The Fall of Benedict Arnold

The Benedict Arnold who was named military commander of the Philadelphia region in 1778 was not the same man whose battlefield exploits had made him an early American legend. When Arnold had led his contingent of New Haven militiamen to the siege of Boston in April 1775, he was a wealthy, incredibly athletic man intent on helping the United States gain its independence.

Three years later, Arnold was a bitter man whose personal finances were in disarray and who had become crippled for life while fighting for the American cause. Perhaps worse than his physical injury was his mental state and how he felt about the land for which he had risked his life.

Ironically, as things would turn out, Arnold felt betrayed by his country, especially Congress and many high-ranking officers in the Continental Army. While Arnold had lost his fortune and health fighting for America, others who had done less but were more politically connected received undeserved promotions and accolades. As he took his new position, Arnold had had enough and would now pursue his own self-interest.

In June 1778, Sir Henry Clinton evacuated Philadelphia and marched his Redcoats east towards New York. While General Washington and the Continental Army were in hot pursuit, Major General Arnold, who intended to live lavishly, promptly moved into the Penn mansion which had been used by Clinton as his headquarters. This arrangement did not give a great first impression of Arnold to city residents.

Arnold almost immediately began to use his position to make profitable business deals on the side. He secretly arranged to get a cut from the sale of British and Loyalist goods confiscated when those groups left the city. He also gave passes to help smugglers known to be Loyalist sympathizers evade American privateers for a cut of the profits.

These activities were certainly unethical and probably illegal, but many colonial officials made money from their position, and even smuggling was largely accepted, especially in New England. But, in retrospect, what really did Benedict Arnold in was that he fell in love with the wrong woman.

The Shippen family was one of the most prominent in Philadelphia and suspected of having Loyalist sympathies. Judge Edward Shippen had four daughters, the youngest of which was Margaret, better known as Peggy. She was eighteen, a real beauty, and apparently quite a flirt when Arnold came to town in June of 1778.

Arnold who was thirty-seven and had been a widower for three years, was immediately smitten by the vivacious Peggy. His courtship was like his battlefield tactics, an all-out frontal assault, and Peggy was quickly conquered. After all, what teenage girl could turn down the attentions of a dashing war hero and one of the best-known men in America; the two were married on April 8, 1779.

While there is no record of their initial dinner table conversations, they must have included Arnold’s strongly held opinion that he had been poorly treated by his own country. Peggy, who had been the romantic target of more than a few British officers during their stay in Philadelphia and maintained a correspondence with several of them, probably provided a sympathetic ear to Arnold.

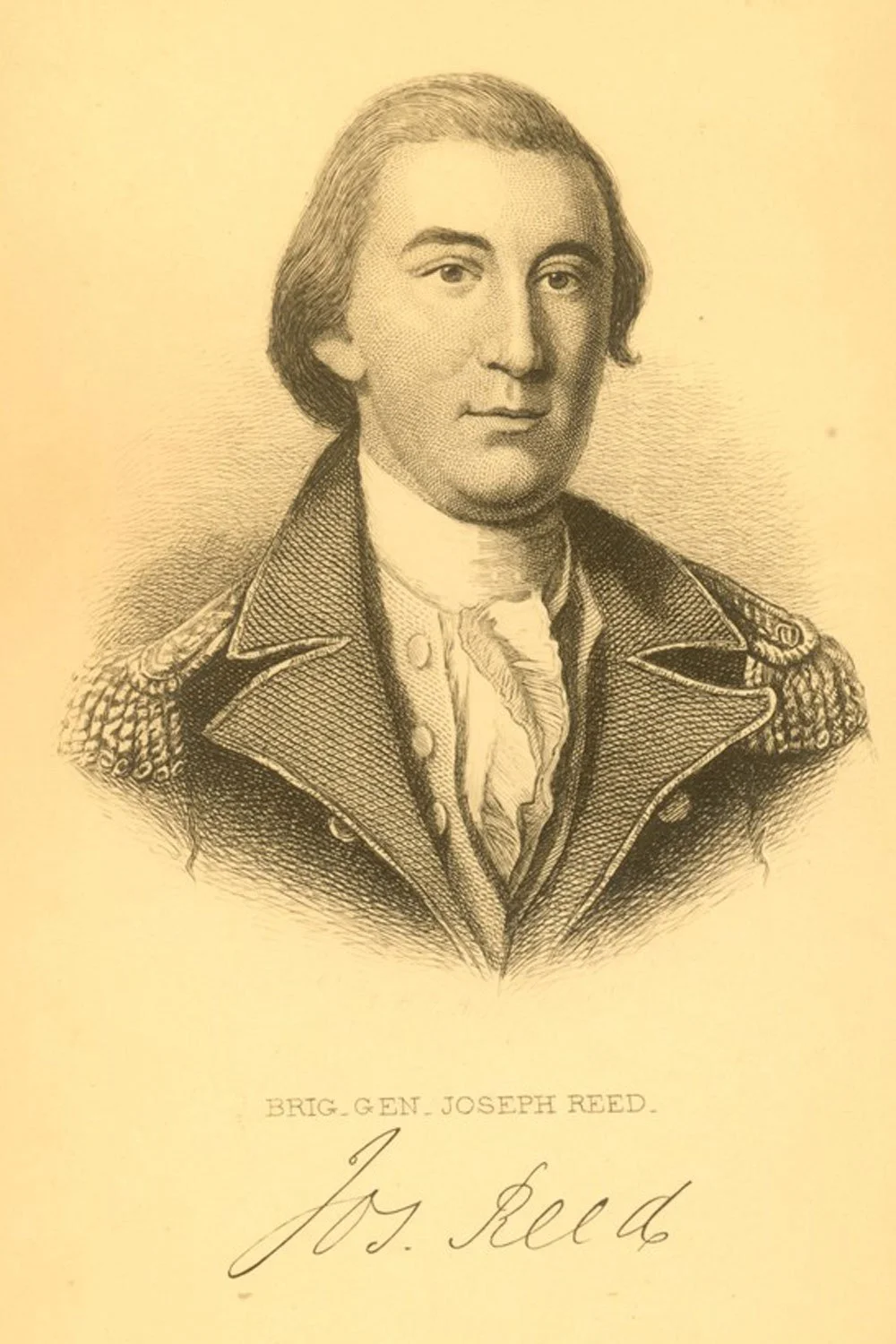

“Joseph Reed.” University of Pennsylvania.

About the same time that Arnold’s courtship of Peggy was taking place, Joseph Reed, the President of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council (essentially their governor), had taken a great dislike to Arnold and publicly accused him of several illegal activities. While most of the charges were frivolous and quickly dismissed by a Congressional committee, two were not and those were referred to General Washington.

Arnold requested that Washington immediately rule on the charges so Arnold could put the matter behind him. However, Washington had received a separate letter from Reed insisting the trial be postponed so he could find more evidence of Arnold’s wrongdoing. Reed further stated that unless Washington agreed to a delay, Pennsylvania would withhold any future support for the Continental Army.

Washington had little choice and agreed to Reed’s demand to postpone Arnold’s trial. This latest disappointment, especially coming from a man he revered, proved to be the breaking point for Arnold.

On May 5, he penned a sharp letter to Washington in which he stated, “Delay in the present case is worse than death…If your Excellency thinks me criminal, for heaven’s sake let me be immediately tried and, if found guilty, executed…Having made every sacrifice of fortune and blood, and become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet the ungrateful returns I have received from my countrymen.”

About the same day Arnold was making this passionate plea to Washington, he wrote another letter and sent it by secret agent to New York. On May 10, about a month after marrying Peggy, the letter arrived at the headquarters of Major John Andre, one of Peggy’s former suitors and the spy chief for the British Army in North America. Its contents contained the startling news that an American war hero wanted to defect.

Next week, we will discuss the betrayal of Benedict Arnold. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, who commanded the unit that had captured the British spy Major John Andre, ordered an aide to take word to General Benedict Arnold about Major John Andre’s capture. He sent another aide to find and inform General George Washington as well.