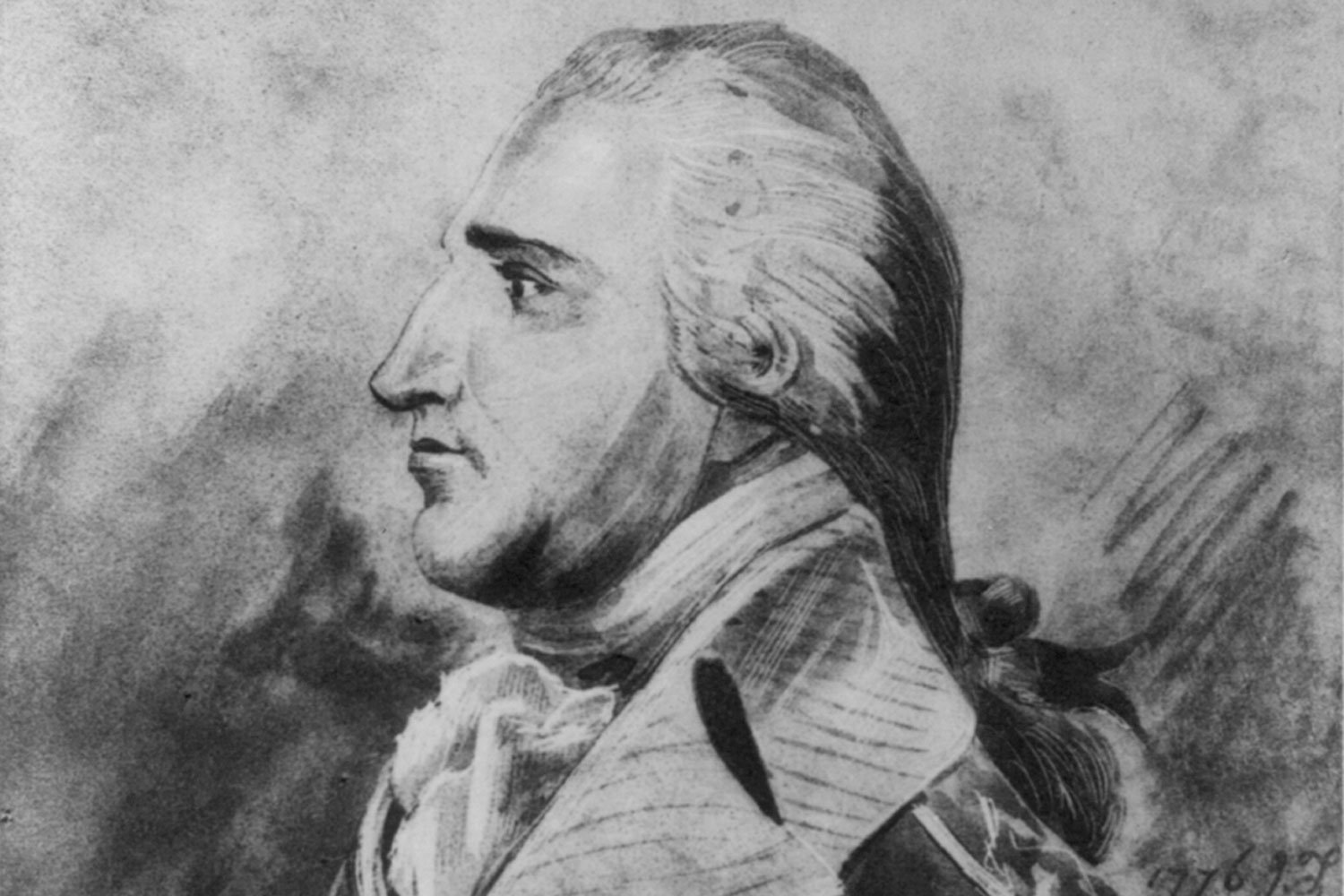

The Hero of Saratoga

General John Burgoyne had captured Fort Ticonderoga on July 6 and was advancing south. General George Washington requested that Congress send his most trusted field commander, Benedict Arnold, to stop Burgoyne. Washington informed Congress that without Arnold “the most disagreeable consequences may be apprehended.”

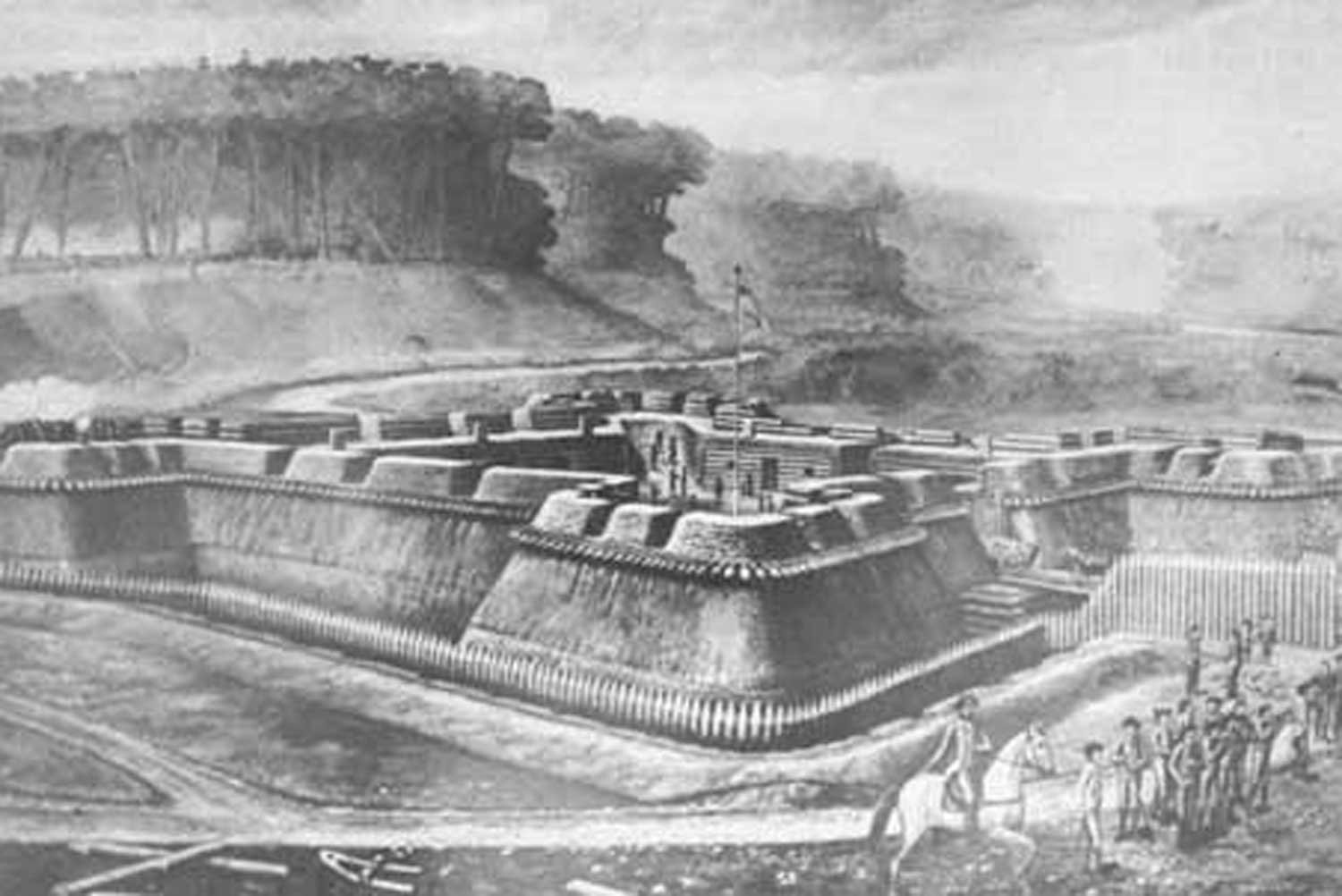

General Arnold went without delay to the American camp north of Albany to assess the situation with General Schuyler. A month later, fate offered Arnold another “save the day” opportunity. Fort Stanwix, the key American installation in western New York was under siege.

Schuyler sent Arnold at the head of 800 men to relieve the fort which he did on August 22, without even firing a shot. Instead of wading into the British force surrounding Fort Stanwix, Arnold used a ruse to get the British to leave. He sent Hon Yost, a suspected Loyalist sympathizer who was being held in confinement and feared for his life, to their camp.

Yost informed the besiegers that the formidable Benedict Arnold was heading their way at the head of 3,000 men. The 900 Indians that constituted half of the army surrounding Fort Stanwix packed up and headed for home that same day.

That task completed, Arnold hurried back to Albany and the American camp still under pressure from Burgoyne. On September 19, Arnold’s maneuvers and battlefield decisions thwarted a British assault at Freeman Farm.

Four weeks later, on October 7, this fearless man led his most consequential assault of his short but illustrious career when he charged and captured a strongly defended enemy redoubt at the Battle of Bemis Heights, ensuring an American victory. Perhaps more importantly, Arnold’s battlefield heroics forced Burgoyne to finally abandon his drive to Albany. Within a week, General John Burgoyne would surrender his entire army, and, with this victory, France would enter the war.

Alonzo Chappel. “Gen. Arnold wounded in the attack on the Hessian redoubt.” New York Public Library.

Although General Arnold was instrumental in winning both battles of Saratoga, General Horatio Gates, the American commander, failed to mention Arnold’s exploits in his official dispatches to Congress. Gates, who would prove to be unscrupulous and even try to undermine Washington’s authority, was jealous of Arnold’s fame and had no intention of adding to it. Not surprisingly, Arnold reacted in a fury and had an ugly confrontation with Gates.

During the engagement at Bemis Heights, Arnold was severely wounded in his left leg, the same one injured at Quebec. The bone was shattered, and doctors recommended amputation, but Arnold refused to give up his leg. Arnold bluntly told the surgeons he would rather die than become a one-legged cripple. His recovery was painful and long and Arnold was confined to his bed for months. The injured left leg ended up two inches shorter than the right and this vibrant, proud man would limp for the rest of his life.

It is likely during this period, the first inactive one of his adult life, Arnold had time to ponder how his life had turned over the past two years. Prior to 1775, Arnold been a robust man, one of the wealthiest men in Connecticut, with a thriving business and a pretty wife that adored him.

Since joining the American cause, his battlefield successes had brought him fame, especially in the eyes of the common man. However, his shipping business had suffered, and he had become crippled in the service of his country. Worst of all, Congress, the ruling body of America, seemed to not appreciate all Arnold had done for his country. That sort of reflection would be enough to embitter most men, and Arnold was no exception.

He finally made it home in May 1778 to a hero’s welcome, but, after only a few days, traveled to General Washington’s encampment at Valley Forge. Henry Dearborn, a companion of Arnold’s at Quebec and Saratoga recorded Arnold’s arrival brought “great joy to the army.” Washington was thrilled to see his stalwart commander and anxious to get Arnold his next assignment. However, Arnold was still unable to ride a horse and it was clear Arnold would not participate in the 1778 campaign.

To reward Arnold, Washington appointed him to the prestigious position of military commander of the Philadelphia region in June. It was a sedentary post which did not require any field duty and one befitting a man of Arnold’s fame. However, it also required great tact and patience, two traits in which Arnold was greatly lacking.

Moreover, being one of the most powerful men in Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, was a situation ripe for abuse. Perhaps three years before, when Arnold was still the devoted Patriot, he could have withstood these temptations. Now, wounded both mentally and physically, it would prove to be too much for the man.

Next week, we will discuss the fall of Benedict Arnold. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, who commanded the unit that had captured the British spy Major John Andre, ordered an aide to take word to General Benedict Arnold about Major John Andre’s capture. He sent another aide to find and inform General George Washington as well.