Daniel Morgan Comes of Age

Daniel Morgan, the victor of Cowpens, was one of America’s best battlefield tacticians during the American Revolution. He rose from a hard scrabble childhood to national prominence solely on his merit and ability, overcoming his lack of political connections and wealth. Morgan’s story is a truly inspirational tale.

There is not much known about Morgan’s childhood as he was always non-committal when questioned on it. He was born sometime during the winter of 1736/37 probably in Hunterdon County, NJ but several sources have his birthplace across the Delaware River in Durham, PA.

His parents were James and Eleanor Morgan, who emigrated from Wales in 1720. The senior Morgan was an ironmonger whose foundry, interestingly, would make cannon balls, grape and canister shot for the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Daniel was a big lad and as soon as he was able, his father put him to work clearing land, splitting fence rails, and doing odd jobs on their small farm. Schooling was not a priority in the household and Daniel was just taught the very basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

When Daniel’s mom died, James remarried but the stepmother and Daniel did not see eye-to-eye. At age 17, after a fight with his father, young Daniel decided to head west and make his own mark, eventually settling in western Virginia. He never saw his folks again.

After a year of running a sawmill, Morgan took a job as a wagoner which proved to be a perfect fit for the adventurous, independent minded Morgan. Within two years, he had saved up enough to purchase his own team of horses and a wagon. By now, Morgan was six feet two inches tall, broad-shouldered, and a tower of strength, a man notable for his physical prowess even amongst the very hardy men of frontier Virginia. He had a cheerful nature and a highly intelligent alertness, which helped gloss over his lack of formal education.

In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Morgan volunteered to transport supplies on General Edward Braddock’s ill-fated expedition to Fort Duquesne (present-day Pittsburgh) at the Forks of the Ohio. Braddock’s detachment was badly mauled by the French and their Indian allies, but Morgan survived the battle unscathed.

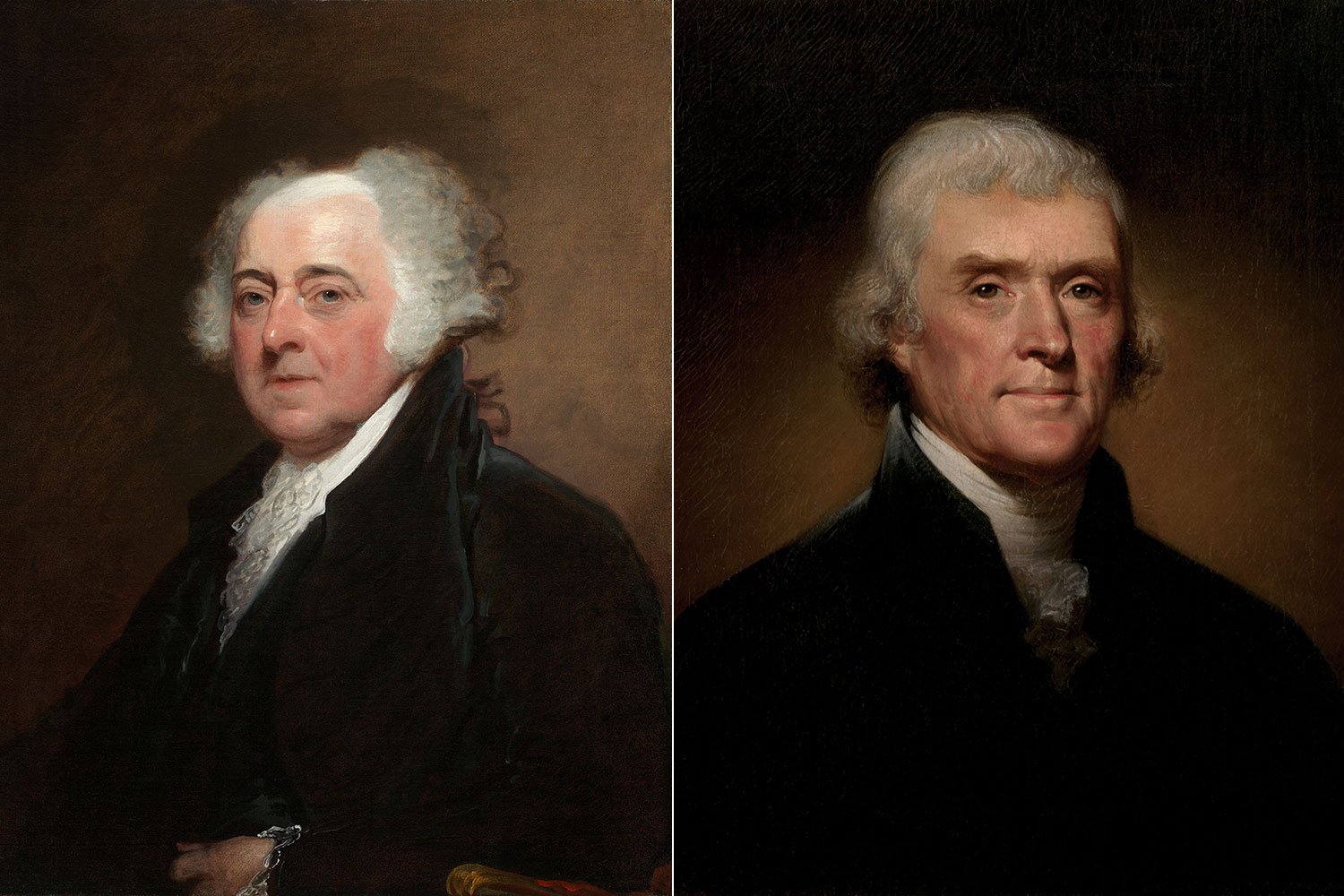

“Washington in the French and Indian War.” Mount Vernon.

The following year, at Fort Chiswell, Morgan was again transporting supplies for the British. One afternoon, Morgan was reveling with some fellow frontiersmen and was a bit too boisterous for a young Lieutenant who told Morgan to quiet down and struck Morgan with the flat of his sword to get his point across. Morgan promptly punched the officer with his huge fist, knocking him unconscious for several minutes.

Striking a British officer was a serious offense and Morgan was ordered to receive 500 lashes on his bare back, typically a death sentence, and it was carried out on the spot. Morgan's back was flayed wide open by a cat-o-nine tails, but Morgan never uttered any protest to the amazement of all. He would later joke that the Brits miscounted one stroke and only applied 499, but he “did not think it worthwhile to tell him of his mistake, and let it go.”

Over the next few years, Morgan fought in several engagements including one in which Morgan and two companions were ambushed by a large party of braves and Morgan’s friends instantly killed. Morgan was shot through the back of his neck, the bullet grazing his neck bone, and exited from the left side of his face, taking out all his teeth on that side but not shattering the jawbone.

Somehow Morgan stayed mounted on his mare and took off for Edward’s Fort, many miles away, with an Indian in hot pursuit and blood pouring from his mouth. Morgan made it to the fort but was on death’s doorstep when he arrived and, even with the best care available, it took six months before Morgan fully recovered. Despite all his future battles and heroic fights, this wound was the only one Morgan ever received.

Following the war, Morgan continued his work as a wagoner and spent his leisure time in true frontier fashion, playing cards, drinking, and fist-fighting. He became known as the toughest man in the area, thrashing all comers. But Morgan was smart enough to recognize the years were slipping by and he was going nowhere fast. That all changed in 1772 when his rowdy spirit was tamed by Miss Abigail Curry, an attractive, feisty girl from nearby Berkeley County, who he married the following year.

For their home, Morgan purchased a two-story wooden house which he aptly named Soldier’s Rest. Abigail had been raised by poor parents and did not have much education but like Daniel she had innate intelligence and good common sense. Largely through hard work and determination, Abigail improved both her own and Daniel’s reading and writing skills. By all accounts, she became a gracious and refined hostess, comfortable in any setting.

The happy couple settled down for what should have been a peaceful domestic life in the beautiful foothills of western Virginia. Then Lexington and Concord happened and all that changed.

Next week, we will discuss Daniel Morgan joining the Patriotic cause. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

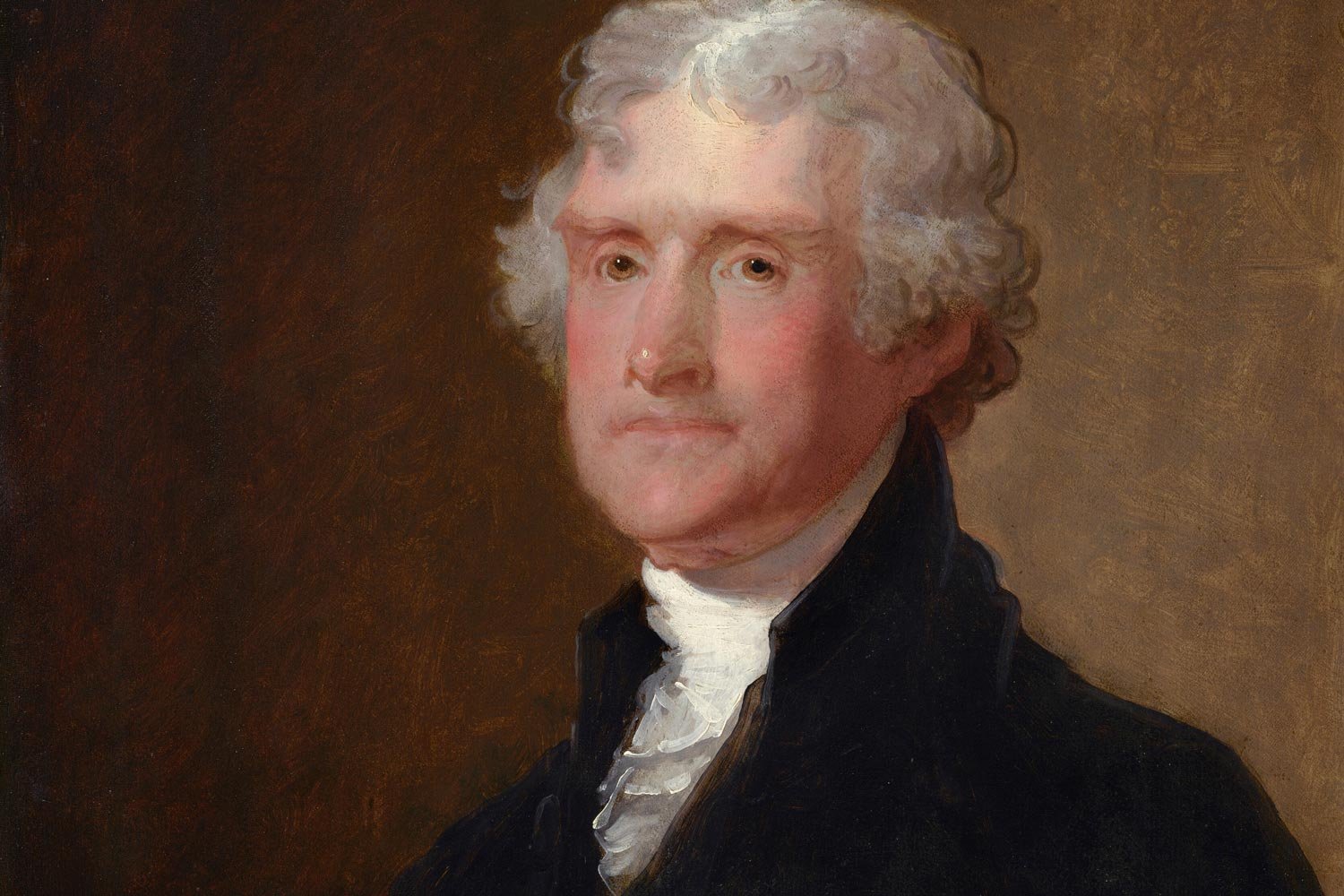

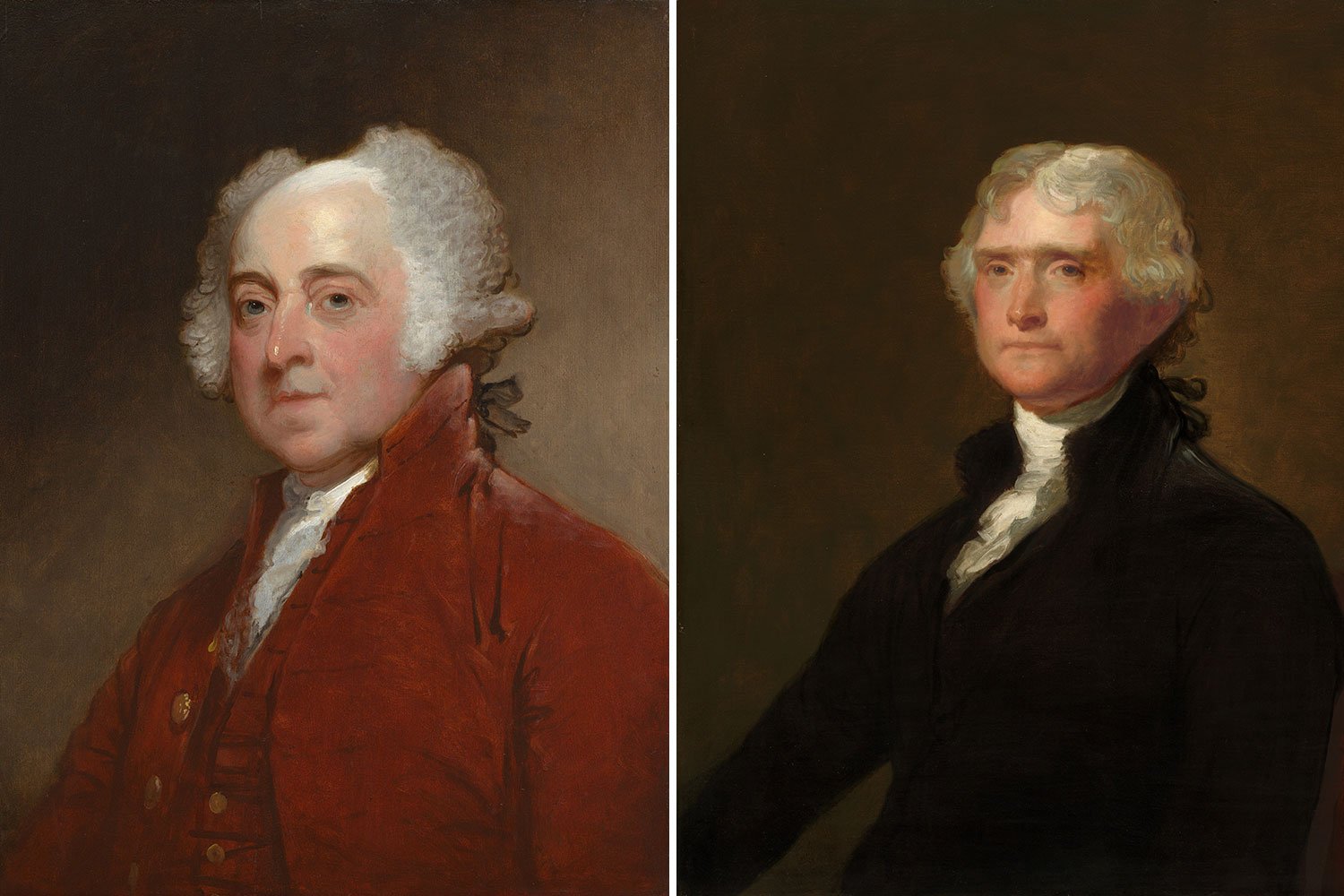

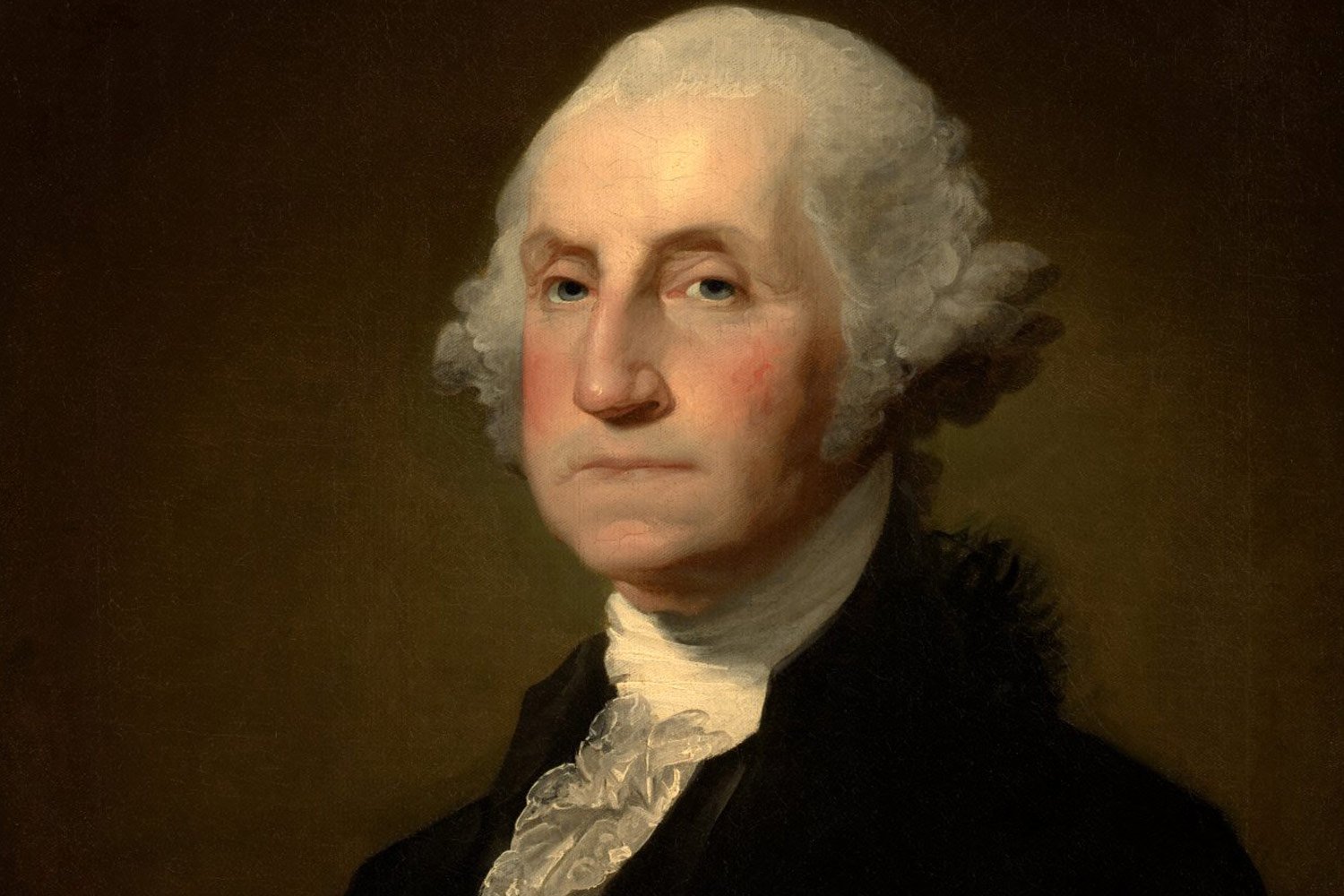

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.