Daniel Morgan Joins Fight for Independence

Daniel Morgan was inspired by America’s desire for independence as early as 1774, when England imposed the Intolerable Acts on the colony of Massachusetts. Morgan felt a natural resentment to this imposition of British authority, tracing back to his unpleasant experiences serving the British army as a wagoner during the French and Indian War.

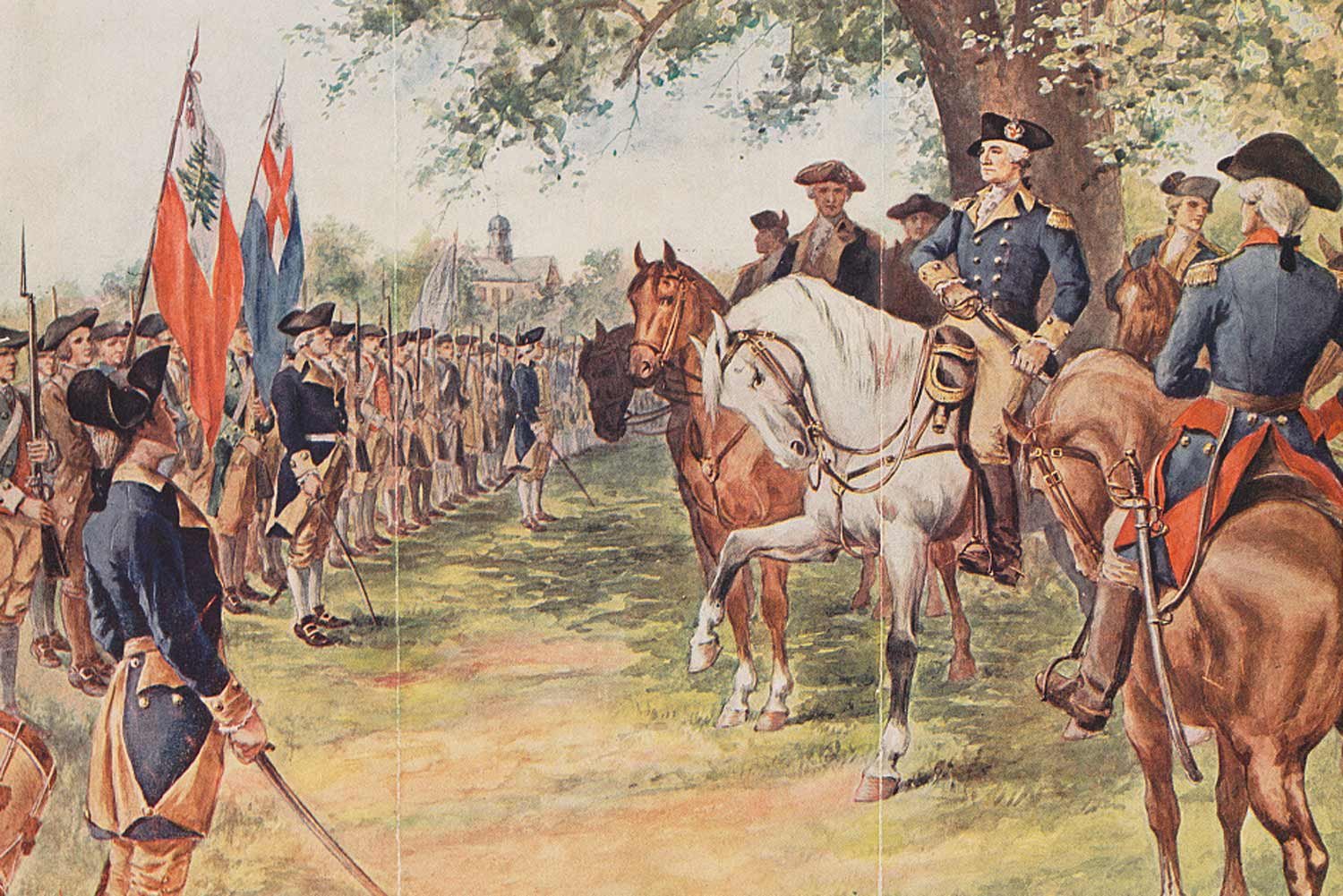

Morgan, who had served with distinction during the recently concluded Lord Dunmore’s War, was offered a captain’s commission by the new Continental Congress on June 22, 1775. Within ten days, Morgan had raised a force of 96 young men much like himself, hardy, fearless, broad-shouldered Virginians. Moreover, they were the best riflemen in the county, and most had been toughened through years of fighting Indians.

They set out immediately for Boston and they arrived at the Continental Army encampment outside the city on August 6. They were conspicuous in their hunting frocks and buckskin trousers, with tomahawks and long knives hanging from their belts. But it was their rifles and proficiency with them that caught the most attention, the weapon being practically unknown in New England.

Their merit quickly recognized, Morgan’s Virginians were selected to accompany Colonel Benedict Arnold on a mission to capture the city of Quebec, in British Canada. They were to proceed through the uncharted wilderness of present-day Maine, a journey estimated to take 20 days and cover 180 miles but ending up twice as long in both miles and days. The ordeal turned out to be one the most impressive marches any American army ever conducted, and Morgan’s leadership was instrumental in the detachment reaching their destination.

They started from Fort Western the last week of September 1775 and within a week the newly built bateaux, fashioned from green wood, began to leak and the provisions to spoil. With each passing day, the troops grew more weary and the food more scarce. By the first days of November, these intrepid men were eating tree bark and shoe leather just to put something in their stomachs. Staring at the bitter end and close to dying of starvation in the wilderness of northern Maine, Colonel Arnold finally secured food from French-Canadians along the St. Lawrence River and saved the day.

Next up for the now thread-bare soldiers was an assault on the walled-city of Quebec, which the Americans launched on December 31. When Arnold, who was commanding one wing of the attack, was wounded early in the fighting, Morgan took over. He immediately charged the gate to the lower town and was the first man over the wall. With a small but hardy band of men, Morgan nearly succeeded in taking the city before being surrounded and captured by British soldiers.

John Trumbull. “The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775.” Yale University Art Gallery.

Morgan spent the next eight months as a prisoner of war, finally getting released from his Canadian captivity in a prisoner exchange. The ship on which he was sailing, the Lord Sandwich, arrived at Elizabethtown Point, New Jersey the evening of September 4, 1776. As the vessel neared the shore, Morgan was overcome with joy and leaped from the ship before it docked. Landing prone on his native land, Morgan clutched the soil and sobbed aloud, “Oh, my country.”

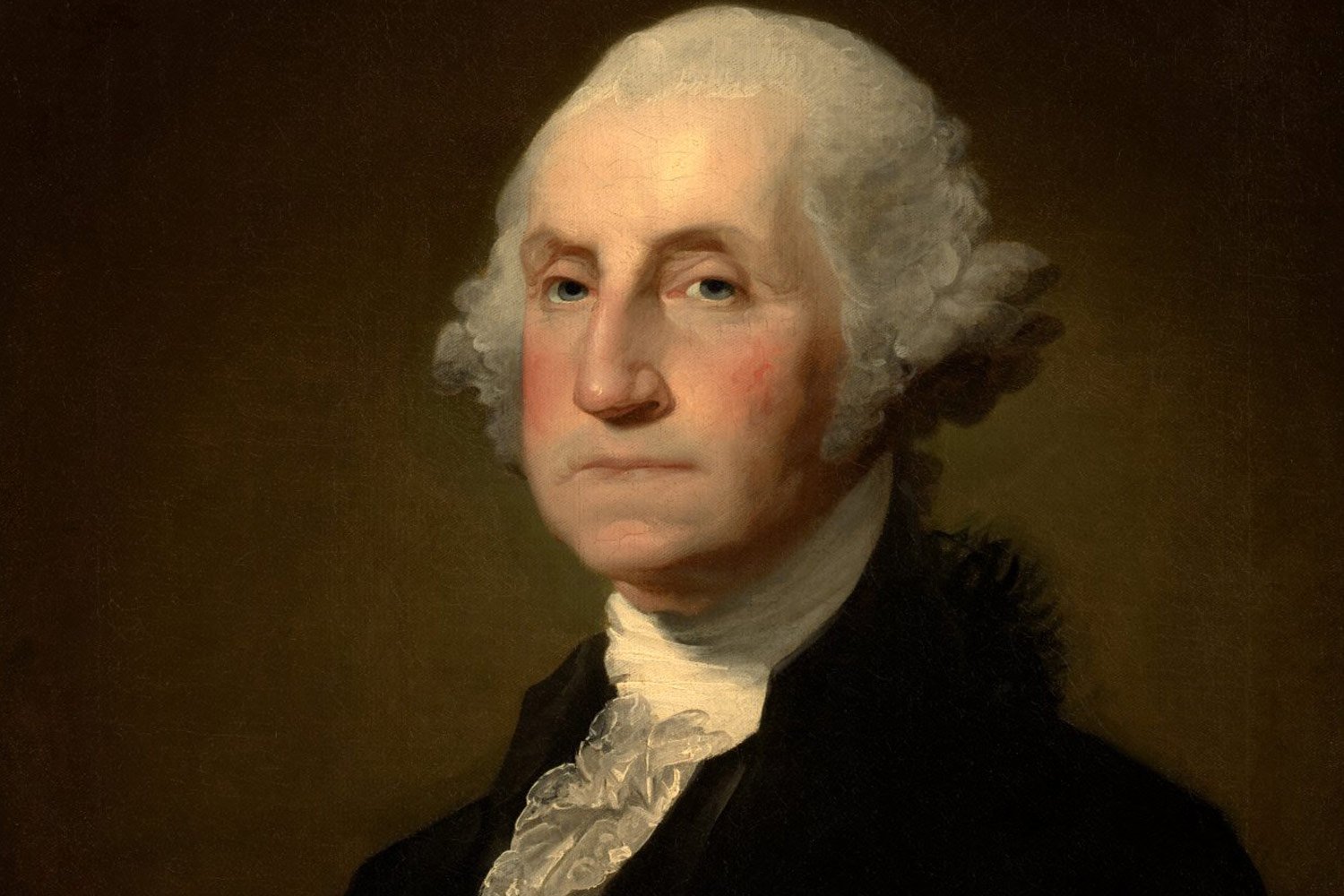

For his gallant behavior during the Canadian expedition, General George Washington, commander-in-chief, recommended Morgan for promotion to the Continental Congress. In November, Congress named Morgan the “Colonel of the Eleventh Regiment of Virginia” and ordered him to raise a contingent of men and report to the main army in New Jersey. He arrived there in April 1777.

In August, following the capture of Fort Ticonderoga by British General John Burgoyne, Morgan and his regiment of riflemen were requested to be sent north by General Benedict Arnold to assist in halting the British advance. The Virginians arrived at northern headquarters on August 23 and were soon put to the test.

On September 19 at Freeman’s Farm and again on October 7 at Bemis Heights, Colonel Morgan and his men performed brilliantly against the Redcoats. The “Old Wagoner,” as Morgan called himself, led his men like a seasoned professional and inflicted severe losses on the Brits, losses they could ill afford. Less than two weeks later, in part to Morgan’s battlefield prowess, General Burgoyne was forced to surrender his entire army.

With the threat to the north over, Morgan rejoined Washington’s command near Philadelphia and spent much of the winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge. Over the next year, Congress promoted several officers to Brigadier General ahead of Morgan, men who had accomplished less but were better politically connected.

Not surprisingly, Morgan grew frustrated by Congress’s apparent lack of appreciation, and, on July 18, 1779, Colonel Daniel Morgan resigned from the army he loved and went home to his family in Frederick County, Virginia. There Morgan would stay for fifteen months, until his country called for him again. He would come out of retirement only briefly, but his impact would be significant.

Next week, we will discuss Daniel Morgan’s masterpiece at Cowpens. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

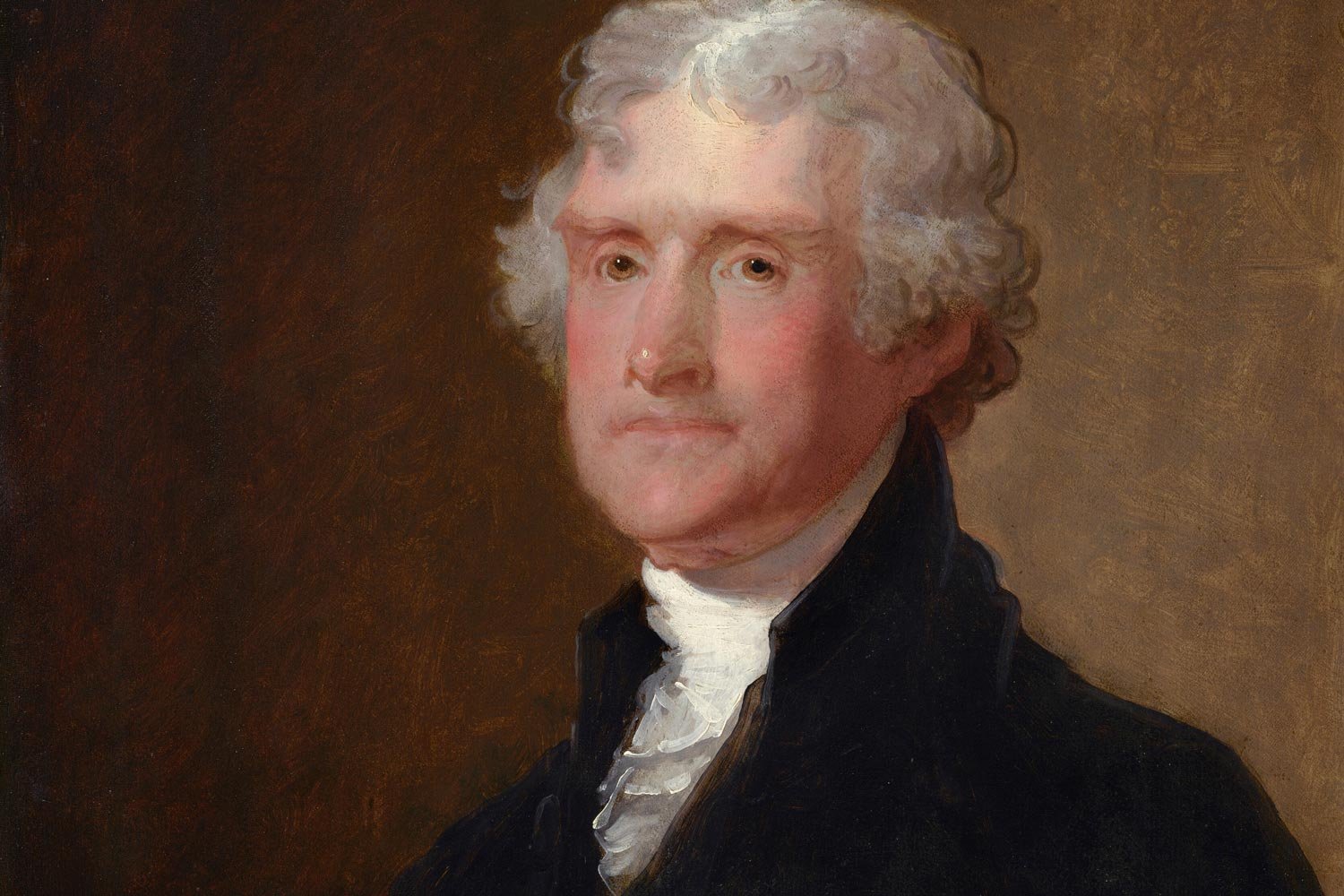

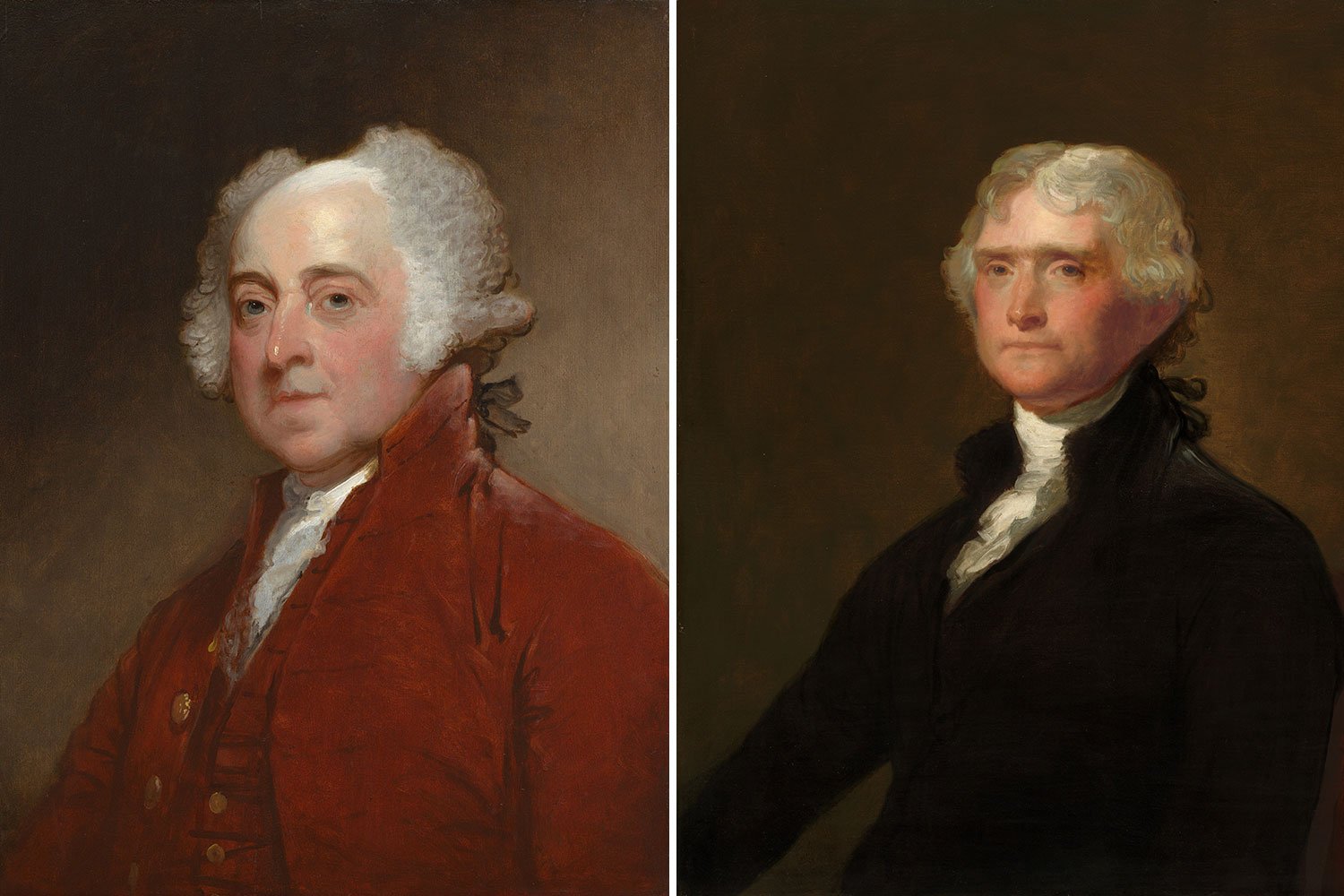

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.