Benedict Arnold’s Army Reaches Quebec

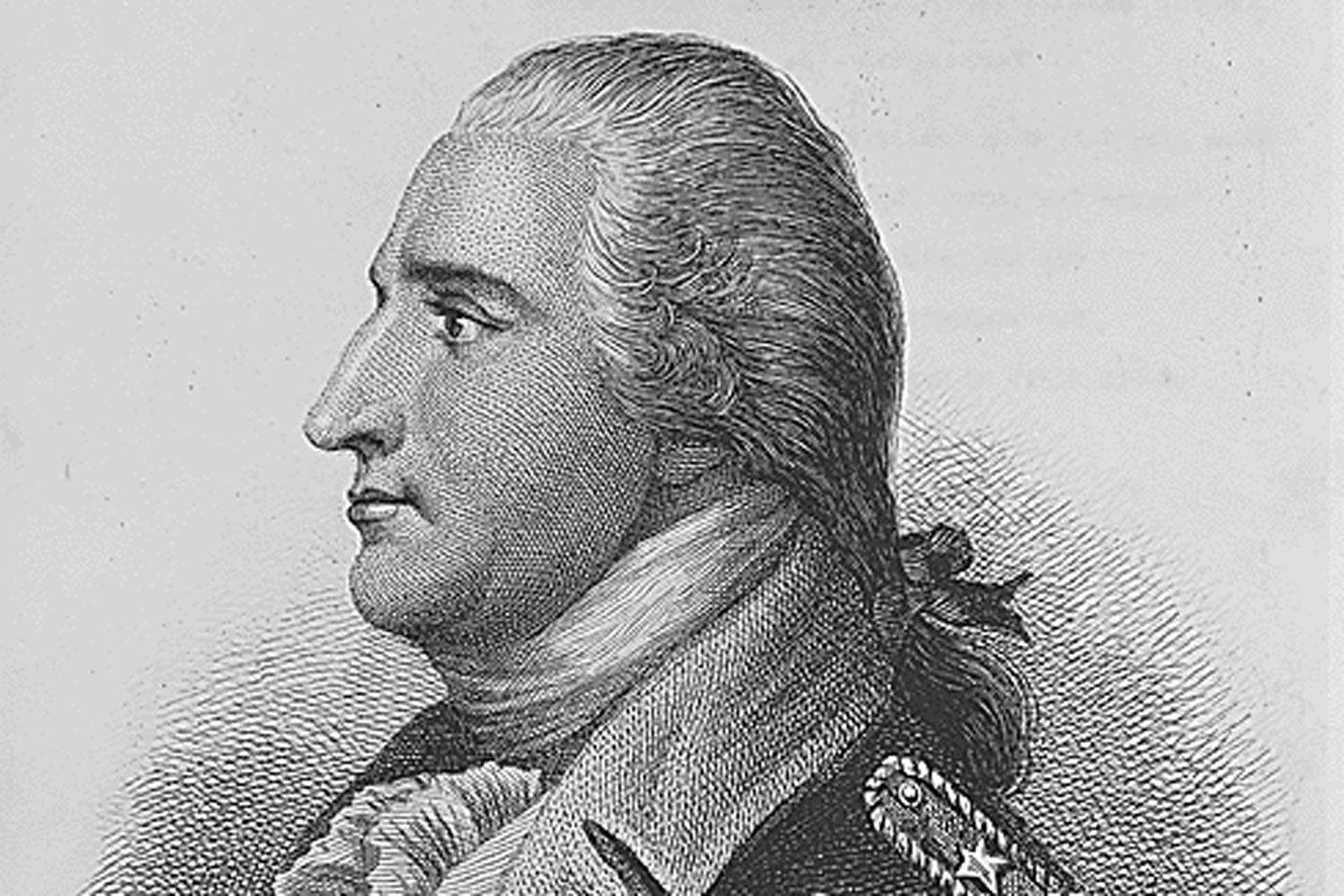

After clearing the Height of Land, Colonel Benedict Arnold’s army on its way to capture Quebec City believed they were on the downhill slope to their destination, but their hardships were not finished. The area which they just entered was poorly mapped, and Arnold’s regiments paid the price for this lack of knowledge.

The men soon wandered into a large swamp that no one knew was there. For two full days, they tried countless paths that appeared to take them out of this muddy maze, but none worked. To stay dry and out of the muck, they spent their nights in trees or on small pieces of slightly elevated ground.

With Arnold well ahead of the main body trying to find food for his men, all sense of unit cohesion and leadership was gone. The officers were as lost as the rank and file, and the 650 men and two women began to lose heart.

One Connecticut private later stated, “The top of the ground was covered with a soft moss, filled with water and ice. After walking for a few hours in the swamp we seemed to have lost all sense of feeling in our feet and ankles. As we were constantly slipping, we walked in great fear of breaking our bones or dislocating our joints…to be disabled from walking was sure death.”

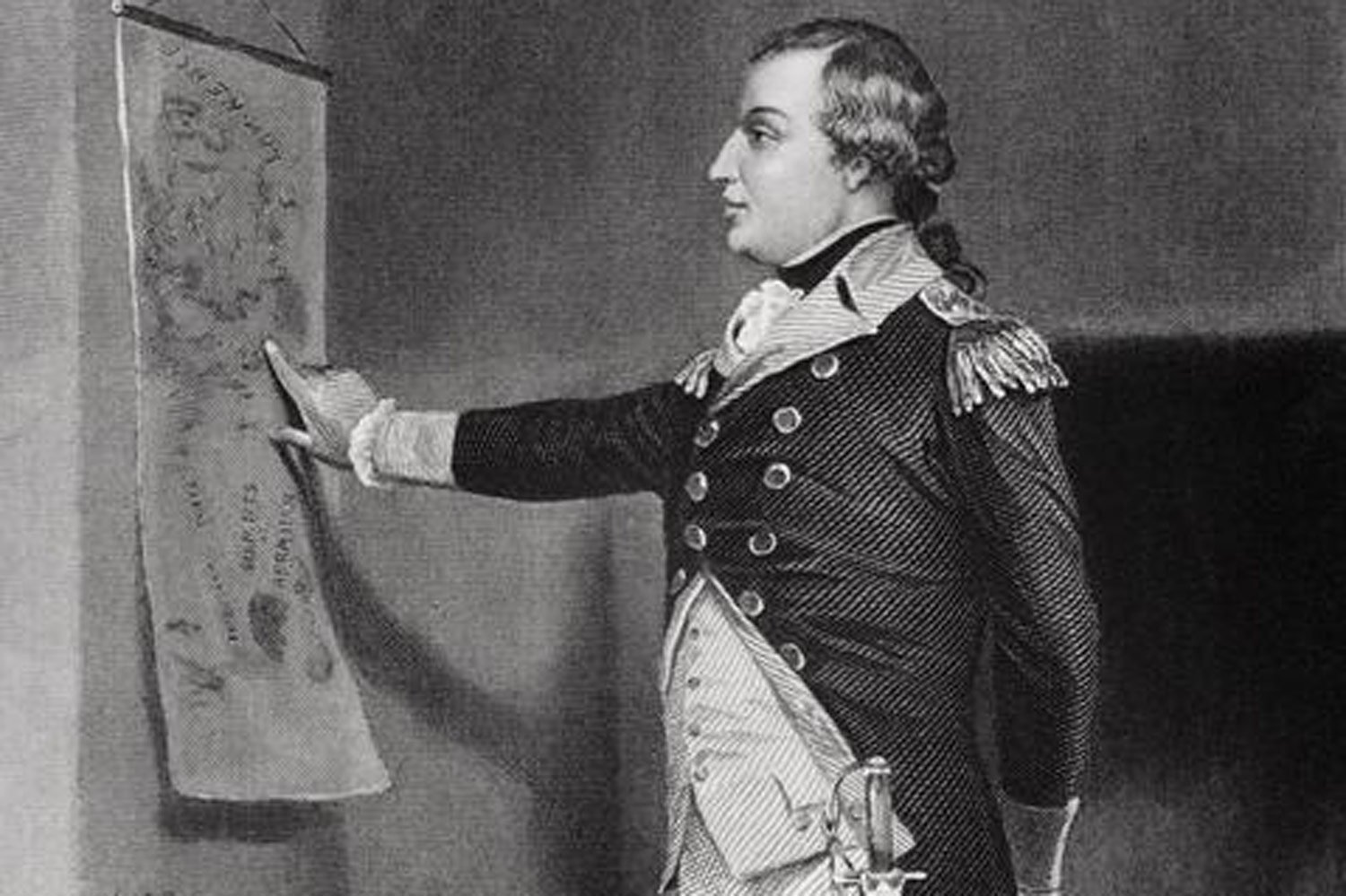

Finally, the intrepid Captain Daniel Morgan rescued the men in boats he had insisted his company of Virginia riflemen men haul over the Height of Land. He was the only commander to do so as all other leaders had abandoned their boats due to the effort involved in carrying them.

Charles Wilson Peale. “Daniel Morgan.” Independence National Historical Park..

The reoriented men were rowed across Lake Megantic, the source of the Chaudière River, the next leg of their journey, and they began their descent. At last, they were on a river going in the right direction.

Unfortunately, the Chaudière was a turbulent river, its name means cauldron or boiling in French. Late on October 31, three boats with most of the remaining provisions overturned and several lives were lost. The men seemed to be at the end of their ropes and began dropping out along the trail. They had no boats, no tents, and had not eaten for two days or more.

Men were now reduced to eating almost anything they could find, including shaving soap, candles, and leather from their cartridge boxes. The New Hampshire farmers in Captain Henry Dearborn’s militia company even convinced Dearborn to let them eat his Newfoundland dog.

Somehow, the men continued forward. On the morning of November 2, they were greeted by the sight of a small herd of cattle being led by some of the advance party sent ahead to forage for food. Arnold had made it.

The cattle were slaughtered and roasted on the spot, tobacco was distributed, and hot oatmeal served up. Additional food was taken further back up the trail to those that had been too weak to continue. All day long stragglers wandered into the encampment, thankful to be alive. After a day of rest, the men were on the move again.

Arnold’s army was soon in the midst of the French-Canadian villages strung out for miles along the Chaudière, about seventy miles south of the St. Lawrence River. Unfortunately, Arnold discovered that while the residents of this area were friendly to the Americans and happy to sell them food and drink, almost all were decidedly neutral. They had no desire become involved in a fight that was not theirs, and Arnold picked up just a few recruits.

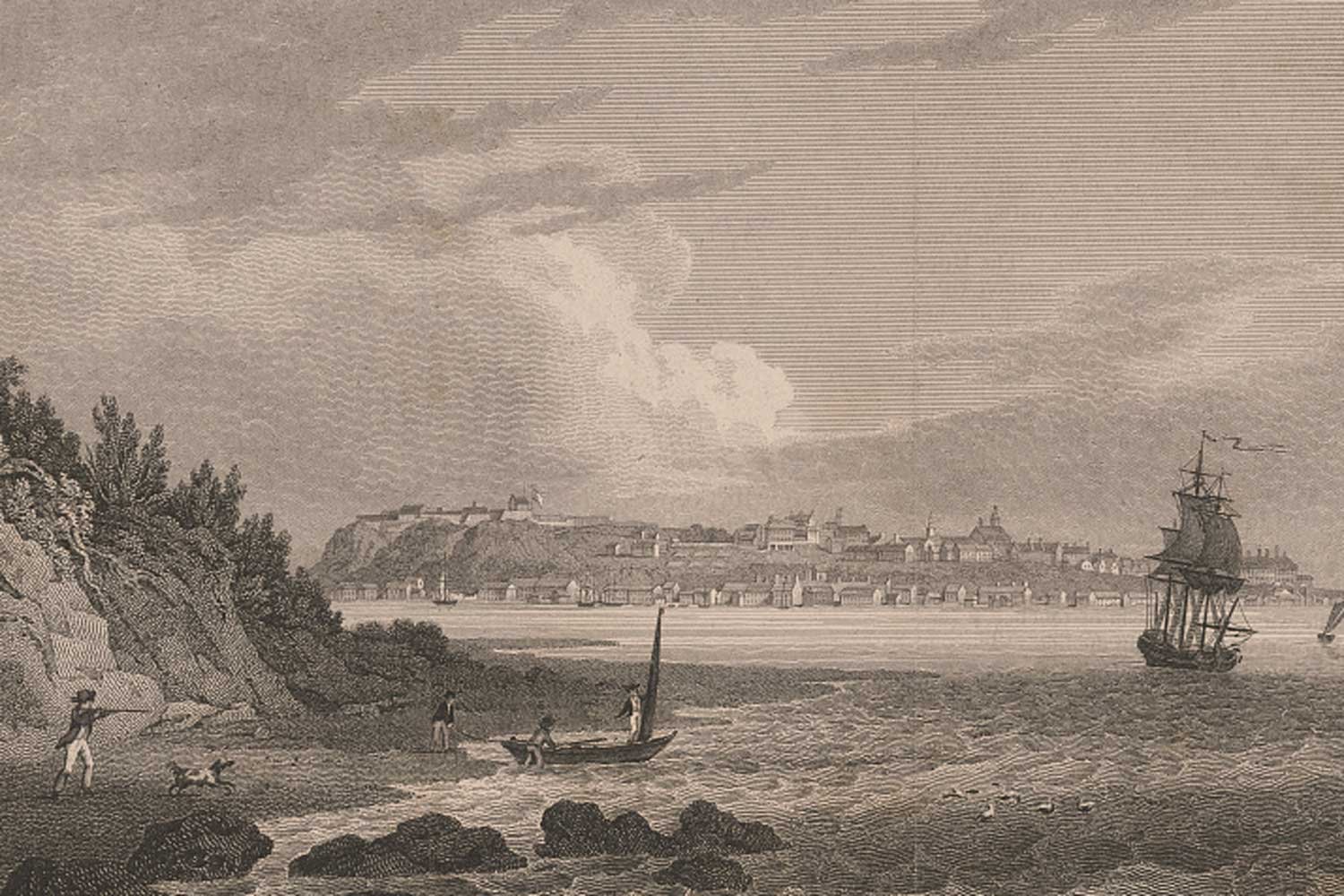

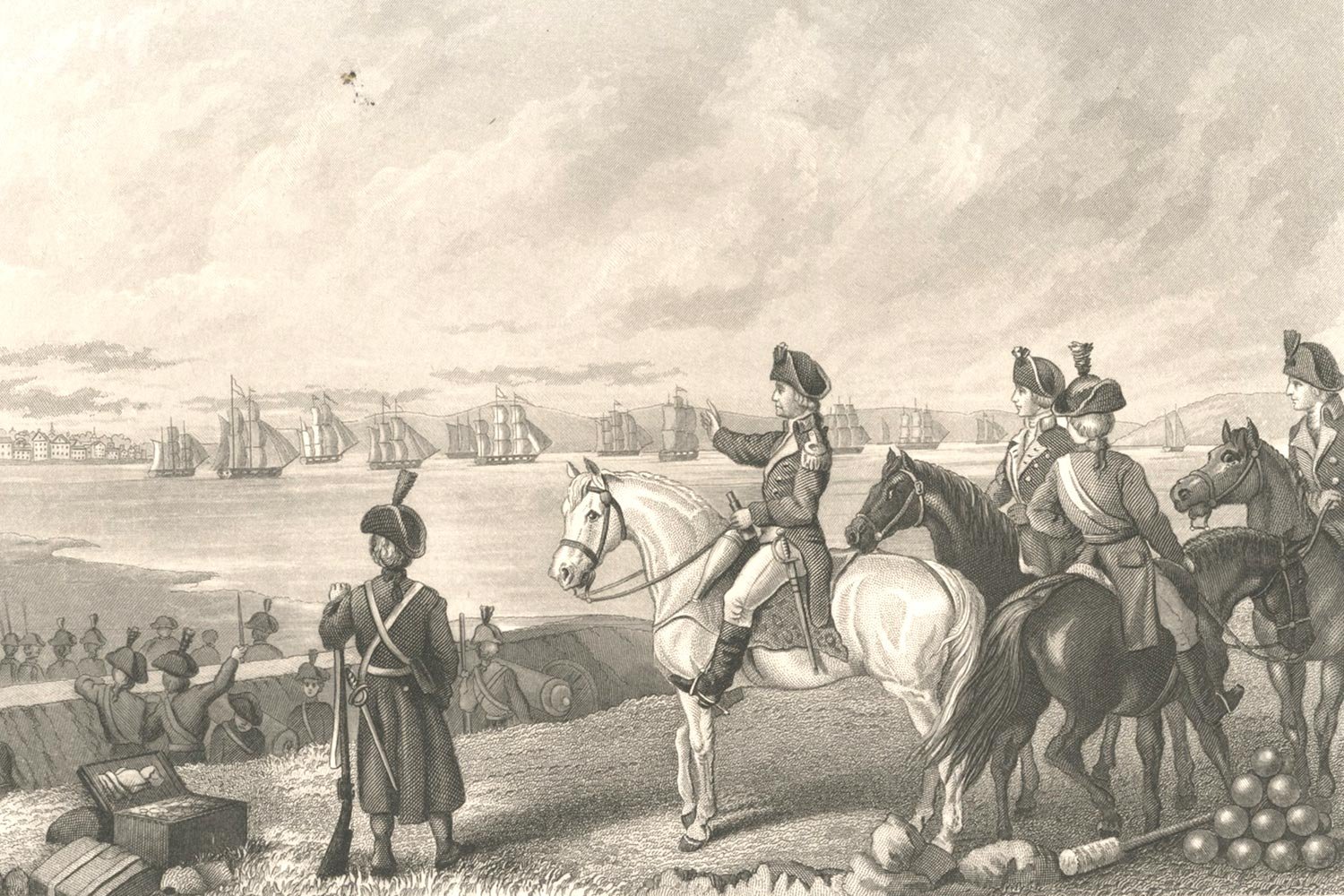

On November 8, lead elements of the Pennsylvania riflemen came to the bluffs at Pointe-Levi, just across the St. Lawrence River from Quebec City, and finally gazed upon their objective. Here, the river was about one mile wide and two large British frigates patrolled the waters under the walls of Quebec City.

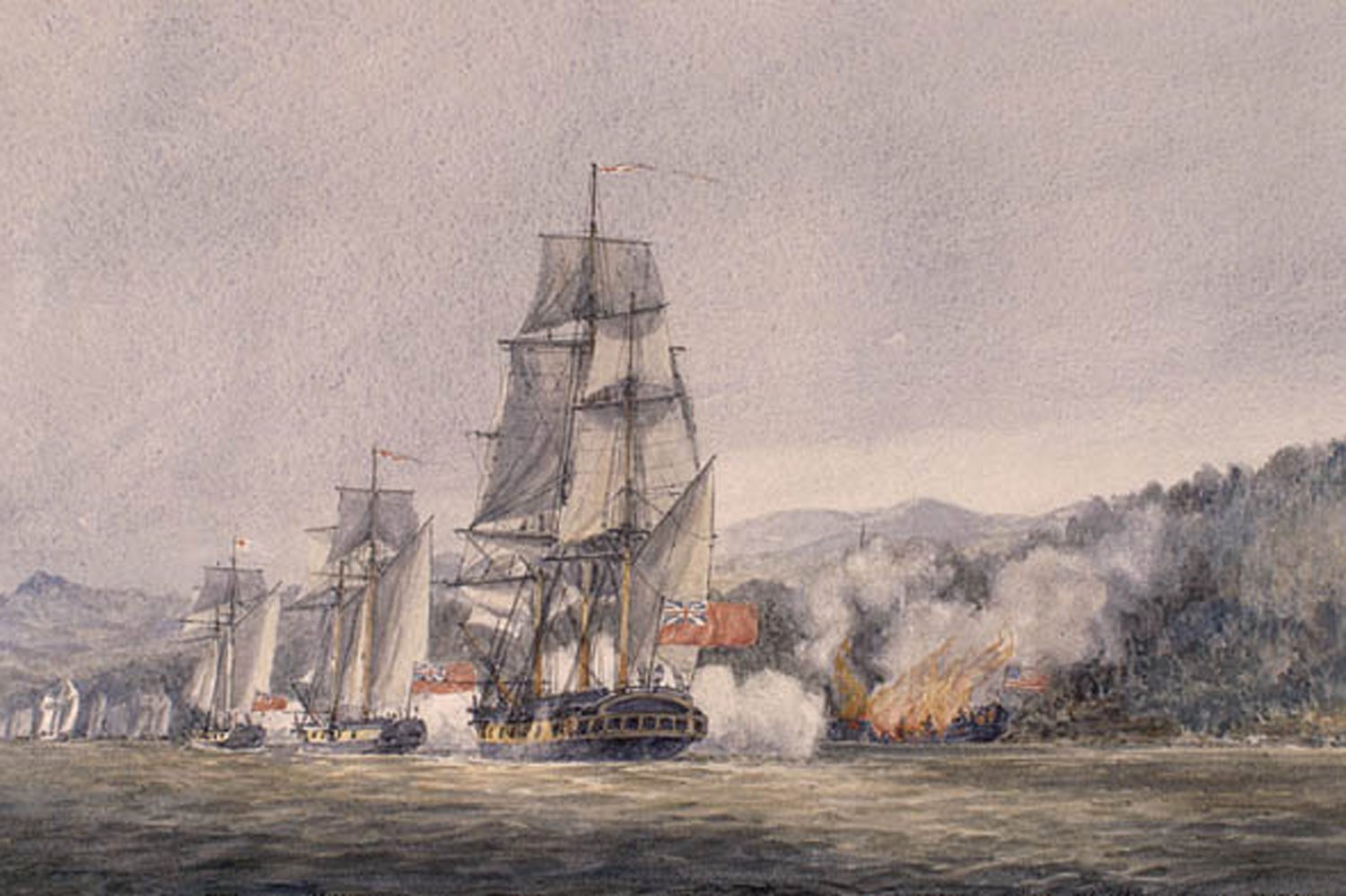

After collecting boats along the riverbank and waiting for favorable weather, the soldiers slipped silently passed the warships the cloud-darkened night of November 13-14. Not surprisingly, the lead vessel held both Colonel Arnold and Captain Morgan. By 4:00am, about 450 of the 650 men had been landed before sentries noticed the gathering Americans, and the crossing was temporarily halted. The rest of the men would follow within a few days.

Forty-five days earlier this group of hardy men had started out from Fort Western on the lower Kennebec River. The march they completed is widely considered one of the greatest in military history. The distance they covered was 350 miles, not the 180 miles originally estimated. The rivers had flowed faster, the heights had been higher, and swamps more extensive than any had imagined. They even endured a freak hurricane that cost them badly needed provisions and time.

The men who completed the trek became known as the “Famine Proof Veterans” and earned the respect of their countrymen. Colonel Benedict Arnold demonstrated his tremendous leadership skills, tenacity beyond measure, and a tactical genius that found solutions to problems. Now, standing on the Plains of Abraham before the walls of Quebec City, British forces under General Guy Carleton awaited their assault.

Next week, we will discuss the opening phase of the siege of Quebec. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

This article is the fourth in an eight-part series.

Despite his early successes of capturing Fort Ticonderoga and defeating the American rear guard at both Hubbardton and Fort Anne, Burgoyne now faced the greatest adversary of an army invading a foreign land: a lengthening supply line. As Napoleon remarked, an army marches on its stomach and the British soldiers were no exception.