Daniel Morgan’s Masterpiece at Cowpens

Daniel Morgan came out of his self-imposed retirement and returned to the Continental Army near Hillsborough, North Carolina in late September 1780. He felt he could no longer sit on the sidelines while his country was at war. In December, Major General Nathanael Greene sent newly promoted Brigadier General Morgan and 600 men west to threaten British outposts in western SC.

When morning broke on January 17, 1781, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan arranged his Continentals and militiamen into lines of battle in a field in western South Carolina known as Hannah’s Cowpens, so named for the man who grazed his cattle there. Across the pasture was the feared British Legion under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, a cavalryman who had known nothing but success over American troops since his arrival in 1776. That was about to change.

Morgan had been advised by General Greene to avoid a pitched battle unless certain of victory. Above all else, Morgan was expected to preserve his small army. But with the Broad River about six miles to his rear and the water running high, Morgan felt the time had come to stop retreating and have it out with Tarleton.

Because militiamen were continually coming into the American camp, some as late as the night before the battle, accounts vary as to Morgan’s headcount. He probably had about 1,200 men of which 450 were experienced Continentals from Maryland and Delaware. By comparison, Tarleton had about 1,200 men under his command, most of whom were seasoned veterans.

Morgan knew Tarleton to be impetuous, ever aggressive, and contemptuous of American troops. He suspected Tarleton would arrive on the field and without delay launch a frontal assault, expecting Morgan’s men to flee when faced with the British Legion bearing down on them.

Consequently, Morgan arrayed his men in depth in three distinct lines each about 150 yards in front of the next. He placed his least experienced troops, militiamen from Georgia and North Carolina, in the front rank. Morgan told them to just fire two volleys, mostly at “the men with the epaulets (officers),” and then they could retire to the rear. From his experience with militias, Morgan knew they would run anyway, so he was just instructing them how to do it effectively.

The second line, placed 150 yards behind the first, was also militiamen, but these were more experienced men from North and South Carolina under the capable leadership of Colonel Andrew Pickens. They too were instructed to fire until pressed by the Brits and then retreat behind the final line. The last line of defenders, located another 150 yards behind the second, was comprised of hardened Continental Army veterans from Delaware and Maryland that Morgan knew could withstand an assault by Tarleton’s men.

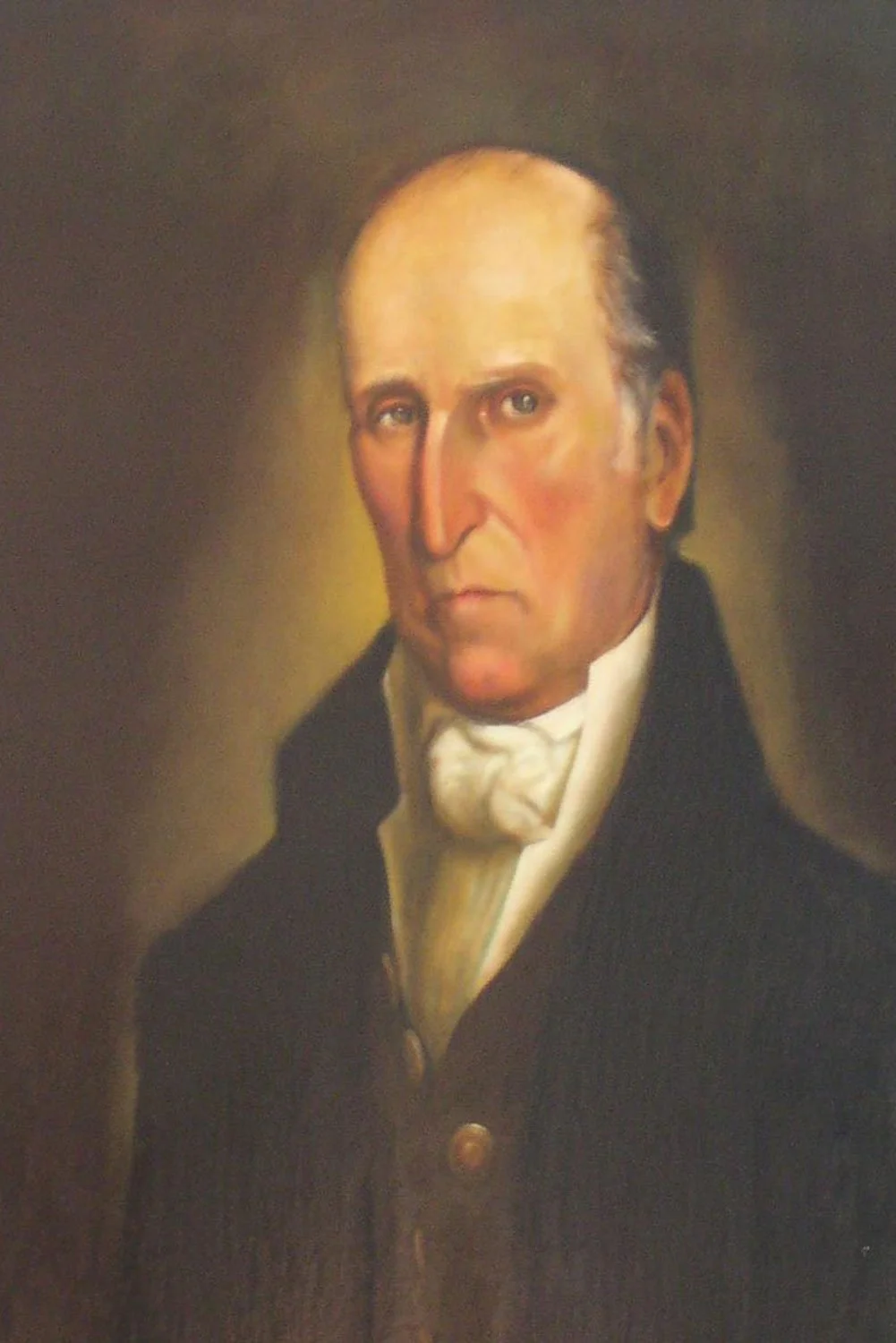

“Gen. Andrew Pickens.” Wikimedia.

Morgan knew that his defense in depth meant that Tarleton’s men would have been attacking over several hundred yards and be exhausted by the time they reached the final American line. Moreover, Tarleton’s men would lose cohesion and momentum as they attacked each successive line.

Tarleton, anxious to bring Morgan to heel, was on the road at 3:00am and arrived at Cowpens with the sun. Despite his men being tired and hungry, Tarleton ordered an immediate attack, just as Morgan had foreseen. The front-line Americans fired their two rounds and headed for the rear, and Tarleton believed the rout was on as it always was with American militia.

Tarleton then sent in all his remaining troops against the second line which also retired to the rear after firing a few volleys. By now, the British soldiers were physically spent but ordered forward with bayonets towards the Continental line at the crest of the hill 150 yards away. To Tarleton’s shock and dismay, these Americans did not run.

As the two main forces fought it out in the center of the field, Morgan sent his cavalry and militiamen, who had reassembled in the rear, against both British flanks. This rare battlefield maneuver, known as a double envelopment, was perfectly executed and, seemingly before the Brits knew what was happening, they were surrounded.

For the next thirty minutes, the fighting was as intense as any during the American Revolution. Using any weapon at hand, bayonets, sabers, bullets, and rifle butts, men mercilessly slashed and jabbed each other. Finally, these Brits, who had never known defeat, had had enough and they began to lay down their arms and ask for mercy.

Tarleton, who was anything but a coward and had been in the thick of the fight, knew further resistance was futile and led 200 horsemen in a fast retreat from the field. What had made him good (his aggressiveness) had made him bad and proved his undoing.

The disparity in casualties for the two sides is shocking. Morgan’s army suffered roughly 150 killed and wounded while Tarleton’s force lost over 1,000 men, representing 25% of Lord Cornwallis’ entire southern field army. This was a blow from which the British would never recover.

John Marshall, the great Supreme Court Chief Justice and former Continental Army officer stated, “seldom has a battle, in which greater numbers were not engaged, been so important in its consequences as that of Cowpens.” Morgan’s own assessment of the battle, given a few days later to his friend William Snickers, was typically succinct and accurate, “We gave Tarleton a devil of a whipping.”

Next week, we will discuss the fight to control North Carolina. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

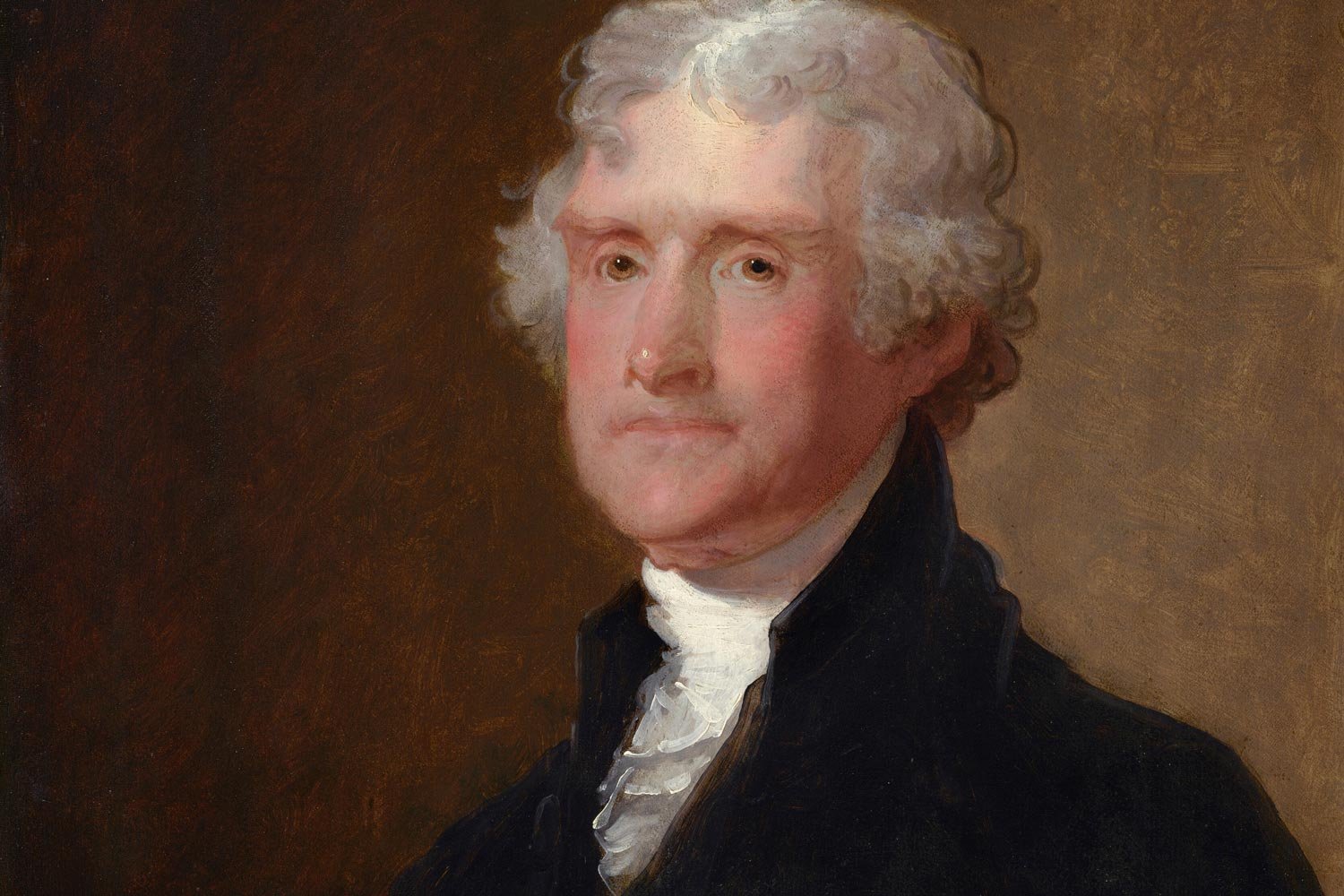

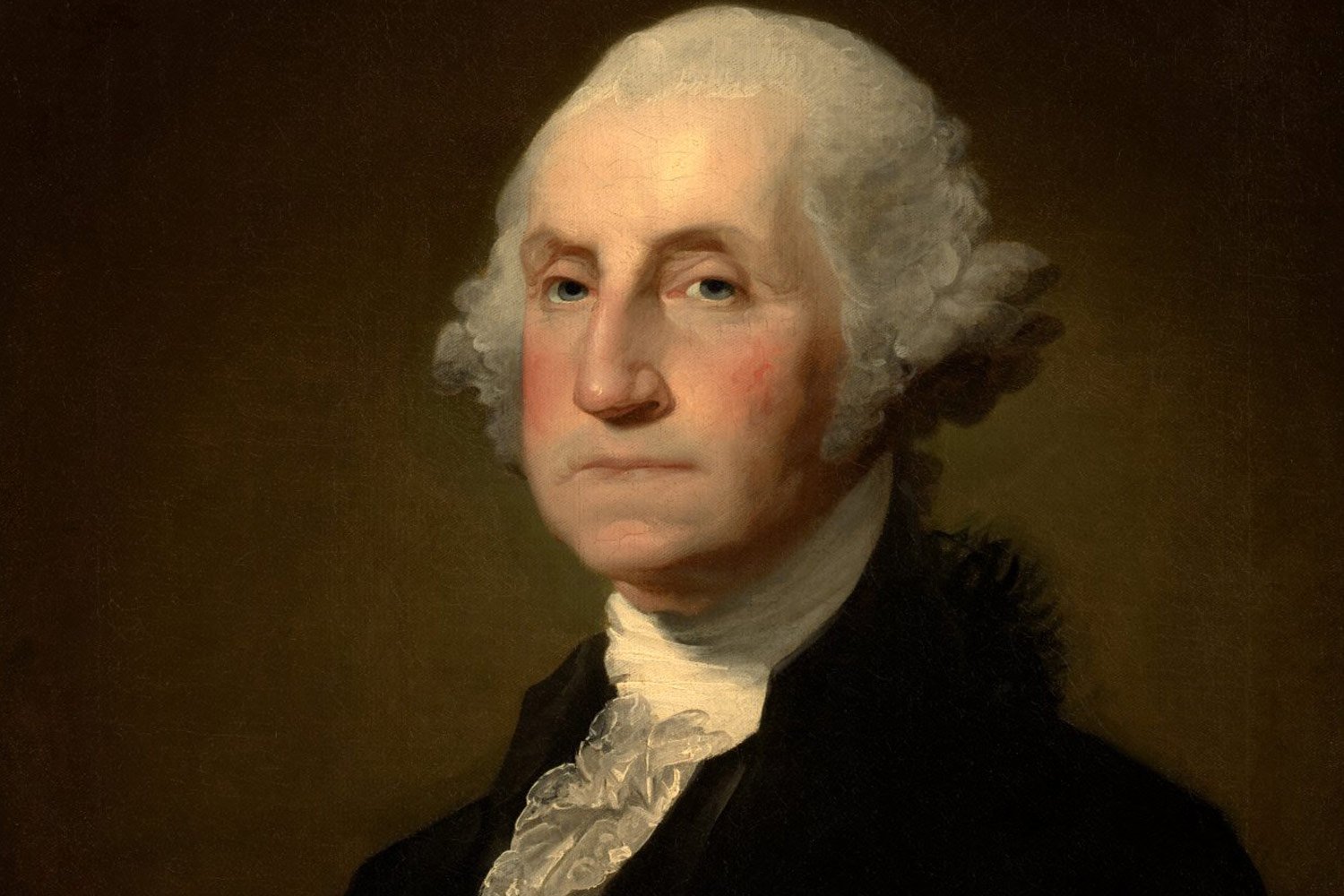

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.