The Siege of Ninety Six

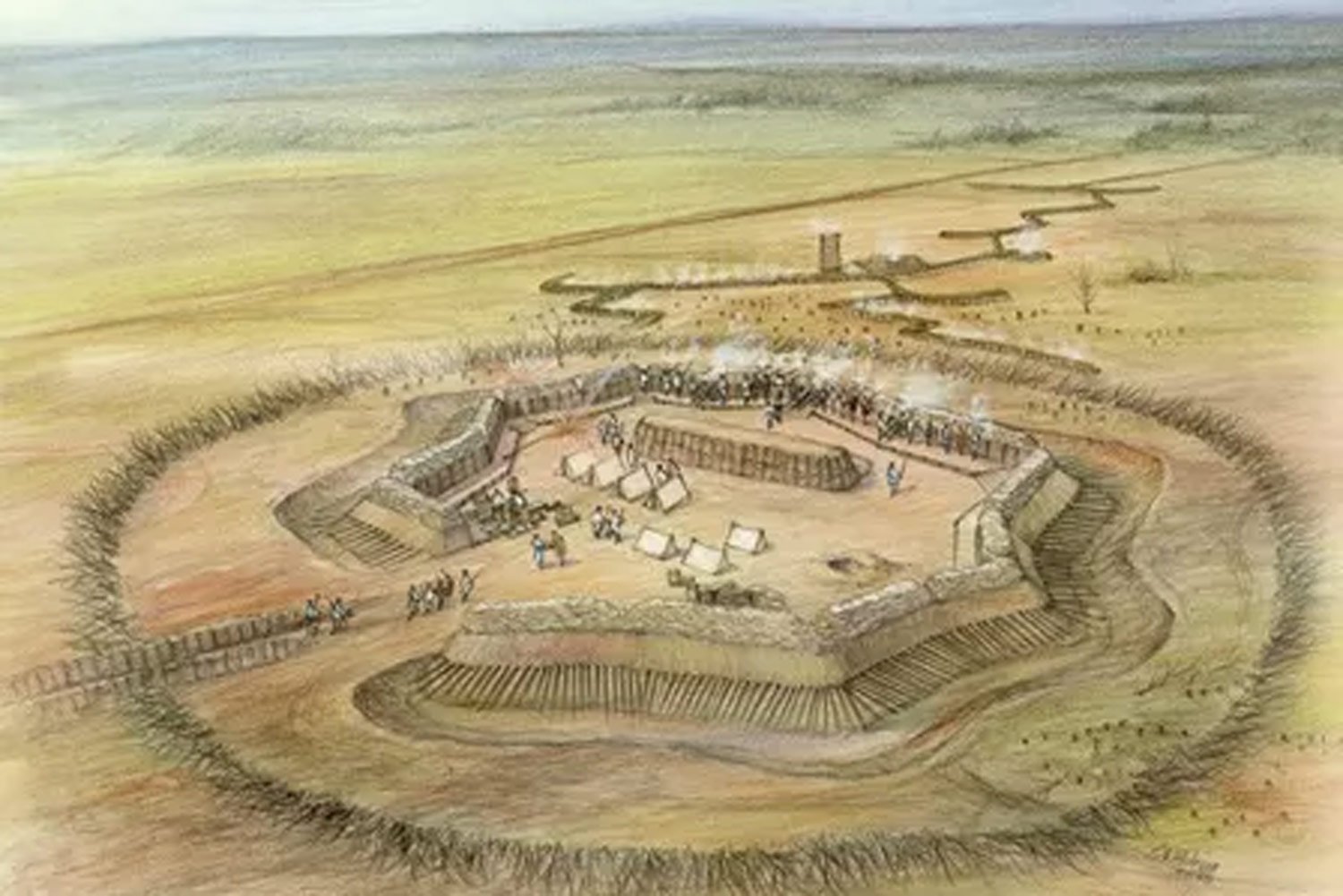

In the spring of 1781, American forces under General Nathanael Greene rolled up the British garrisons in the interior of the Carolinas one by one. The last British holdout was the fortified town of Ninety Six, in the foothills of western South Carolina. On June 12, with the end in sight for the Brits, a rider brought word that a relief column under Lord Francis Rawdon was on the way from Charleston. Greene decided to lift the siege but not before trying one final assault on the night of June 18, an attack that failed terribly.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses the siege of Ninety Six and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Providence College Library, National Park Service, National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian Institution, National Army Museum, The New York Public Library, Library of Congress, Wikipedia.

By the late summer of 1781, the American Revolution in the south was drawing to a close. Hoping to inflict more damage to the British, Major General Nathanael Greene, the commander of the southern Continental Army, planned a strike at the one remaining British army in South Carolina.

In the spring of 1781, American forces under General Nathanael Greene rolled up the British garrisons in the interior of the Carolinas one by one. The last British holdout was the fortified town of Ninety Six, in the foothills of western South Carolina. Greene arrived on the scene with 1,000 men and commenced the siege of Ninety Six on May 22.

When General Nathanael Greene crossed the Dan River and escaped to Virginia on February 14, 1781, Lord Charles Cornwallis’s British army controlled all of North Carolina, and most of South Carolina and Georgia. Within the short span of seven weeks, all that would change.

Following the successful conclusion of the Race to the Dan, General Nathanael Greene and his southern army was safe for the moment from the British troops under Lord Charles Cornwallis just across the river. Due to a lack of supplies in the area, Cornwallis retreated to Hillsboro, about sixty miles southeast, to get refitted. By late February, Greene had received reinforcements, recrossed the Dan, and had the American army back in North Carolina.

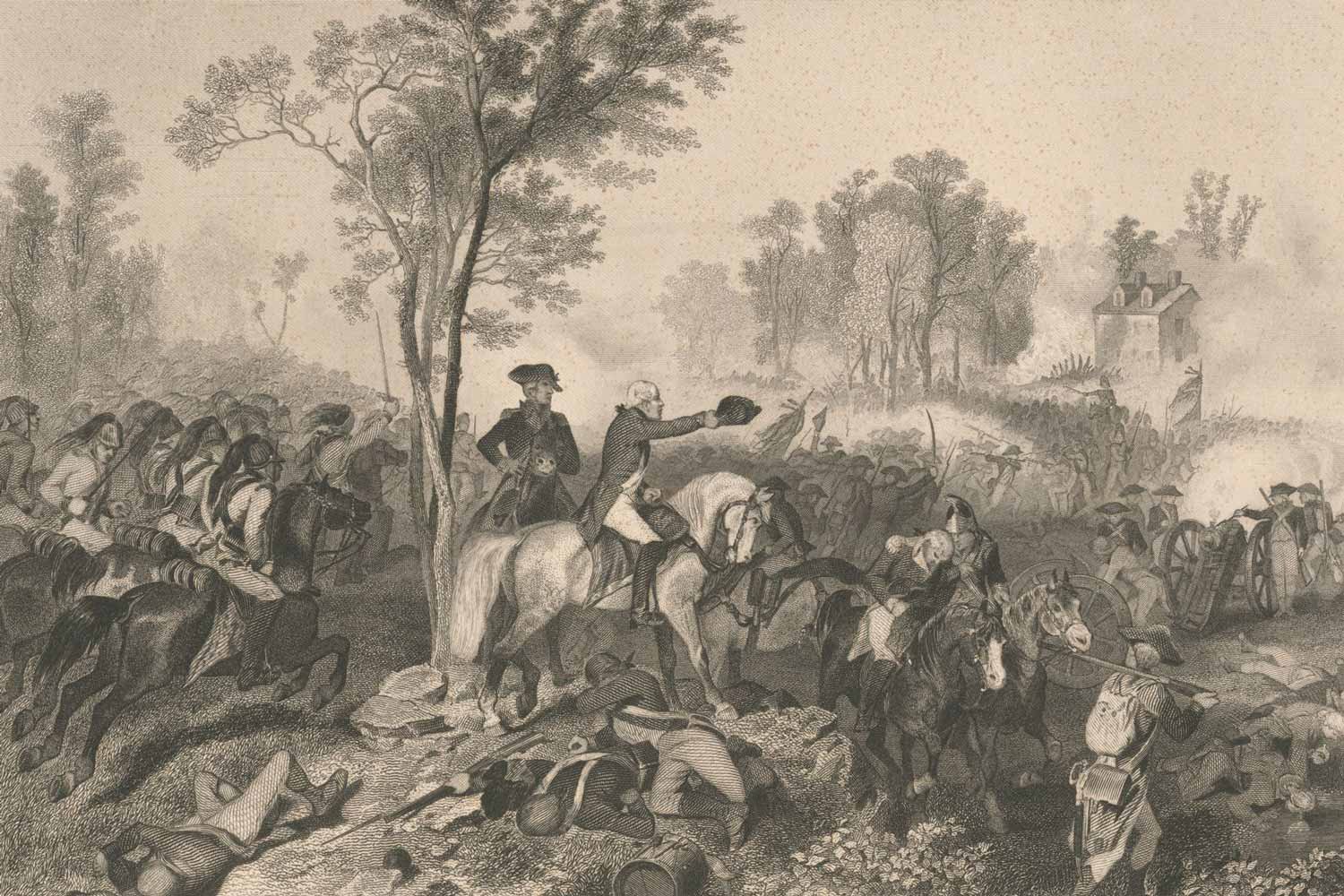

The Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, was a great victory for Daniel Morgan and his army of Continentals and militiamen. They had virtually annihilated Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s famed British Legion, but Morgan’s contingent was in a dangerous position, with a larger British force under Lord Charles Cornwallis only twenty-five miles away. The race was now on to get to a place of safety.

Despite the disastrous defeat at King’s Mountain on October 7, 1780 and several victories by Patriot partisans, Lord Charles Cornwallis and the British army still controlled most of South Carolina and Georgia at end of 1780. The new year would see a reverse of fortunes for the American cause as two gifted commanders, Major General Nathanael Greene and Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, took the helm of the southern Continental Army.

Nathanael Greene was one of the greatest American generals to emerge from the American Revolution. Without any formal military training or any experience, Greene developed into a leader feared and respected by his British counterparts.

This Continental Army General’s family arrived in America in the mid-1600s and soon became prominent and prosperous in their region. As a youth, he had little formal education but managed to find time to study great military leaders of the past. During our War for Independence, he lost most of the battles he fought but managed to hold his thread-bare regiments together.

Nathanael Greene was truly the savior of the south, and significantly responsible for winning the American Revolution. His contemporaries recognized this fact, and awards, accolades, and even land grants were given to Greene.