Benedict Arnold and the Perilous March to Quebec

Benedict Arnold’s expedition to the gates of Quebec City in the fall and winter of 1775 is widely regarded as one of the greatest military marches in history. Arnold, despite his sullied reputation due to his traitorous behavior later in the war, was one of America’s most gifted field commanders, and his tremendous leadership skills were put to the test on this perilous journey.

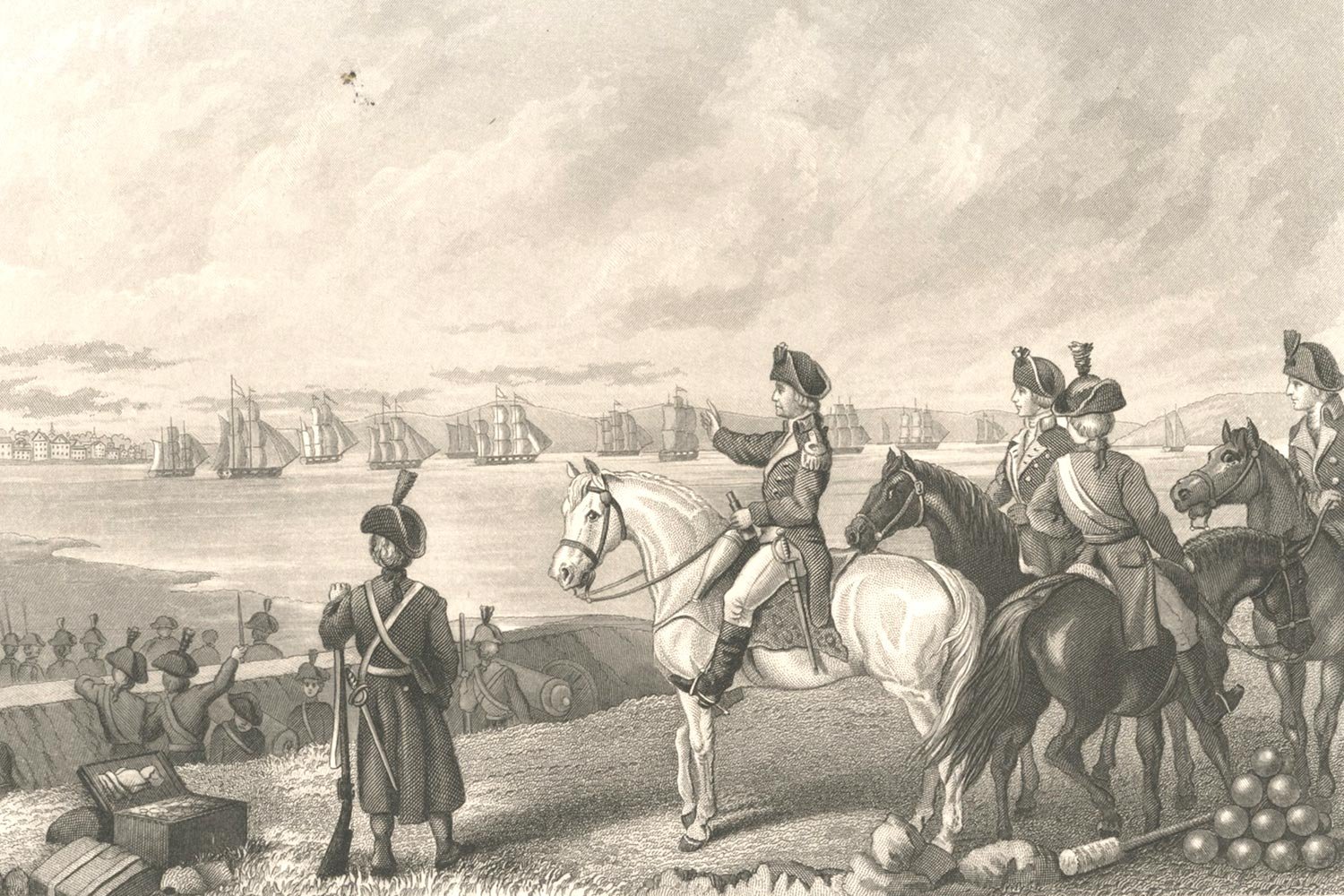

Arnold had been recently commissioned a Colonel and given command of a 1,100-man unit tasked with advancing through the wilderness of Maine to attack the Canadian city of Quebec. Arnold’s force was to support a larger army commanded by General Richard Montgomery that was advancing north along the Lake Champlain corridor to Montreal.

Interestingly, the troops assigned to Colonel Arnold included several men who would become notable in American history. Captain Daniel Morgan commanded about 250 riflemen from the backwoods of Virginia and Pennsylvania and, as a General in 1781, would lead American troops to one of its greatest victories at the Battle of Cowpens. Amazingly, the wives of two of Morgan’s Pennsylvania riflemen also joined the procession.

Captain Henry Dearborn led a militia company composed of New Hampshire farmers on the expedition and would become Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson and the Commanding General in the War of 1812.

Private Aaron Burr set aside law studies to join Arnold’s troops and would become Vice President in 1800 and, four years later, kill Alexander Hamilton in the most famous duel in American history.

“A view of the rivers Kenebec and Chaudiere, with Colonel Arnold's route to Quebec.” New York Public Library.

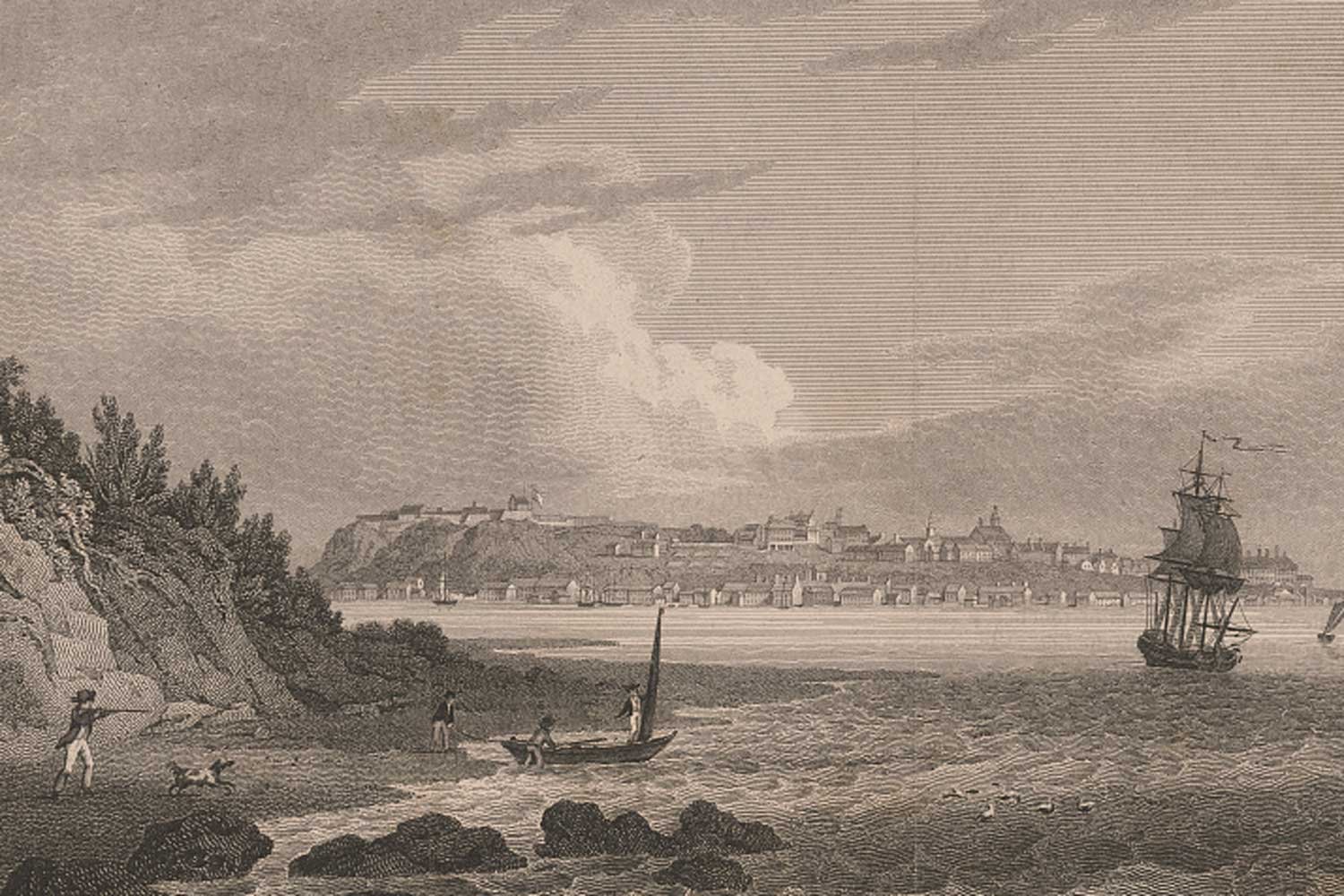

Arnold’s plan was to sail a force from the Boston area to the Kennebec River in Maine, and then up the Kennebec as far as Fort Western (present day Augusta, Maine), past which sailing ships could not go. From there, he would take his men up the Kennebec in bateaux (flat bottomed boats), across a portage known as the Height of Land to Lake Megantic, and then down the Chaudière River to the St. Lawrence River and the gates of Quebec.

Maps for this area were sketchy at best and based on a 1761 journal of a British military engineer. Unfortunately, no one in Arnold’s party had ever traversed this route, which was believed to be about 180 miles. Based on unproven assumptions, Arnold estimated the journey would take about 20 days, which would put the army in front of Quebec City just ahead of the brutal Canadian winter.

Arnold and the main body left Fort Western on September 25, 1775, in their little flotilla of boats, hastily constructed by Reuben Colburn, a local boat builder. Due to the narrowness of the river and the time it took to load each boat, the band of men was stretched out for miles on the Kennebec. Each vessel had two pairs of oars and the idea was to simply row upstream and portage as needed. Within two days, the Kennebec would prove this concept to be a fantasy.

To negotiate around the countless rocks in the river, the entire four-to-five-man crews had to wade in the frigid waist deep water, half pulling and the other half pushing the boats upstream. After only twenty miles on the Kennebec, at Taconic Falls, the men faced their first portage.

The process of portaging began with the crew unloading all provisions in the boat, including the 250-pound barrels of salted beef. They then hoisted the 400-pound rowboats onto their shoulders and carried them along the muddy riverbank, slipping in their waterlogged moccasins and tripping on countless roots and vines, until they found navigable water about a mile away. Next, they returned for the provisions and carried them along this same path, reloaded the boat, and started off again.

“On the last portage of the Great Carrying-Place.” Library of Congress.

Almost immediately, the boats began to leak, and water filled their bottoms. Besides the obvious discomfort to the men, the water ruined the gunpowder and washed the salt off much of their preserved meat which quickly spoiled. In less than two weeks, the men were on half-rations, and even that proved to be wishful thinking. Additionally, they were almost constantly wet from wading in the river and colds and dysentery set in.

On October 2, the men reached the Norridgewock Falls, about forty-seven miles above their starting point at Fort Western. Here, the Kennebec River dropped ninety feet in a series of falls and dangerous rapids, and the only way around it was to carry everything (boats, remaining barrels of food and gunpowder, tents, personal effects) uphill for a fatiguing mile and a quarter.

It was not until October 9, after a week of brute, back-breaking work, that the portage was completed. Two days later, they arrived at the Great Carrying Place, a thirteen-mile-long portage that would take them from the Kennebec to the first navigable portion of the Dead River, one of its tributaries, and the next leg of their journey to Canada. They did not know it at the time, but they had almost 300 miles to go.

Next week, we will continue our discussion of Benedict Arnold’s march to Quebec. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

This article is the second in an eight-part series.

Despite his early successes of capturing Fort Ticonderoga and defeating the American rear guard at both Hubbardton and Fort Anne, Burgoyne now faced the greatest adversary of an army invading a foreign land: a lengthening supply line. As Napoleon remarked, an army marches on its stomach and the British soldiers were no exception.