Creating the Constitution, Part One: Enabling the Government to Control the Governed

It is important to understand the challenges faced by the Founders in creating our new federal system. As James Madison wrote, "the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses how the Constitution was created, and why it still matters today.

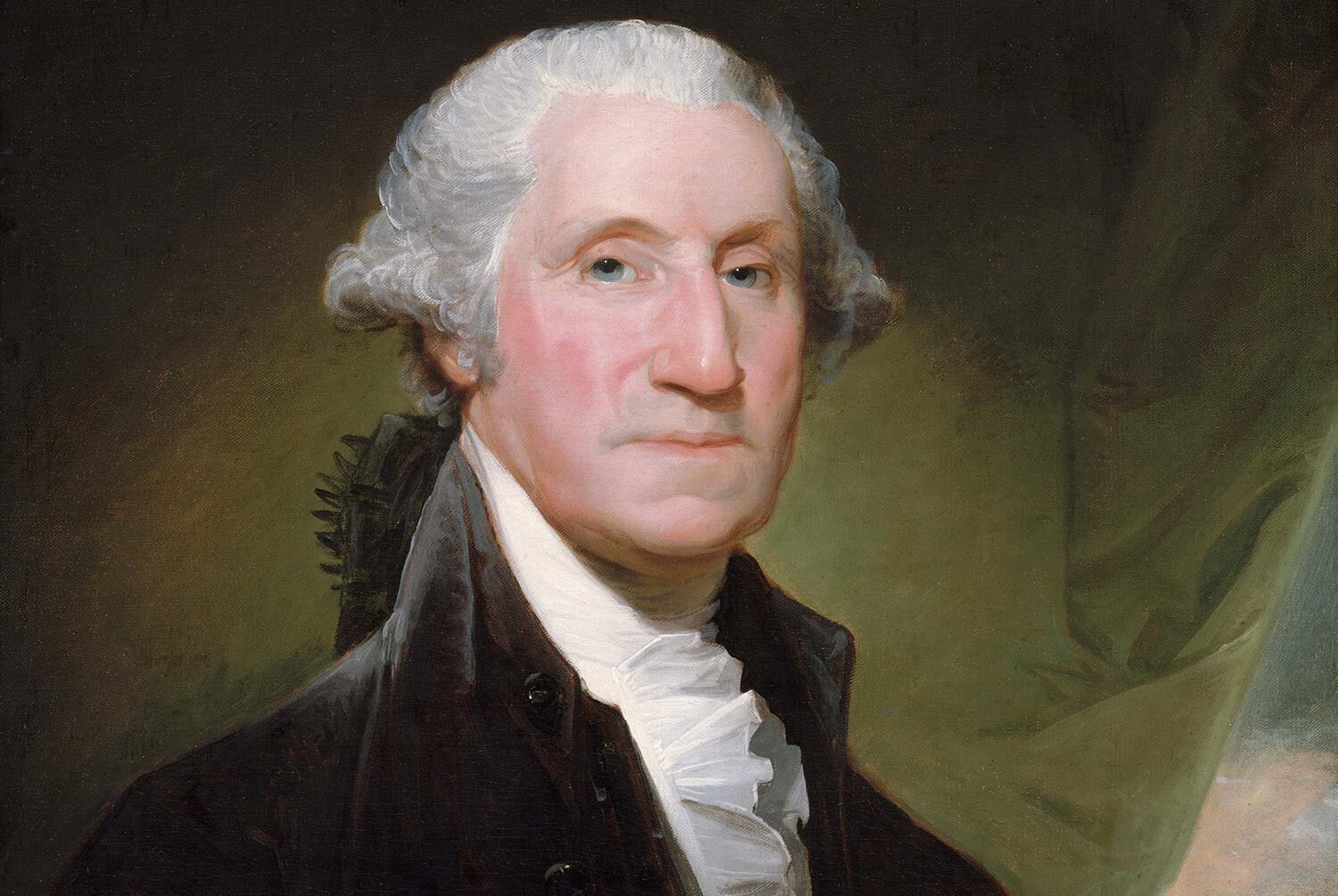

Images courtesy of the National Archives, Library of Congress, Yale University Art Gallery, Library Company of Philadelphia, National Park Service, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, National Gallery of Art.

When delegates met at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, one of the most troublesome questions was what to do about slavery. Not whether it should be abolished, because even the most vehement abolitionist recognized this was neither the time nor the place for that fight. The issues to be decided were how would slaves be counted in the census and whether the states or the central government would control the institution, and what that control would look like.

On May 29, 1787, Edmund Randolph, Governor of Virginia, rose and introduced fifteen resolutions to the Federal Convention. Known to history as the Virginia Resolves or the Virginia Plan, Randolph’s proposal, which was probably drafted by James Madison, was an outline for an entirely new national government. It called for a national executive, a two-house national legislature, and a national judiciary.

In the years immediately following the successful conclusion of its war for independence, the United States struggled to survive under the Articles of Confederation. The nation’s leaders knew something had to be done to fix its many issues for this great experiment in democracy to continue.

In 1785, Franklin, his work done in France, was recalled to America by Congress. He arrived in Philadelphia that September, revered as one of our nation’s greatest patriots. Despite his need for a well-deserved rest, he was kept continually busy receiving dignitaries, wrapping up loose ends from his eight-year diplomatic mission, and with what would prove to be one final opportunity to help his country.

The Tenth Amendment is one of the true foundational amendments of our Constitution. It reserves for the states all rights not granted to the national government by the Constitution, guaranteeing a federalist type of administration.

The Ninth Amendment is one of the two backbone amendments of our Constitution, the Tenth being the other one. It is the amendment that reserves for the people all rights not expressly granted to the government, whether those rights are enumerated or not.

The Eighth Amendment helps make our criminal justice system more just for those accused or convicted of criminal behavior. It is comprised of three rights, each of which plays a part in protecting Americans from a harsh and overly ambitious government.

The Seventh Amendment formally established the rules governing civil trials, as opposed to criminal cases. Its main purpose was to distinguish between the responsibilities of the courts which decided the meaning of laws and those of juries which decided matters of facts as presented in a case.

The Sixth Amendment to our Constitution effectively established the procedures governing criminal courts. At its core, the Amendment ensures that those accused of crimes will get a fair trial and have every opportunity to clear their name.

The Fifth Amendment contains some of the most critical protections in the Constitution for those accused of crimes, safeguards that help keep a tyrannical government at bay. In total, it declares five separate but related rights to all citizens.

The Fourth Amendment is the fundamental basis for every American’s right to privacy. These freedoms are some of the most important granted to us by the Constitution, giving credence to the idea that “a man’s home is his castle”. As basic as these rights appears to us today, it was a relatively new concept prior to our Revolution.

This little-known amendment centered on a very important matter to our Founding Fathers, that of the people being forced against their will to house and feed soldiers and bear the costs. While this matter may seem trivial to us today, it was viewed quite differently in 1776.

The Second Amendment is corollary to one of the most basic natural rights we have, that of self-defense. However, it has recently been the subject of great controversy. Becoming familiar with the history of this doctrine is critical to understanding it.

Beyond the freedoms of religion and speech we previously discussed, there are two other equally important rights granted to the people in the First Amendment that receive less fanfare. These are the rights to peaceably assemble and to petition the government to correct a wrong.

The First Amendment clause forbidding Congress from “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press” essentially means we can say and print what we want, to include making negative comments about the government. Prior to our Bill of Rights, this concept was unheard of.

The First Amendment is arguably the most important one in the Constitution, as it encompasses six essential rights. It covers everything from religious matters to what we can say to how we can pursue grievances against the government.

Soon after the proposed Constitution was circulated to the state legislatures for approval, it came under criticism for several supposed faults, but primarily for its lack of a bill of rights. The group opposing the new Constitution became known as “Anti-Federalists” and were led by George Mason of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts.

The first ten amendments to the Constitution, better known as the Bill of Rights, are what allow us to enjoy many of the day to day blessings of our great country. Freedoms easily taken for granted are enshrined in these revisions to the original document. While the Constitution shaped our government; the Bill of Rights shaped our lives.

When the Founders met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to frame a new form of government, one of the most troublesome questions was what to do about slavery. To understand their dilemma, we must first consider the world view of it at the time and the practical issues associated with its abolition in the United States.

The Constitutional Convention was arguably the most important meeting in our nation’s history. It was there our Founders framed the revolutionary form of government that was to shape America, as well as many other nations around the globe. But it was not without its detractors and disagreements.

One of the major defects in the Articles of Confederation was the lack of an executive, that single individual who was to some degree in charge of the nation. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, this flaw was addressed and the amount of authority to be vested in the office was a major point of contention.

The Electoral College was an idea created by our Founders at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 detailing how our country would elect the President of the United States. Although some consider it a relic from the past, our Founders put a lot of thought into this electoral system and the rationale behind it is sound.

The United States Constitution is arguably the most important legislative document ever written. It has not only shaped our great country, but also influenced many other democracies around the world.

The opening phrase of the preamble, “We the People,” spoke volumes regarding upon whose authority the Constitution rested and suggested the unanimity of country and purpose that this new Constitution would create. It was written by Gouverneur Morris, a delegate from New York, and his eloquent words speak for themselves.