The Continental Army’s Largely Forgotten Invasion of Quebec

The first significant offensive operation of the American Revolution was the largely forgotten invasion of the Province of Quebec by American troops in 1775. It was the opening act of the greater Northern Campaign of 1775-1776 in which the American colonies tried to wrest control of Canada from England. Although it did not end well, there were moments of incredible bravery and perseverance that demonstrated the resolve of our founding generation.

Soon after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, many eyes had turned north towards the British province of Quebec, as Canada was referred to at that time. American colonial leaders reasoned that the inhabitants there might be as disenchanted with Parliament as our thirteen colonies. If we could bring Canada into the American fold, our critical northern flank would be secured.

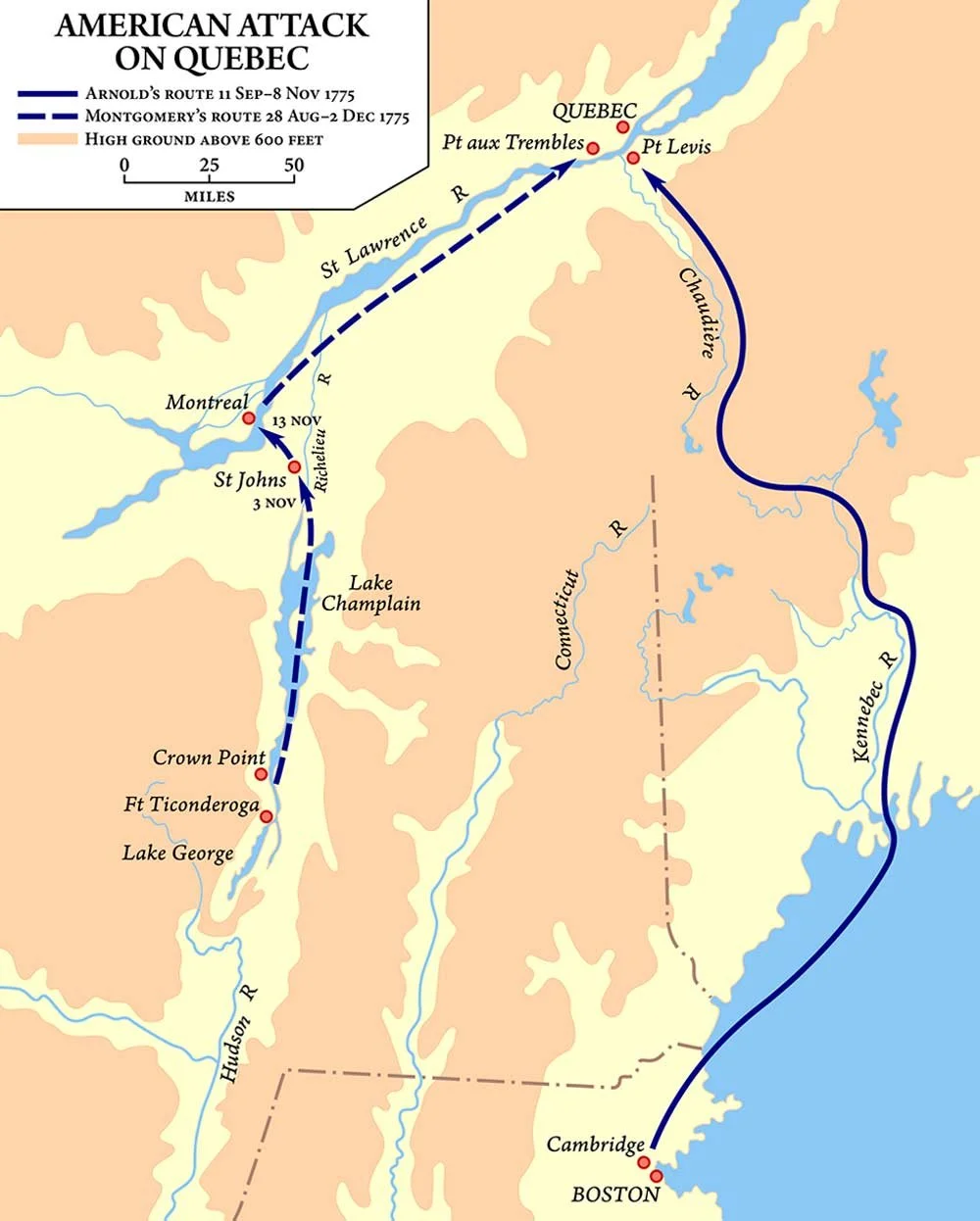

Routes taken by Benedict Arnold and Richard Montgomery expeditions into Quebec as part of the American Invasion of Canada (1775).

As early as the First Continental Congress in 1774, Congressional leaders had invited French-Canadians to join our cause. Although nothing came of this invitation, there was still a widespread belief that if we invaded Canada, the people living there would flock to our banner. This would prove to be a false assumption as the citizenry was largely content with their British administrators due to the sound policies of Sir Guy Carleton, the Governor of Quebec.

Carleton, a former British Army officer, had been installed in this position soon after the British acquired Canada from France at the conclusion of the French and Indian War. He was a thoughtful leader and instituted laws that were considerate of the mostly French Catholic population, and, importantly, he kept both British and American merchants happy.

In May 1775, there were several British posts in the Lake Champlain corridor leading to Canada that were undermanned and considered vulnerable by American military leaders. Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen seized this opportunity and led a force of American militiamen to attack and capture Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point, both on Lake Champlain, and even raided the Canadian settlement of St. John on the Richelieu River, just south of Montreal.

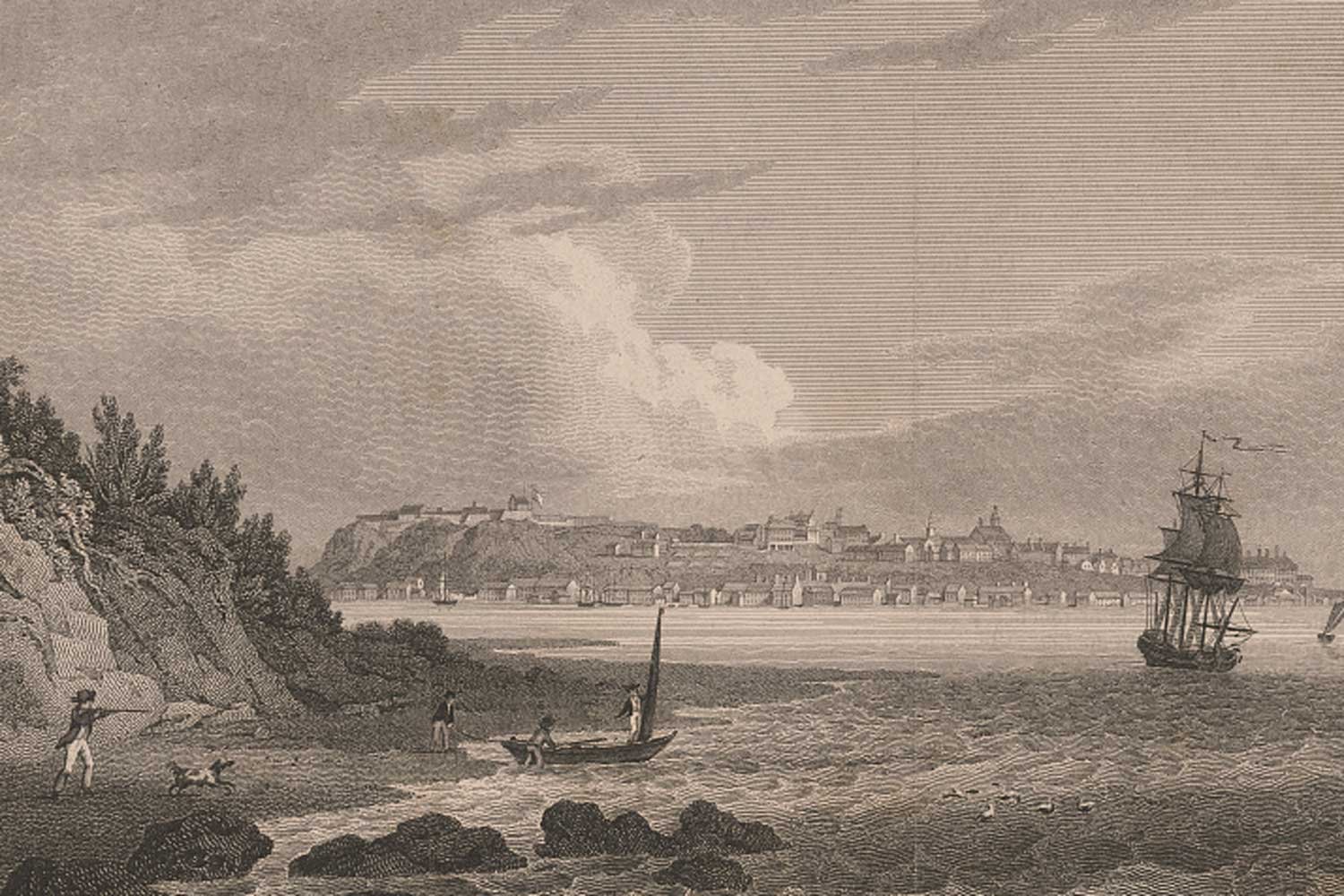

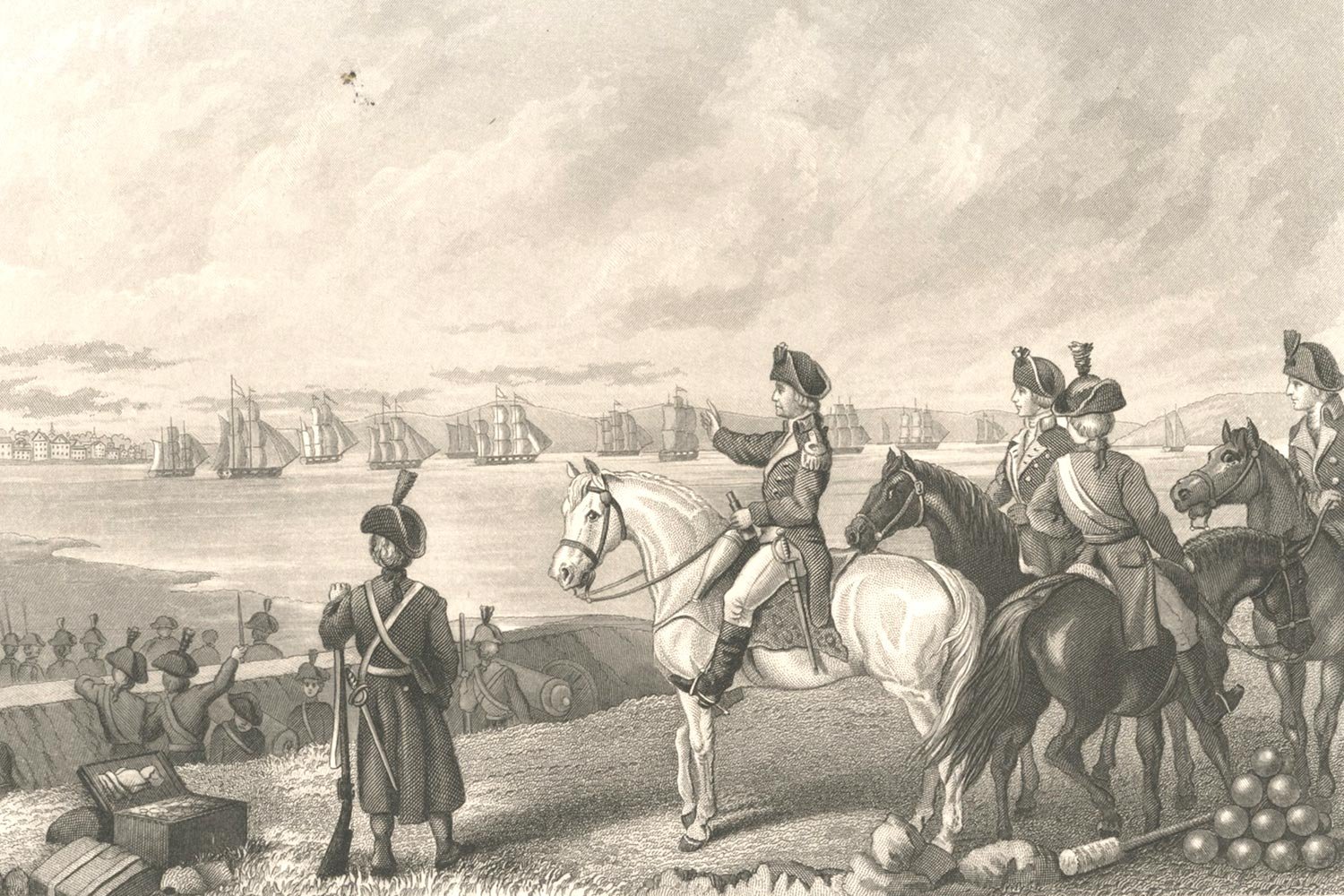

While conducting this raid, Arnold recognized how unprepared the British were to defend Canada from an assault by a determined enemy. This information was quickly relayed to American leaders. On June 27, 1775, Congress ordered General Philip Schuyler, the commander of the Northern Department of the Continental Army, to move north, capture Montreal on the St. Lawrence River, and then continue to Quebec City, the Queen city of Canada, about 150 miles downstream.

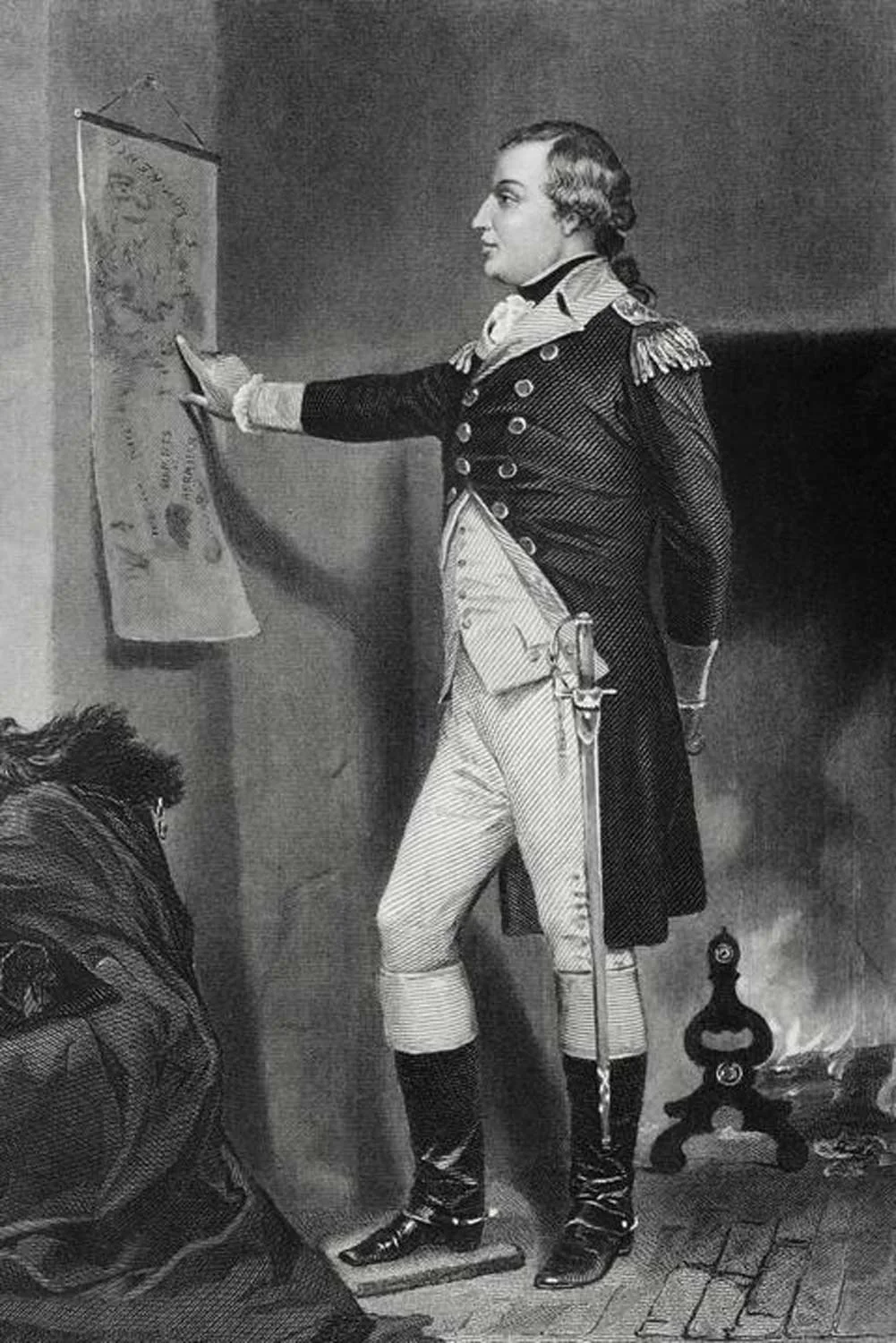

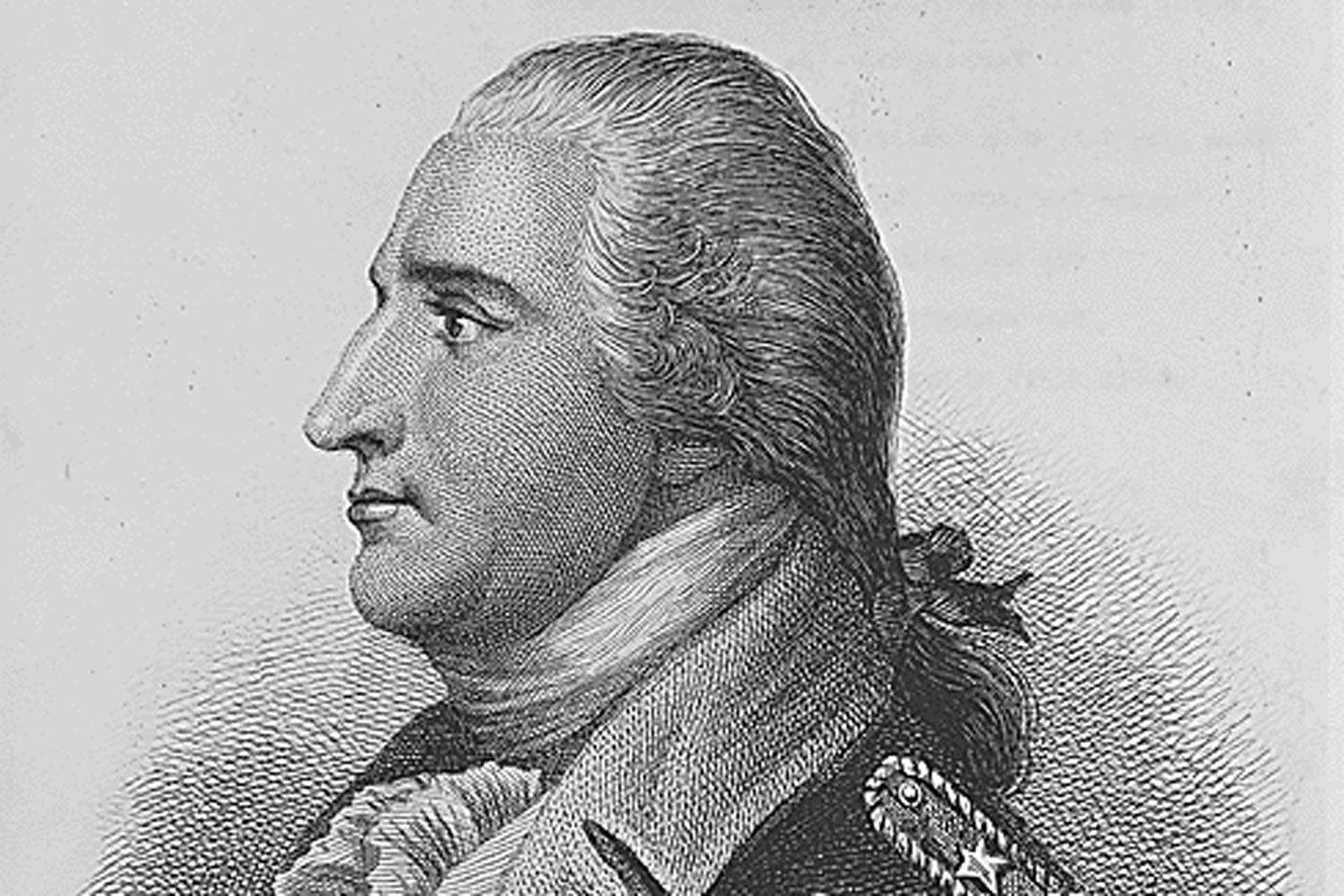

Schuyler was an overly cautious man and moved slowly, tarrying for over two months in New York state. When Schuyler fell ill in late August, he was replaced by General Richard Montgomery, an Irish born former officer in the British Army. Montgomery was an aggressive commander and soon had the troops in motion.

Alonzo Chappel. “General Richard Montgomery.”

They paused their advance on September 4 at Ile Aux Noix, an island in the Richelieu River, just a few miles from Fort St. John, the main defensive position for Montreal. After being reinforced, Montgomery and his 2,000 soldiers laid siege to the fort on September 17. However, the British put up a strong resistance and did not surrender until November 3, forty-five days after the siege began.

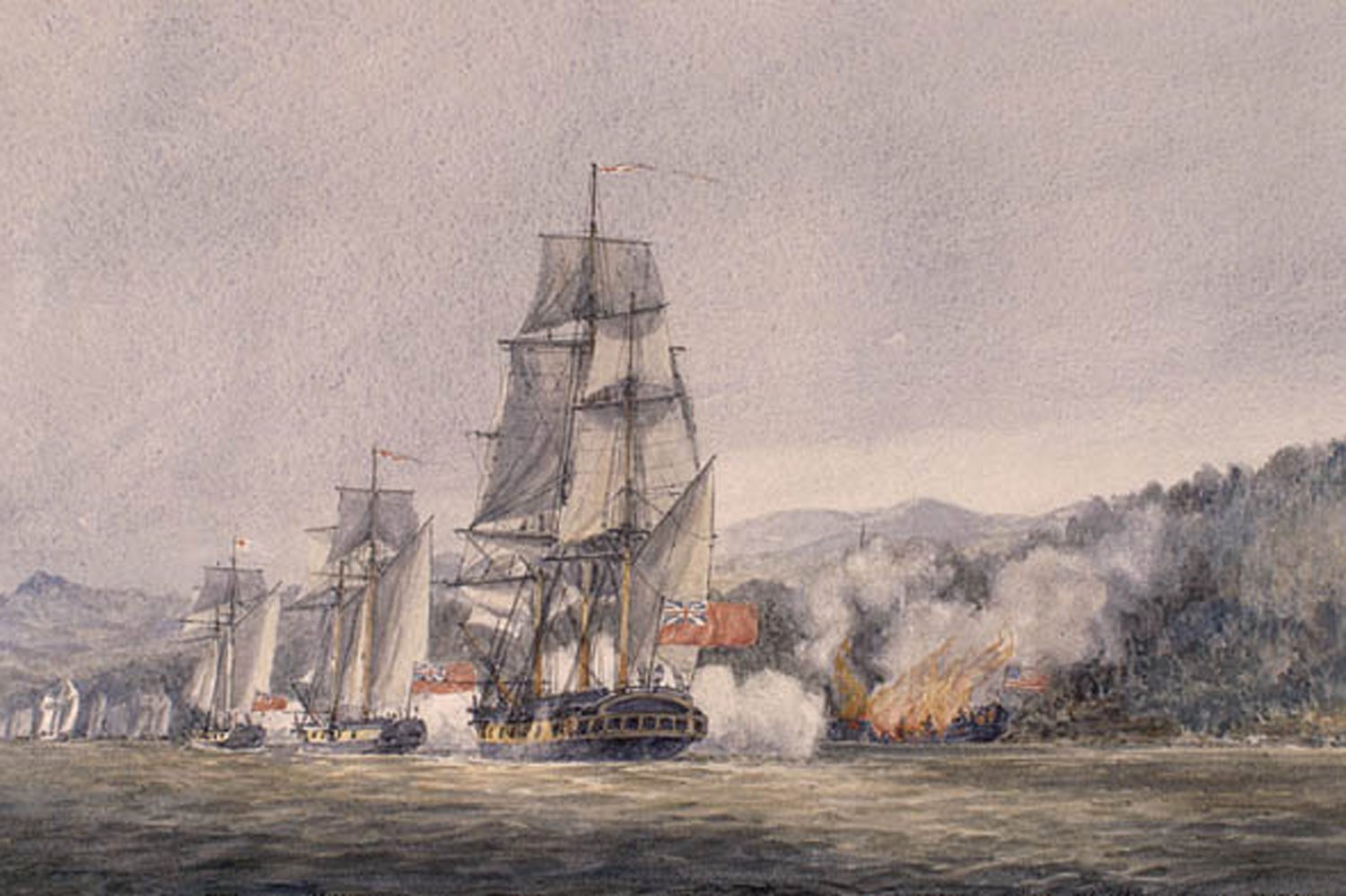

Within a few days, Montgomery had moved his army across the St. Lawrence River and positioned it in front of Montreal. Carleton, the British commander, having most of his militia desert after the fall of Fort St. John, deemed the city indefensible and abandoned it to the Americans on November 13, 1775. Montgomery had successfully captured Montreal, but the delay in reducing Fort St. John would prove fatal to the American effort in capturing Quebec.

Meanwhile, in early August, Benedict Arnold, desperately wanting his own command, set off for General George Washington’s headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts where Washington was busy organizing and training the newly formed Continental Army. There, Arnold hoped to convince the General to create another task force to support Montgomery’s efforts but this one would be led by Arnold.

General Washington, ever aggressive and offensive-minded, liked the concept of a second front for the invasion of Canada. He assigned 1,100 men to Arnold’s expedition, including a contingent of riflemen from the wilderness of Virginia and Pennsylvania under the leadership of Captain Daniel Morgan. The men were excited at the prospect of this hardy adventure after several months of tedious siege duty around Boston.

The energetic Arnold, now a Colonel, immediately began to plan his route of march and to organize the supplies needed for the journey, including the construction of boats to take the force up the Kennebec River. The route would be through an uncharted wilderness and unfamiliar to the entire party. No one fully considered the daunting task in front of them, but reality would soon set in.

Next week, we will discuss the incredible march completed by the troops under Benedict Arnold’s command. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

This article is the first in an eight-part series.

Despite his early successes of capturing Fort Ticonderoga and defeating the American rear guard at both Hubbardton and Fort Anne, Burgoyne now faced the greatest adversary of an army invading a foreign land: a lengthening supply line. As Napoleon remarked, an army marches on its stomach and the British soldiers were no exception.