Americans Retreat After Failed Assault on Quebec

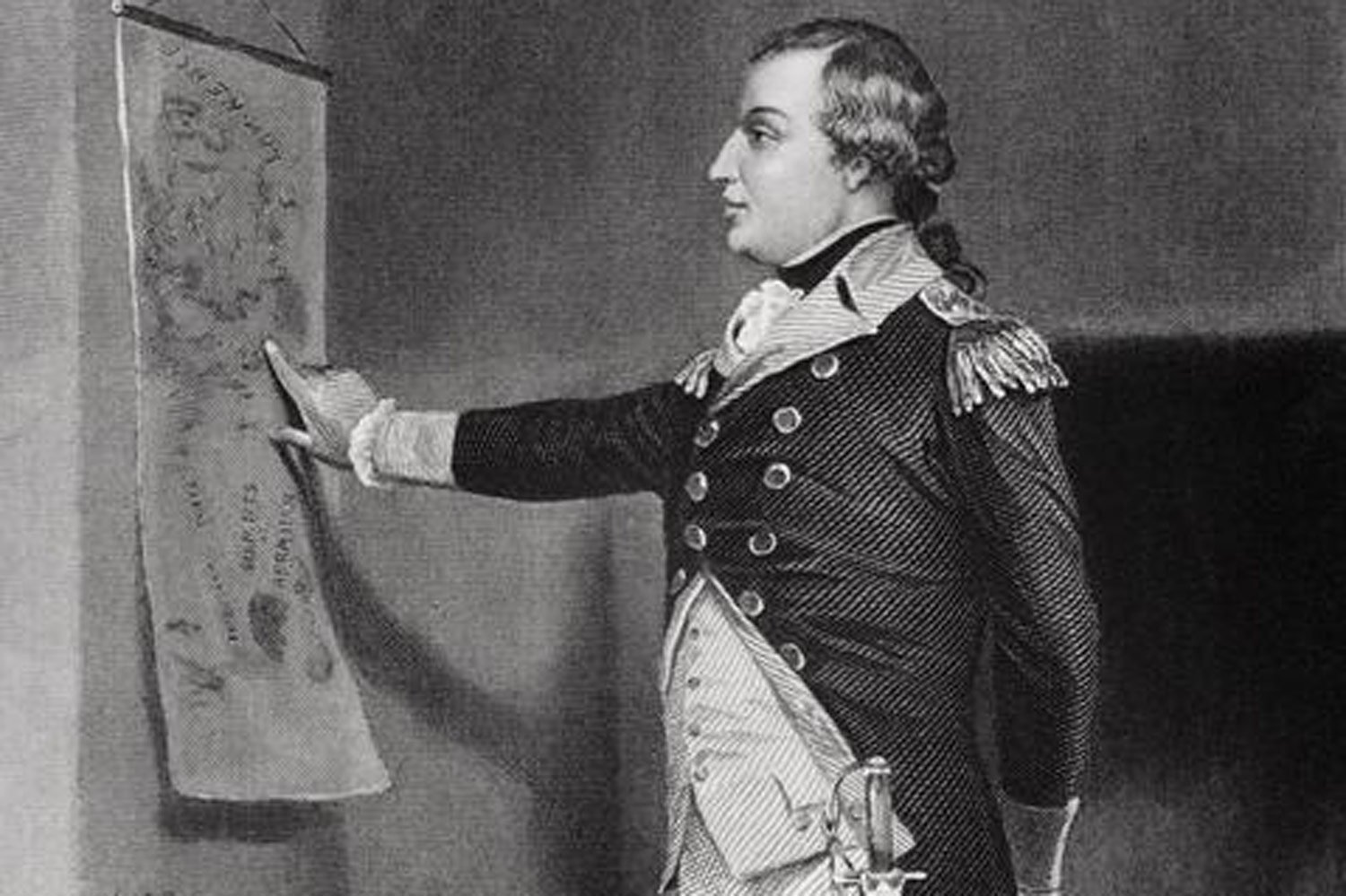

General Guy Carleton, the man in charge of British forces in Canada, chose to return to the safety of Quebec’s walls after repelling the American assault on the city instead of venturing out and attacking the remaining Americans. With the death of General Richard Montgomery, Colonel Benedict Arnold assumed command of the American army outside Quebec and, despite the setback, refused to give up on the conquest of Canada.

American forces still controlled Montreal and much of the area along the St. Lawrence River. Arnold continued to maintain the siege of Quebec, but it was ineffective due to the lack artillery and men. He requested Congress send replacements to bolster his diminished ranks, but it was the dead of winter and only a trickle of new enlistees arrived. To make matters worse, smallpox began to spread through the ranks and many men were unfit for duty.

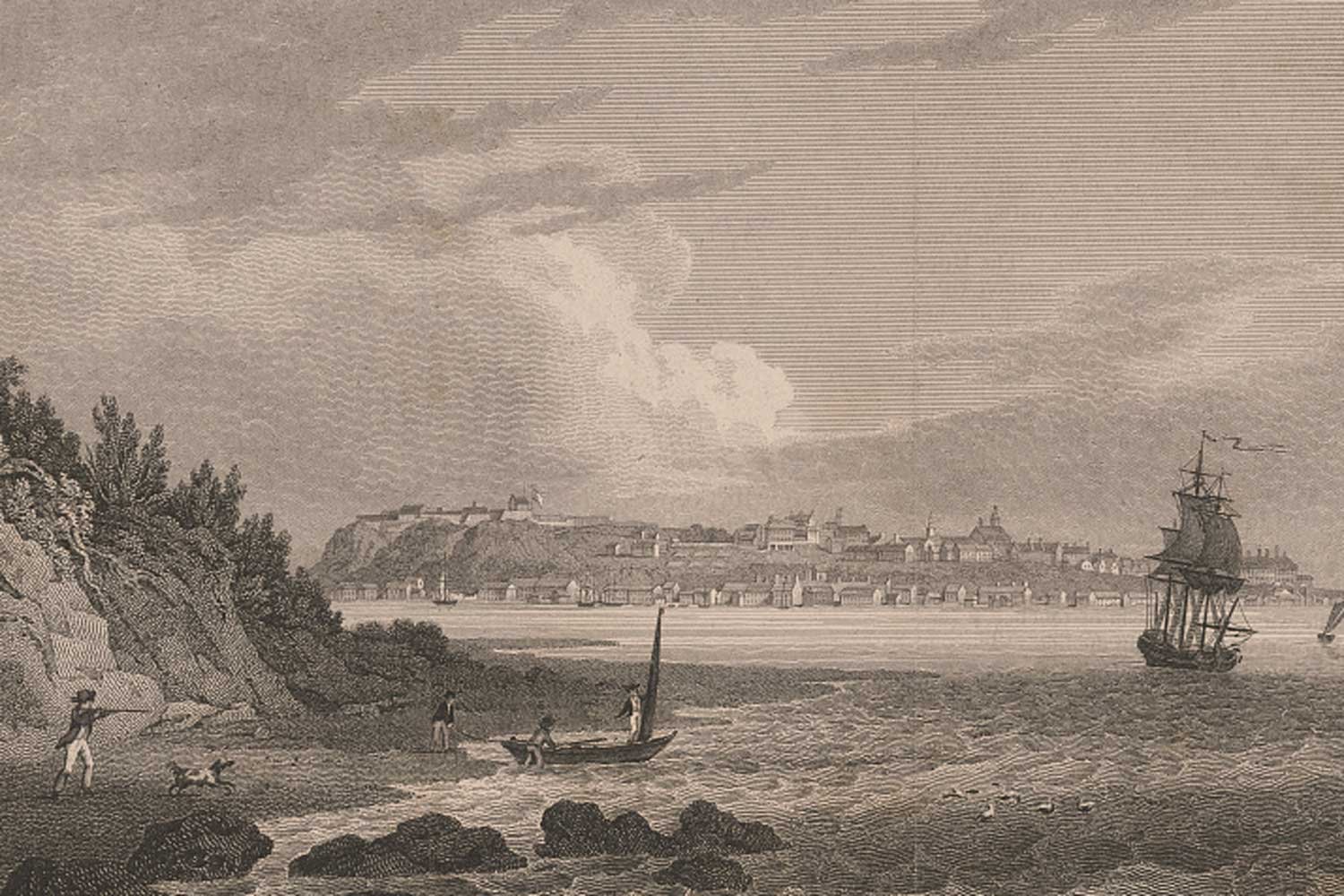

When General John Thomas, Montgomery’s replacement, arrived on May 1, 1776, he recognized the condition of the American camp rendered a siege impossible, and began to plan his retreat from Quebec. Moreover, the river was thawing and reinforcements from England would soon be sailing up the St. Lawrence.

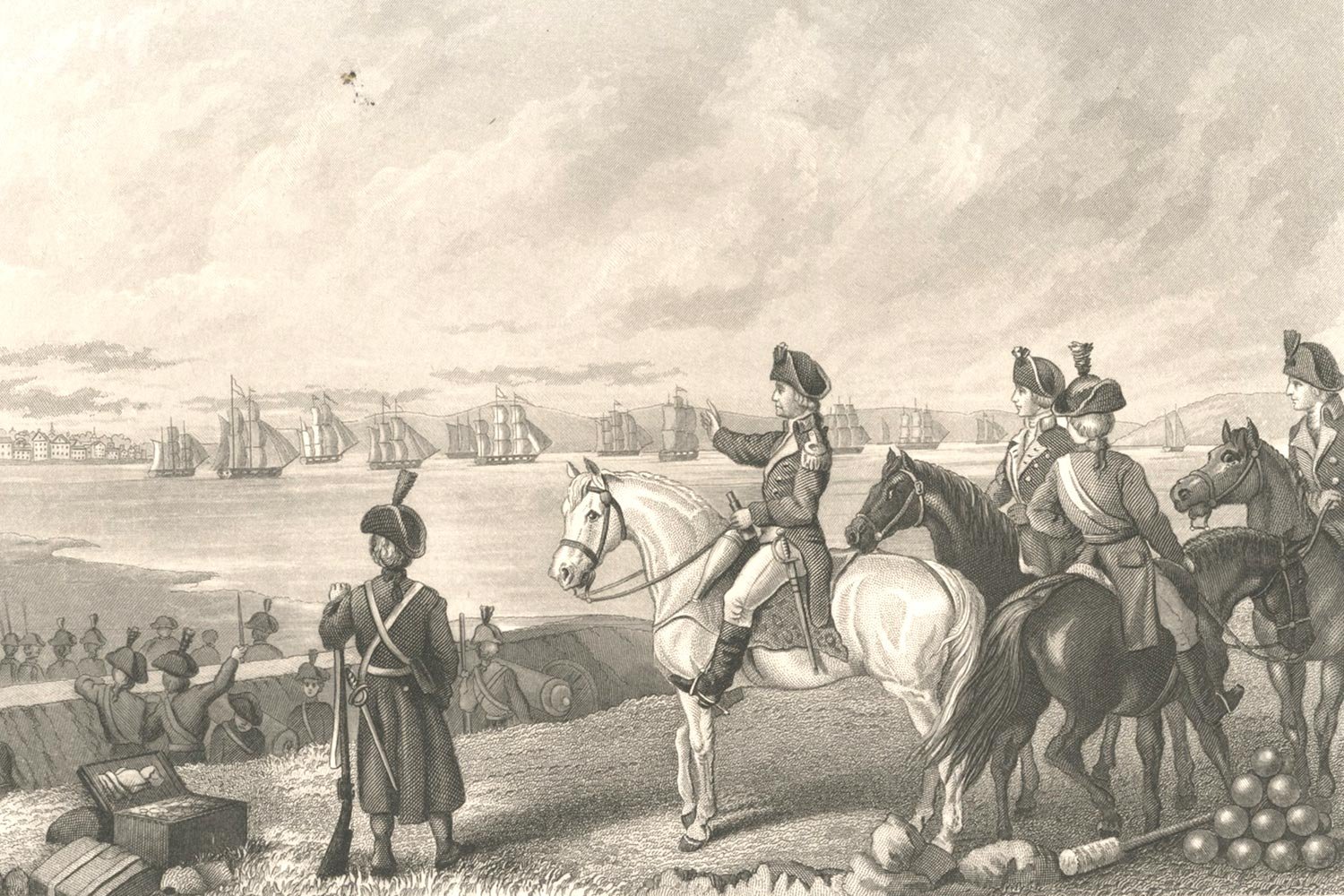

On May 6, the first ships bearing more Redcoats arrived at Quebec and 200 men off-loaded. Carleton quickly moved on the American position and Thomas’ planned retreat became a panicked rout with men leaving behind their cannons and gunpowder. Over the next few weeks, more and more British soldiers arrived, and Carleton pushed further upriver towards Montreal.

On June 2, General Thomas died of smallpox and was replaced by General William Thompson whose command was short lived as he was captured by the British only six days later. General John Sullivan, a very capable officer from New Hampshire, took over and, on June 14, 1776, he began the army’s long retreat from Canada.

Colonel Benedict Arnold, who was in charge of the remaining men at Montreal, arrived with them at Fort St. John, thirty miles south, on June 17. This fort had captured by Americans the previous autumn, when their hopes for conquering Canada had been so high. Now, it was the final American supply depot in Canada, and had to be destroyed before it fell into enemy hands.

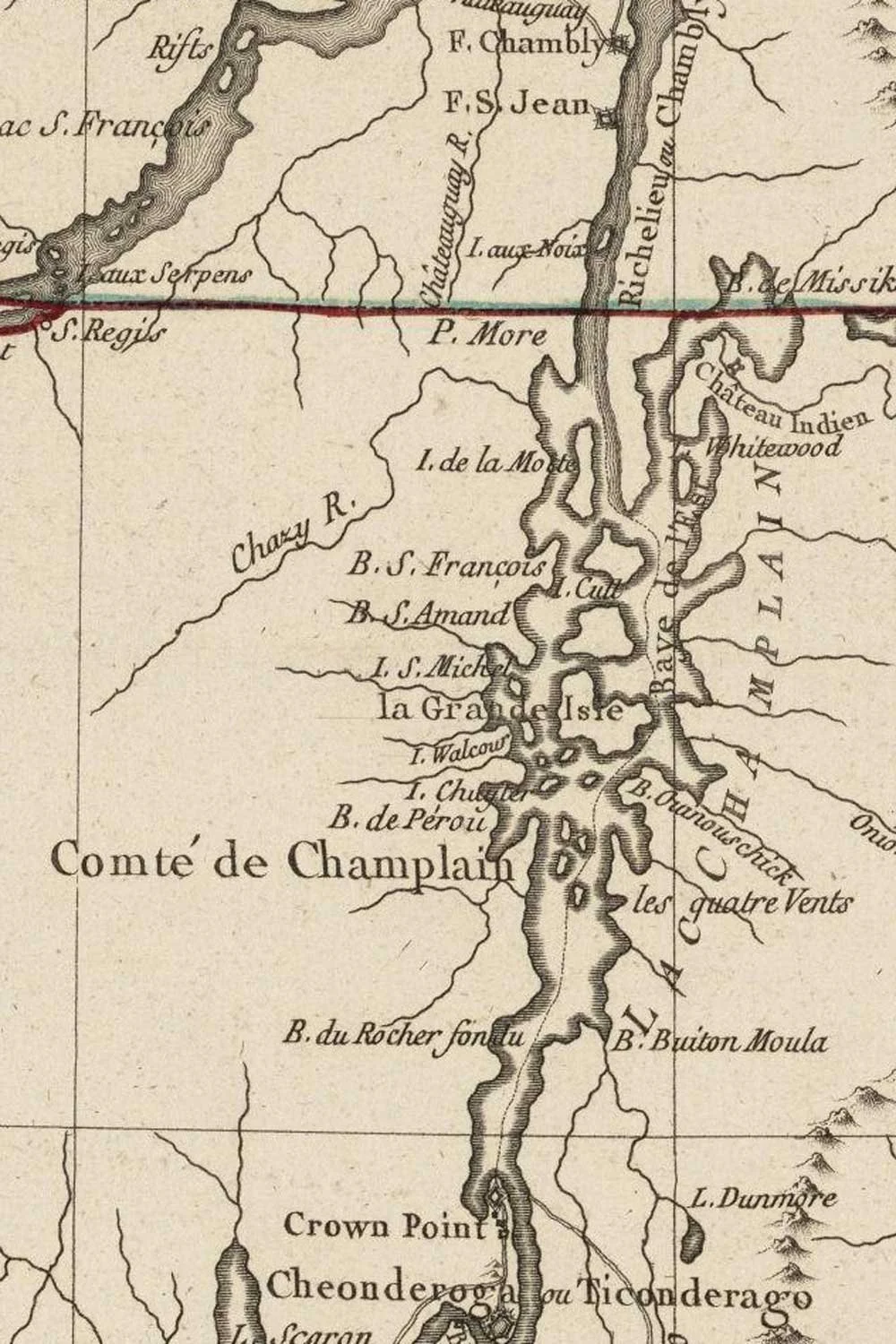

Champlain Valley 1777.

Sullivan entrusted Arnold, his best field commander, with leading the army’s rear-guard action and delaying the British long enough for the main body of the army to make its escape up the Richelieu River to Lake Champlain and eventually to Fort Ticonderoga.

Arnold performed his role brilliantly, destroying all supplies that could not be carried away and burning every building to the ground. He also burned or sank any boats the Americans were not using in their retreat. This delaying tactic forced the British to build their own vessels before they could continue their pursuit since there were no roads suitable for an army in this remote wilderness.

On June 18, Arnold was the last man to get into the last boat leaving Fort St. John, just minutes ahead of the vanguard of the British army. After dismounting from his horse, Arnold removed the saddle and bridle, shot the horse in the head so the British could not have it, and then shoved off.

Now, it was Carleton’s turn to be the aggressor. He had 10,000 men at his disposal with which to pursue his American adversaries. Since roads were non-existent in this area, Carleton planned to sail them across Lake Champlain and then march to the upper reaches of the Hudson River Valley. Securing this area would allow his forces to link up with General William Howe’s army that had just captured New York and Long Island and would effectively separate New England from the rest of the colonies.

However, he had no means of transporting his army across the 107-mile length of Lake Champlain. He also had to deal with a small, but potentially troublesome American fleet that Arnold and Ethan Allen had built soon after they had conquered Fort Ticonderoga the previous spring.

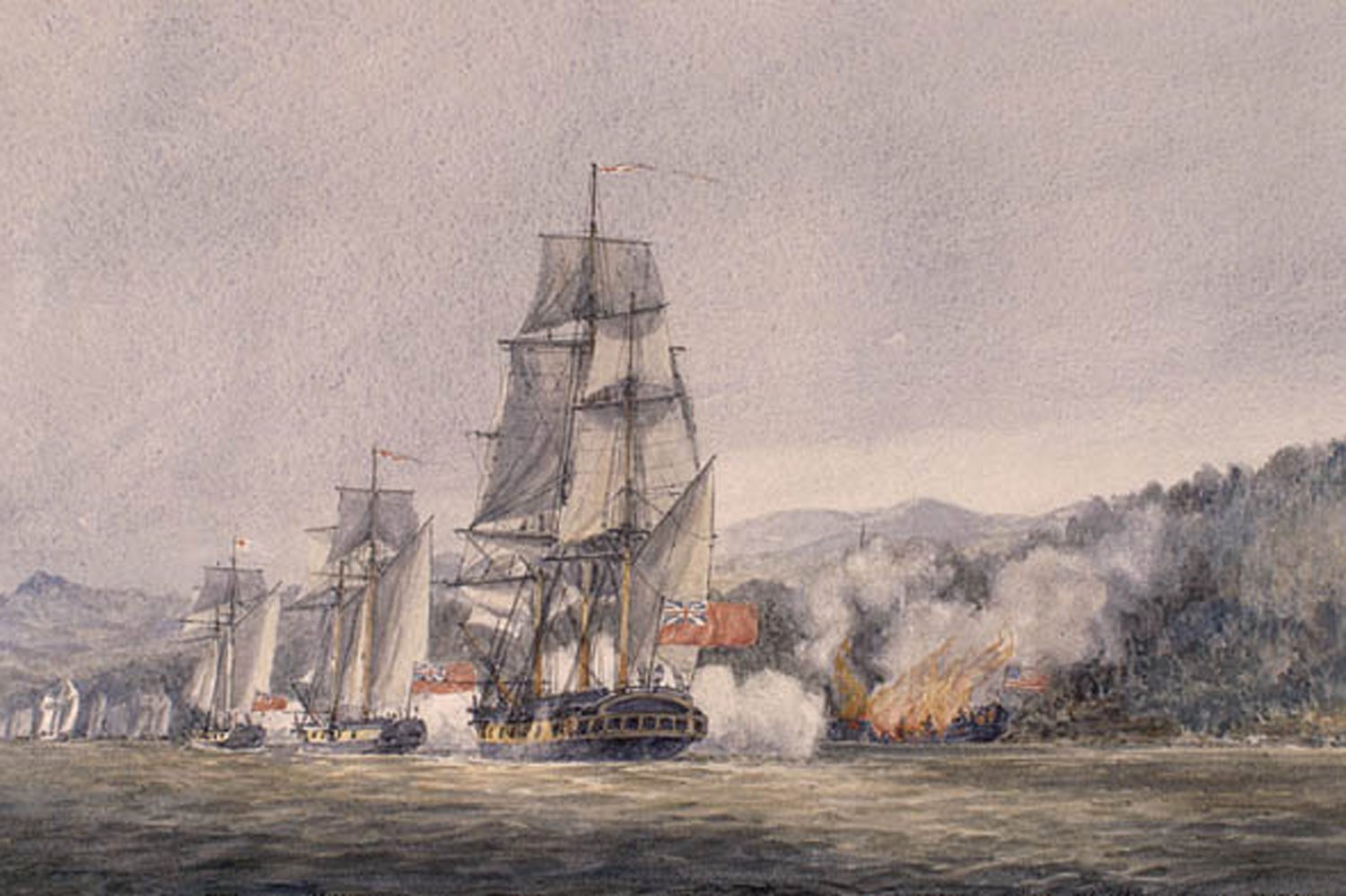

Carleton put his shipbuilders and other men to work creating a fleet of vessels large enough to transport the troops across the lake, as well as a few warships to provide protection from the American gunboats. He even had his men disassemble an entire sloop, HMS Inflexible, an 18-gun ship that could dominate anything the Americans could put afloat.

By October 7, 1776, Carleton had adequate ships to proceed south from Fort St. John up the Richelieu River and resume his pursuit of the Americans. The British flotilla arrived on Lake Champlain two days later, but Carleton would discover Benedict Arnold still had a bit more fight in him.

Next week, we will discuss Benedict Arnold’s brilliant rear-guard action at Valcour Island. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

This article is the seventh in an eight-part series.

Despite his early successes of capturing Fort Ticonderoga and defeating the American rear guard at both Hubbardton and Fort Anne, Burgoyne now faced the greatest adversary of an army invading a foreign land: a lengthening supply line. As Napoleon remarked, an army marches on its stomach and the British soldiers were no exception.