Arnold’s Scheme Goes Awry

In June 1780, Benedict and Peggy Arnold asked two old acquaintances who were congressmen from New York, Robert Livingston and Phillip Schuyler, to request that General George Washington give Arnold the command of Fortress West Point. Unaware of Arnold’s true motives and wanting to help their friend, both congressmen complied. Arnold was now certain West Point would soon be his to give away.

Sensing he held a strong hand, Arnold informed Sir Henry Clinton that with West Point as the new prize, the price for his deception would be twenty thousand pounds, not the ten thousand previously discussed, and a command in the British Army. On July 24, Clinton agreed to meet these demands.

One week later, Arnold met with Washington at his Excellency’s headquarters in New Haven. Washington informed Arnold that he had great news for his stalwart battlefield general. Arnold was to be entrusted with a most prestigious position, but it wasn’t West Point. Arnold was to be given the command of the critical left wing of the Continental Army in the next campaign against the British.

Arnold was stunned, but not in a good way. As Washington later remembered, Arnold “appeared quite fallen, and, instead of thanking me, never opened his mouth.” Arnold returned to his quarters and aides reported him pacing back and forth and seeming out of sorts. Back in Philadelphia, Peggy also did not take the news well, reportedly going into hysterics when informed of this “great honor” for her husband.

Arnold, who saw his grand scheme falling apart, told Washington he was still too weak for field duty and begged him for the desk-bound West Point position. To say Washington was shocked would be an understatement. Three years earlier, Arnold had been the most aggressive battlefield commander in the Continental Army, intrepid almost to rashness. Washington reminded him that the injury to his leg had happened three years ago, but Arnold would not relent.

On August 3, Washington learned that the French would not be assisting the Continental Army that summer and, therefore, the campaign was off. Feeling that Arnold deserved a soft assignment for all he had done to help the American cause, Washington awarded Arnold the command of West Point.

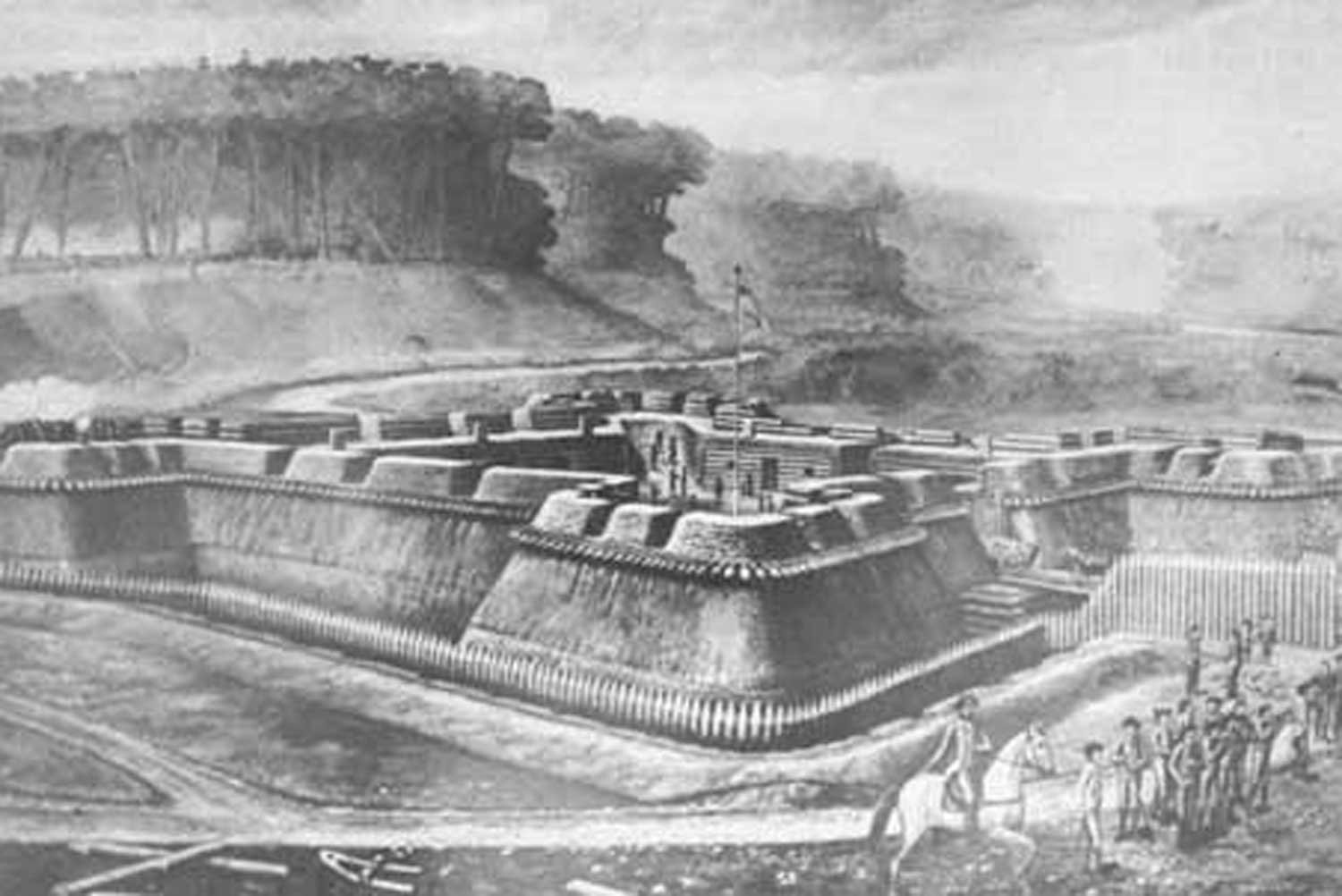

Arnold raced to his new command post and quickly took steps to weaken the fort’s defenses by assigning most of the soldiers to trivial work details and leaving very few to actually bolster the fort’s defenses. Colonel John Lamb, Arnold’s top subordinate, questioned the commander on the work assignments but Arnold held fast.

Knowing Peggy would need to flee with him after his treachery was exposed, Arnold sent an aide to Philadelphia to escort her to West Point. He also sent word to Clinton that the dye was cast and the fort would soon be his for the taking. Clinton began organizing his troops for a movement north to West Point, but requested a face-to-face meeting between Major John Andre, his spy chief, and Arnold, to ensure that Arnold was truly who he said he was.

C.F. Blauvelt. “Treason of Arnold Arnold persuades Andre to conceal the papers in his boot.” Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, on September 17, General Washington visited West Point on his way to confer with French General Rochambeau in Connecticut. Washington was concerned with the condition of West Point’s defenses and Clinton’s increased troop activity in New York. He informed Arnold he would stop again on his way back about a week later.

Arnold moved quickly and arranged to meet with Major Andre on the west side of the Hudson about 20 miles below West Point. On the evening of September 21, he hired two local farmers, the Cahoon brothers, to row a boat to the British ship HMS Vulture anchored down river with Andre waiting on board. Although the Cahoons did not want the job, Arnold brow beat them into going and they delivered Andre around 2:00am.

Arnold and Andre conferred until 4:00am and then Arnold ordered the Cahoons to row Andre back, but the Cahoons were tired, and the farmers refused to go until they got some sleep. Their need for rest would have momentous consequences. A few hours later, cannons were heard firing in the distance. It turned out to be an American shore battery driving off Andre’s waiting ship but without their precious cargo.

Andre now had no alternative but to make his way back to British lines on horseback, despite the dangers of being stopped by American sentries. Arnold gave Andre a pass made out to John Anderson and returned to West Point while Andre waited until the next morning before heading south towards British lines.

At the suggestion of one of Arnold’s accomplices, Joshua Smith, Andre changed from his British uniform into civilian clothing to aid his escape. Andre knew this was a dicey move because soldiers caught in civilian dress behind enemy lines were considered spies and the standard penalty for spying was a quick hanging from the nearest tree.

At dawn on September 23, with the West Point plans stuffed into his boot, Andre began his journey through the American lines. At 10:00am, as Andre was approaching the Tarrytown bridge and safety, three American soldiers emerged from the bush demanding his papers. Despite the pass signed by General Arnold, Andre was searched, and the sensitive documents found; Andre knew he now had a date with the hangman.

Next week, we will discuss closing scenes of the saga of Benedict Arnold. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, who commanded the unit that had captured the British spy Major John Andre, ordered an aide to take word to General Benedict Arnold about Major John Andre’s capture. He sent another aide to find and inform General George Washington as well.