The Legacy of Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene was truly the savior of the south, and significantly responsible for winning the American Revolution. His contemporaries recognized this fact, and awards, accolades, and even land grants were given to Greene. In October 1785, with his Rhode Island business gone and his finances in a wretched condition, Nathanael, his dear wife Caty and their five surviving children moved to a 2,000-acre plantation called Mulberry Grove. This estate, just west of Savannah, had been confiscated from a Loyalist and was awarded to Greene by the state of Georgia.

Greene worked hard to make Mulberry Grove, abandoned and neglected during the war, a going concern. But fortune did not seem to favor Greene and he never turned the corner in his operations and finances. On June 12, on his way home from Savannah, Greene stopped to inspect a neighbor’s rice fields with him. After spending several hours in the sun, Greene suffered sunstroke. Six days later, on June 19, 1786, this devoted Patriot died, and the nation lost a great man. Greene was only forty-four years old.

Greene was well liked and universally respected for all he had accomplished for the country and his death was lamented by all. More than that, the nation’s leaders knew the United States had lost the services of an eminently talented man and they grieved for the lost opportunities that lay ahead.

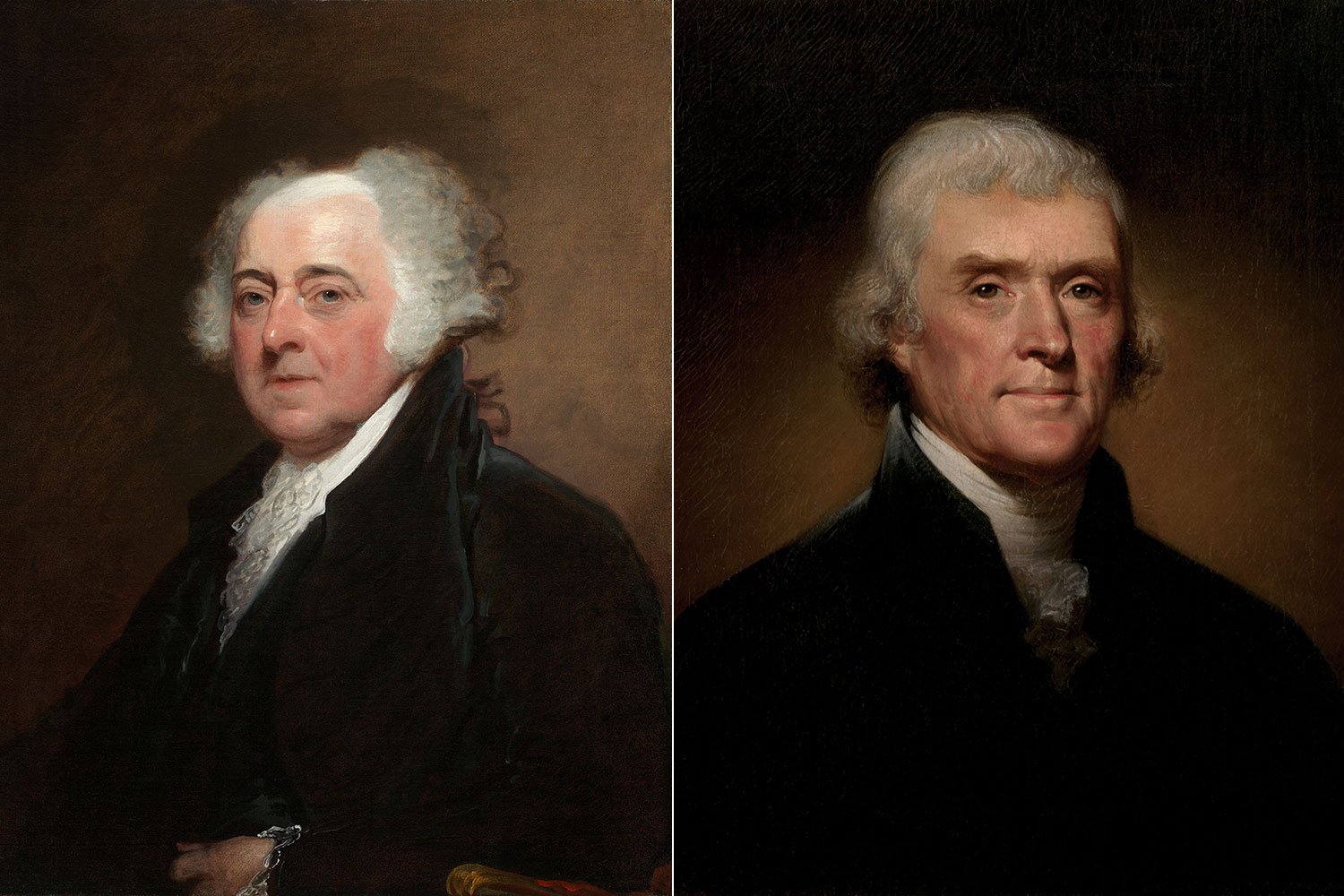

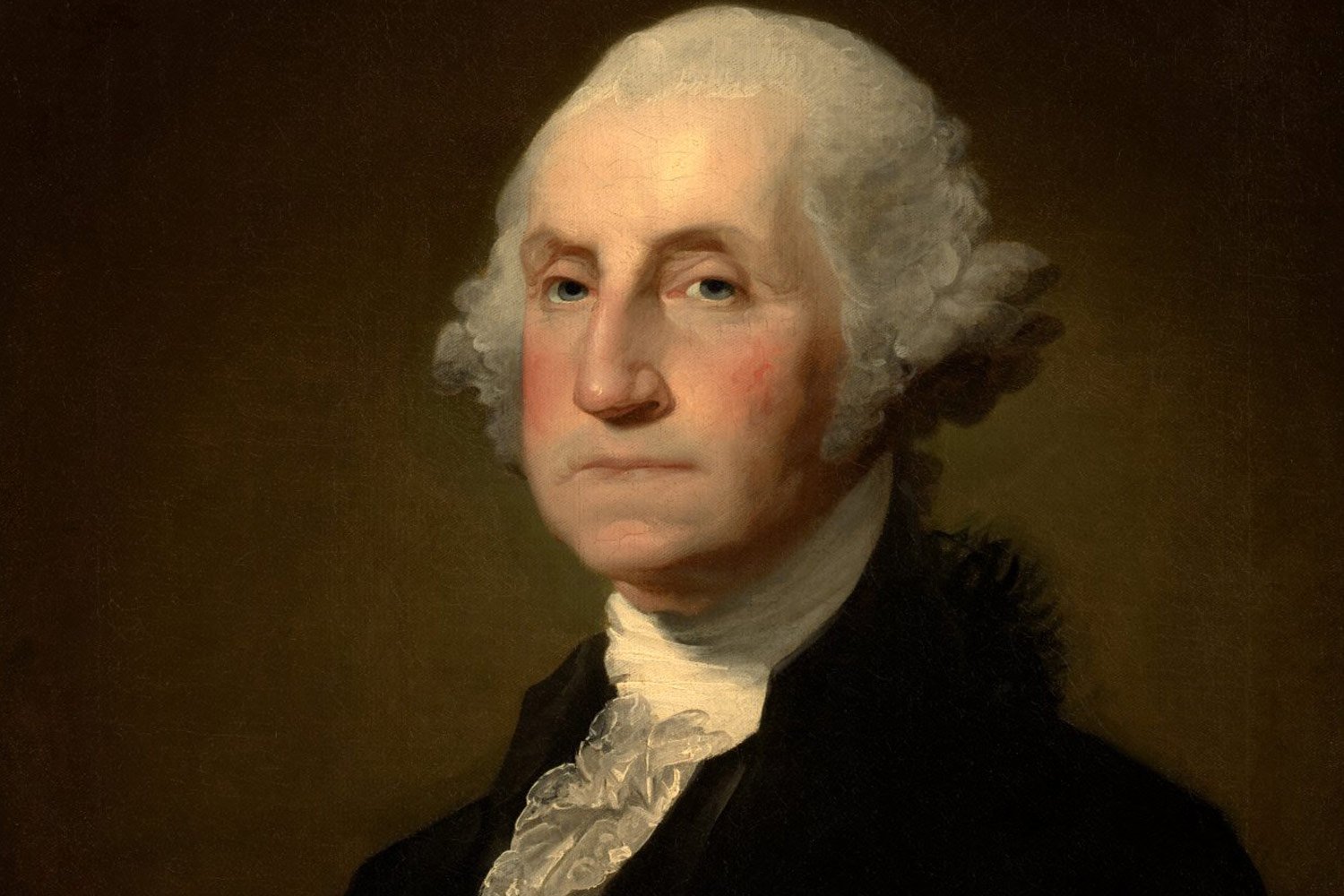

General Washington wrote to Jeremiah Wadsworth, Greene’s business partner, that he mourned “the death of this valuable character, especially at this crisis, when the political machine seems pregnant with the most awful events.” Alexander Hamilton wrote Greene’s passing deprived the country of a “universal and pervading genius which qualified him not less for the Senate than for the field.”

What Greene had accomplished in his two years in command of the southern Continental Army was nothing short of miraculous, especially considering his starting point. The army Greene had inherited was in a shambles after the opening phase of the war in the south saw Americans lose three significant engagements: the capture of Savannah in December 1778, the fall of Charleston in May 1780, and the Continental Army’s crushing defeat at Camden on August 16, 1780.

Between the Charleston and Camden disasters, the American southern army lost 7,400 men, an amount they could not replace. The 2,300 men that remained were poorly supplied and dispirited; many saw little hope for the cause.

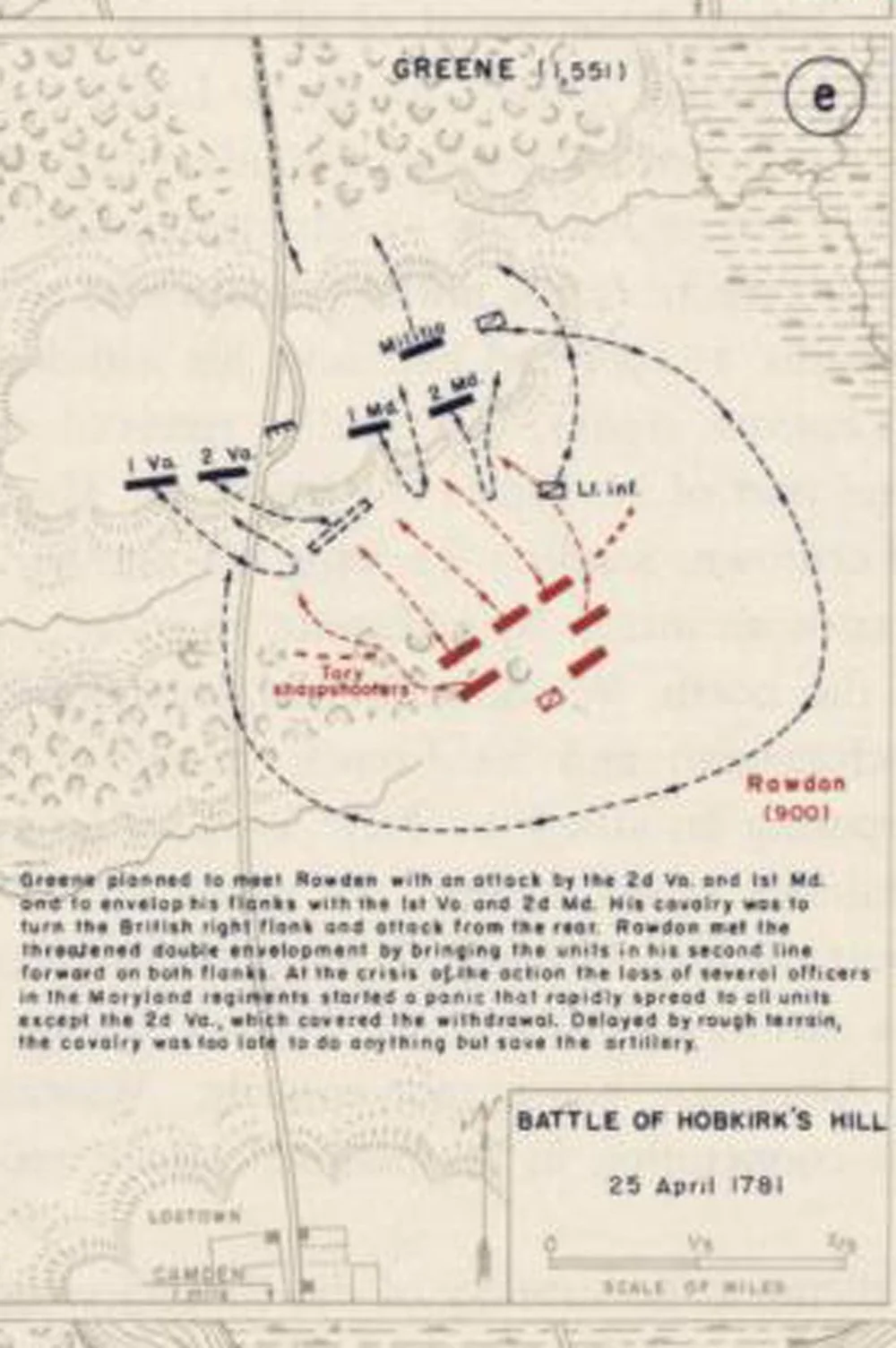

Vincent J Esposito, and Frederick A. Praeger. “The West Point atlas of the Civil War.” Library of Congress.

The enterprising Greene immediately recognized he must modify the American strategy. Rather than engage Lord Charles Cornwallis and his professional British army in large scale battles, Greene used guerrilla tactics to harass and wear down his more powerful adversary. As he wrote to General Washington, “I see little prospect of getting a force to contend with the enemy upon equal grounds and therefore must make the most of a kind of partisan war.”

Following the disaster at Camden, the partisan war which Greene predicted became a bitter fight in the South Carolina backcountry between small bands of angry men roaming the countryside. These engagements, which took place largely from August to December of 1780, were more a series of armed brawls than pitched battles, with little strategy other than kill as many of the enemy as possible. It was here that the Americans held the advantage as their leaders proved much more capable than those of the Loyalists.

After the resounding American victory at Cowpens in January 1781, the war moved from South Carolina to North Carolina. What followed was a war of maneuver with one pitched battle at Guilford Courthouse on March 15. Although technically a British victory, the losses sustained by the Redcoats forced Cornwallis to retire to his supply base at Wilmington. In April, Cornwallis moved his shrinking army into Virginia and closer to his date with destiny at Yorktown.

So why should the life of Nathanael Greene matter to us today? In the final two years of the American Revolution, American deaths in South Carolina totaled almost twenty percent of all the soldiers killed in combat in the war. Additionally, the wounded in South Carolina during this period accounted for almost one third of all casualties in the war. Incredibly, these numbers do not include battlefield casualties of the Loyalists, most of whom were also Americans.

There is little doubt that the British could have maintained a presence in its American colonies for as long as it wished. The reality was that the professional British army and navy and vastly superior supply system gave England what could have been a perpetual advantage over the Continental army and its fleet of privateers. But the tactics employed by Nathanael Greene made maintaining these possessions a costly affair.

Green’s actions forced England to ask itself if the cost of occupying the colonies was worth the price. Given England’s primary goal with its overseas colonies was trade and not acquiring land simply for the sake of having it, they decided it wasn’t. In the end, Great Britain realized it could accomplish their trade objectives by granting independence to the United States and reopening commerce channels. Nathanael Greene played a significant role in shaping England’s decision and for that the United States should be eternally grateful to the memory of this stalwart American.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

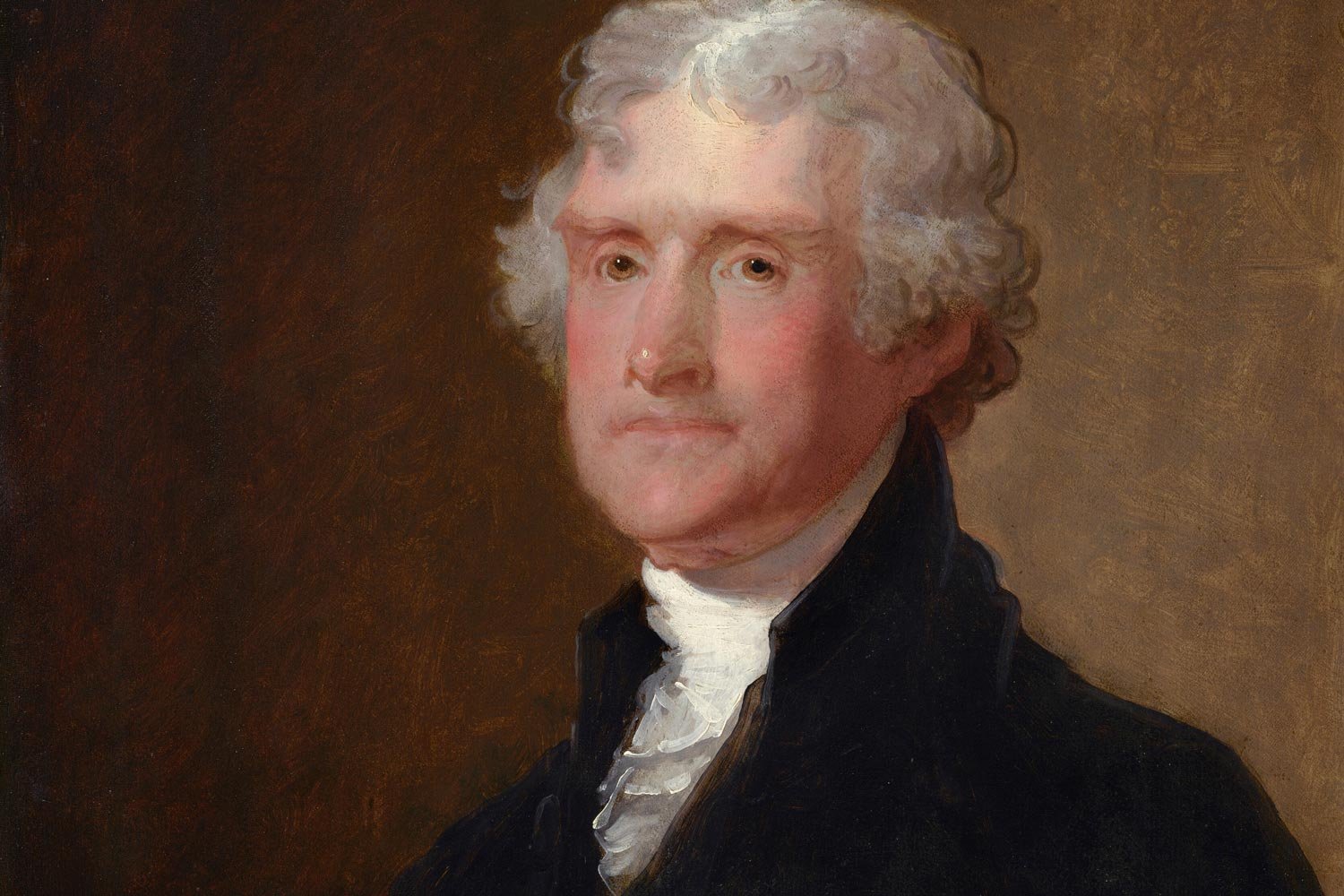

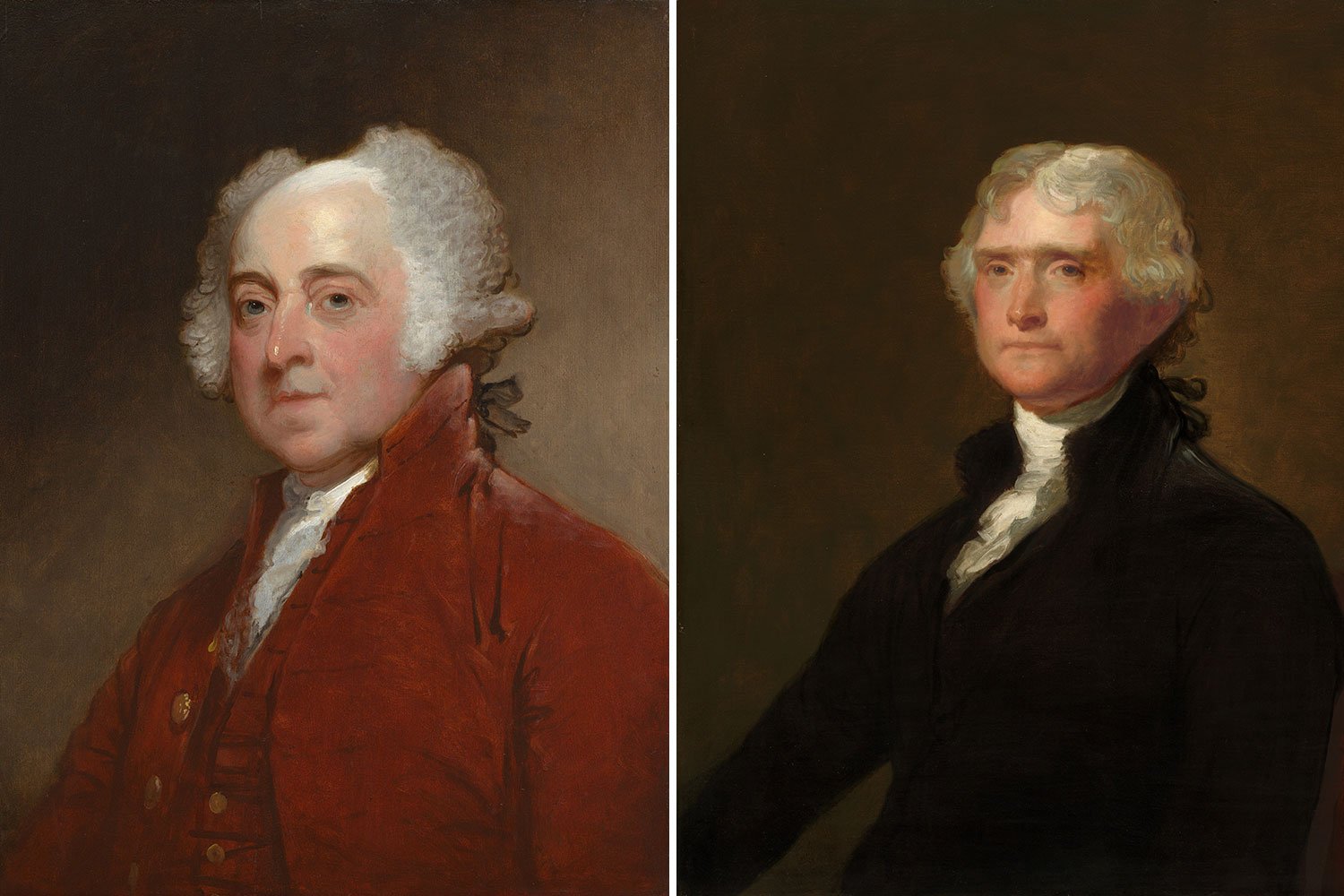

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.