Arnold’s Army Marches into Trouble

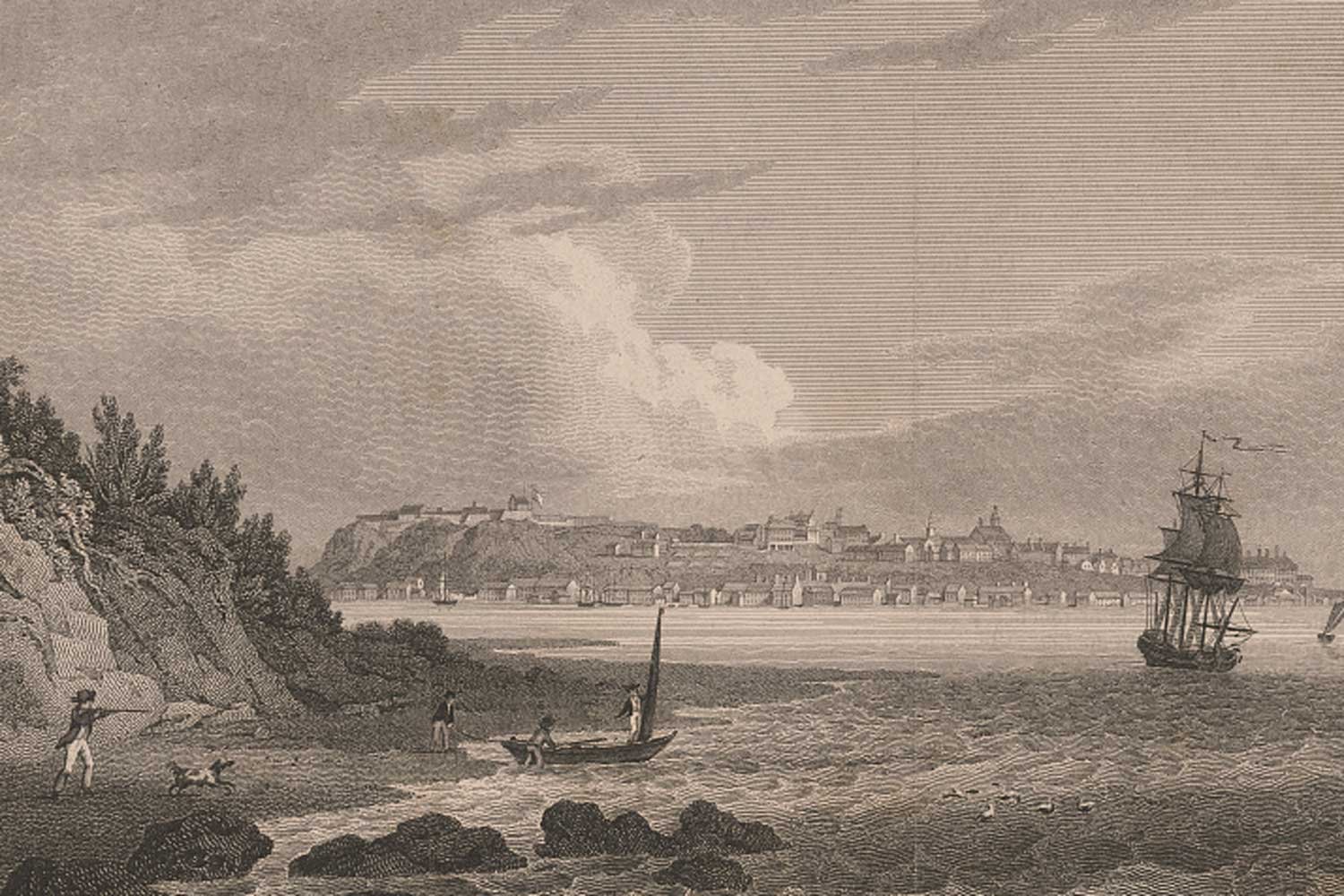

When Colonel Benedict Arnold’s army reached the Great Carrying Place on October 11, 1775, they had been moving north on the Kennebec River for almost three weeks and had advanced eighty-four miles. The American militiamen were on their way to assault Quebec City, the crown jewel of British Canada. The time originally estimated for the entire journey to Quebec was about twenty days, and the anticipated distance was 180 miles. Neither Arnold nor the men were aware they had another 300 miles to go.

The portage around the Great Carrying Place was thirteen miles of rough, roadless woods with an elevation rise of over 1,000 feet. The lead elements under Captain Daniel Morgan began chopping a crude path over which the men could carry the 400-pound boats and remaining supplies. It was a daunting task, but not the end of their hardships.

“Carrying the bateaux at Skowhegan Falls.” Library of Congress.

Once the troops reached level ground, they immediately encountered mossy bogs in which they sank up to their knees with every arduous step. The men floundered as their feet were sucked into the mud and many fingers were broken as the heavy boats they carried slipped from their grasp. After the bogs, they traversed a chain of three lakes before the leading regiment finally arrived at the Dead River on October 13.

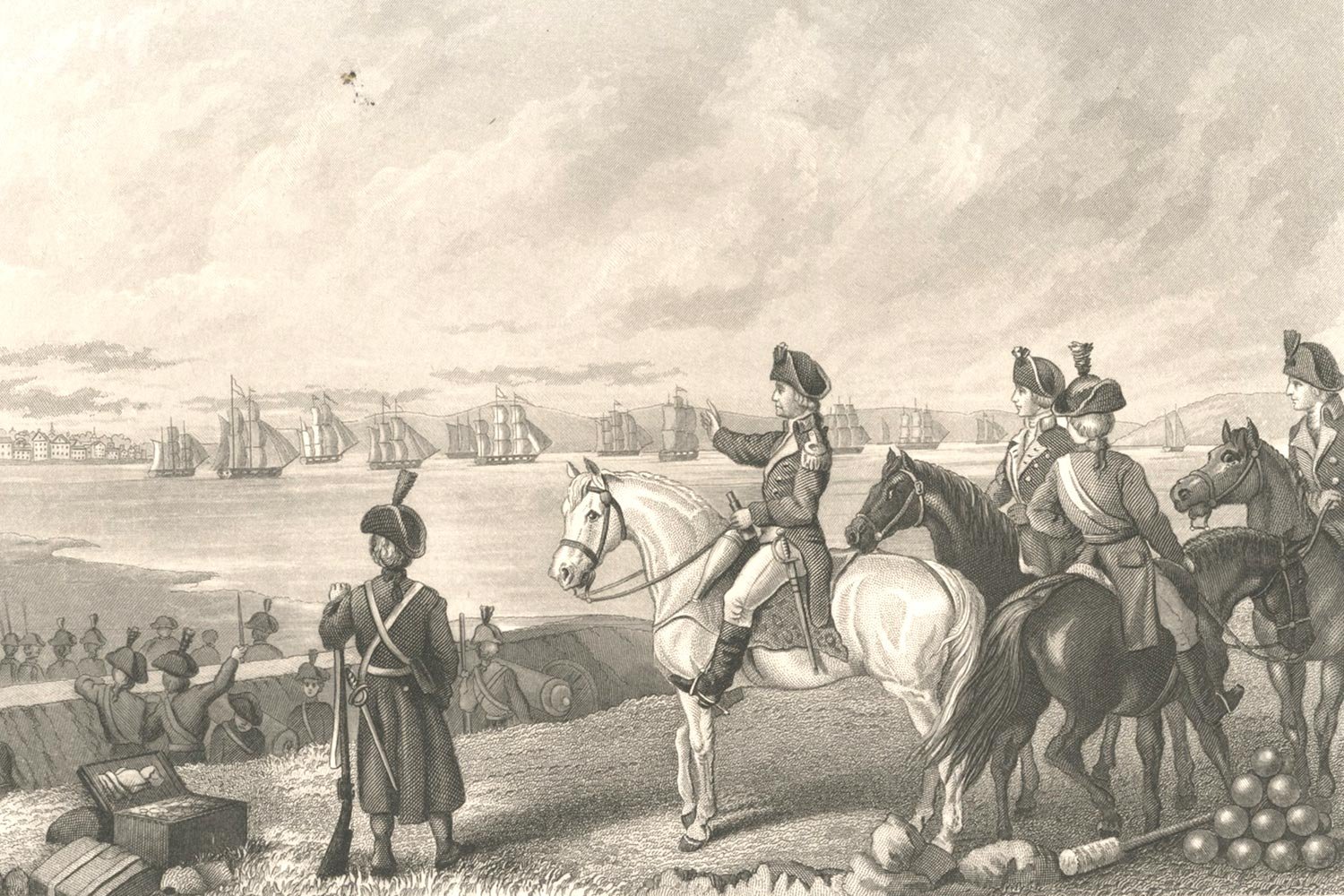

During this trying period, Arnold was a whirlwind of activity and seemed to be everywhere at once. Rather than use the cumbersome bateaux, he cruised the Kennebec in a sleek canoe which enabled him to traverse the long line of boats and encourage his men to keep heart. He also sent parties ahead to scout the wilderness and dashed off a flurry of letters to Generals George Washington and Robert Montgomery, informing them of his progress, and to French-Canadians known to be supportive of our cause.

The Dead River, a tributary of Kennebec, derived its name from the slow pace of the water. After resting for three days, Arnold’s men moved out and made decent progress; it seemed the worst was behind them. However, on October 19, a freak, off-course Caribbean hurricane visited the area and the heavens opened up. For four days, the soldiers were exposed to increasingly heavy rains and strong winds.

During the nighttime hours on October 23, the Dead River rose eight feet in about nine hours, and sleeping men were awakened by water flooding their tents. As they scrambled about, boats and supplies were being swept downstream. The men grabbed water-soaked blankets, boxes of food, and any other personal belongings they could secure and headed to higher ground.

Colonel Arnold held a council of war with the officers of the lead division to discuss the army’s next steps. Despite the terrible hardships and food supplies being dangerously low, Arnold persuaded the men who were able to continue forward reminding them of the importance of their mission.

They sent back in some their remaining boats those that were sick or simply too weak to proceed. Arnold went ahead a team of fifty men to find food at the French villages along the Chaudière River and send it back to the advancing army.

“Major-General Henry Dearborn.” Art Institute Chicago.

However, a few miles downstream from Arnold, the rear division under Colonel Roger Enos was holding their own council of war. Without the fortitude of Benedict Arnold to brace up the men, Enos and the others opted to turn back without orders. This unit, which comprised about 450 men, also happened to have most of the remaining provisions for the army. After sending forward a paltry two barrels of flour, the Connecticut militiamen and the rest of the provisions headed for home.

When the other men learned of their abandonment by the “returners,” they did not send them any well-wishes. Captain Henry Dearborn, who was leading a company of hardy New Hampshire men, wrote in his diary, “Our men made a general prayer, that Colonel Enos and all his men, might die by the way, or meet with some disaster, equal to the cowardly dastardly, and unfriendly spirit they discovered in returning back without orders.”

The next challenge for the expedition was to climb the Height of Land, the rugged ridgeline that marked the border between Canada and the United States and divided the waters of the St. Lawrence from the Kennebec. The ascent was about 35 degrees and a difficult climb under normal circumstances.

For the starving men hiking over snow covered ground, many with rags for shoes, and exhausted after a month of grueling work, it was almost too much. But they persevered and made it over this enormous ridge…and promptly got lost. They would need to summon up even more courage before their trials and tribulations were over.

Next week, we will discuss American forces reaching Quebec. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

This article is the third in an eight-part series.

Despite his early successes of capturing Fort Ticonderoga and defeating the American rear guard at both Hubbardton and Fort Anne, Burgoyne now faced the greatest adversary of an army invading a foreign land: a lengthening supply line. As Napoleon remarked, an army marches on its stomach and the British soldiers were no exception.