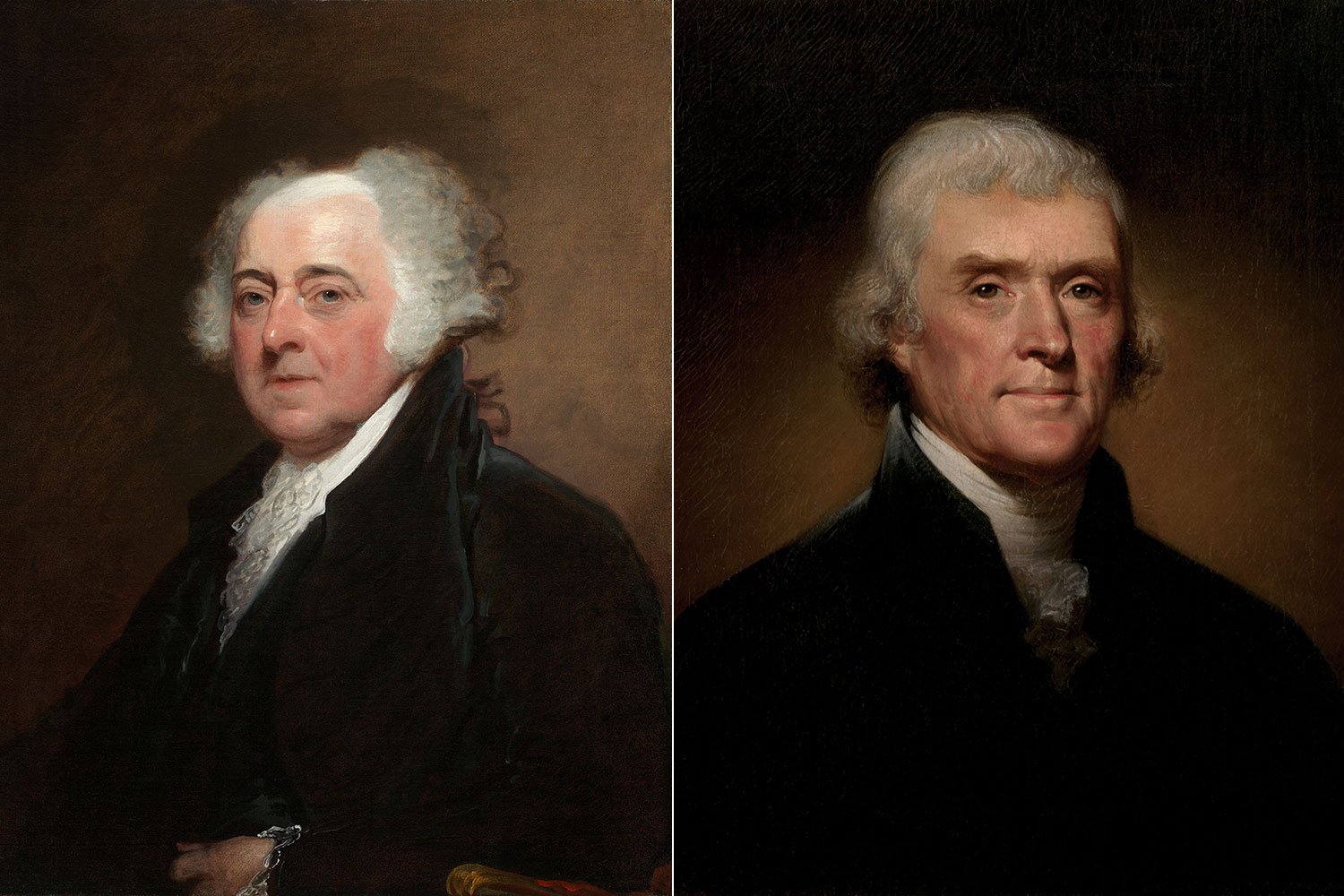

“Daniel Morgan.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

To speed his pursuit, Cornwallis burned all excess wagons and baggage including tossing his own tent into the flames and destroyed numerous casks of rum much to his troop’s disappointment. By February 10, Cornwallis and his 2,500 battle-hardened veterans were only thirty-five miles away from the American army and closing fast. With the Dan River a full three-day march away and laden with supply wagons, Greene knew he would lose the race if he did not somehow gain time.

Greene decided to split his force, sending Colonel Otho Williams and a 700-man light corps as a decoy on a different route hoping to pull Cornwallis away from the main army. Cornwallis took the bait and followed Williams’s trail, while Greene and the bulk of the men moved north towards the Dan. Thinking ahead, Greene ordered Colonel Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a Polish officer, and Lieutenant Colonel Edward Carrington, Greene’s quartermaster, to round up all watercraft within thirty miles of the Dan and assemble them at Irwin’s Ferry.

Greene got the main army over the Dan the afternoon of February 14 and sent a messenger to Williams that “The troops are all across, the stage is clear,” and to make his way to Irwin’s Ferry pronto. Williams and his troops covered the final forty miles in just sixteen hours, an incredible feat, and crossed the fast-flowing Dan just three hours ahead of the British.

When the men made camp that night, they got their first good night’s sleep since the march began. With one cold rainy day after another and scarcely anything to eat for weeks, many were at their breaking point. Greene noted in a report to General Washington that many men were barefoot and “several hundreds of the Soldiers tracking the ground with their bloody feet.”

Although Cornwallis had failed to destroy Greene’s army, he now held North Carolina unopposed. The problem was that his force was worn down as well from the long chase and too far from its supply base to remain in the vicinity. Consequently, Cornwallis withdrew to Hillsboro, about sixty miles away, and, in late February, Greene reentered North Carolina.

General Nathanael Greene’s series of brilliant maneuvers to remain one step ahead of the British is known as the Race to the Dan. All told, the Americans covered over 200 miles on muddy, barely passable roads through almost uninhabited country and forded 4 large rivers. They did this with just the barest of provisions and, in most cases, without adequate shoes or clothing. Greene’s leadership was inspirational and his superbly executed tactical retreat, one of the finest in the annals of American warfare, allowed the American southern army to live to fight another day.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.