Benedict Arnold’s Betrayal Begins

Benedict Arnold’s betrayal of the United States followed a series of disappointments and slights, both real and imagined. The final chapter in this sad story was the offer to hand over Fortress West Point to the British in September 1780, but the saga began in the Spring of 1779.

Arnold married the beautiful eighteen-year-old Peggy Shippen in April 1779 and shared with his teenage bride how time and again Congress had failed to properly reward Arnold’s efforts to help the country gain its independence. During their courtship, Peggy had seen her paramour repeatedly criticized, wrongfully in her eyes, and she came to stand by her man. Together, they hatched a plan to make money the old-fashioned way, by betrayal; in this case, by Arnold selling American military secrets to the British.

They sent John Stansbury, a Philadelphia merchant and double agent, to New York with a message for Major John Andre, the British spy chief, that Arnold was willing to provide useful information to the British for a price. Andre could hardly believe what he was told by Stansbury, but he immediately promised Arnold liberal compensation if he provided a steady stream of intelligence to the British.

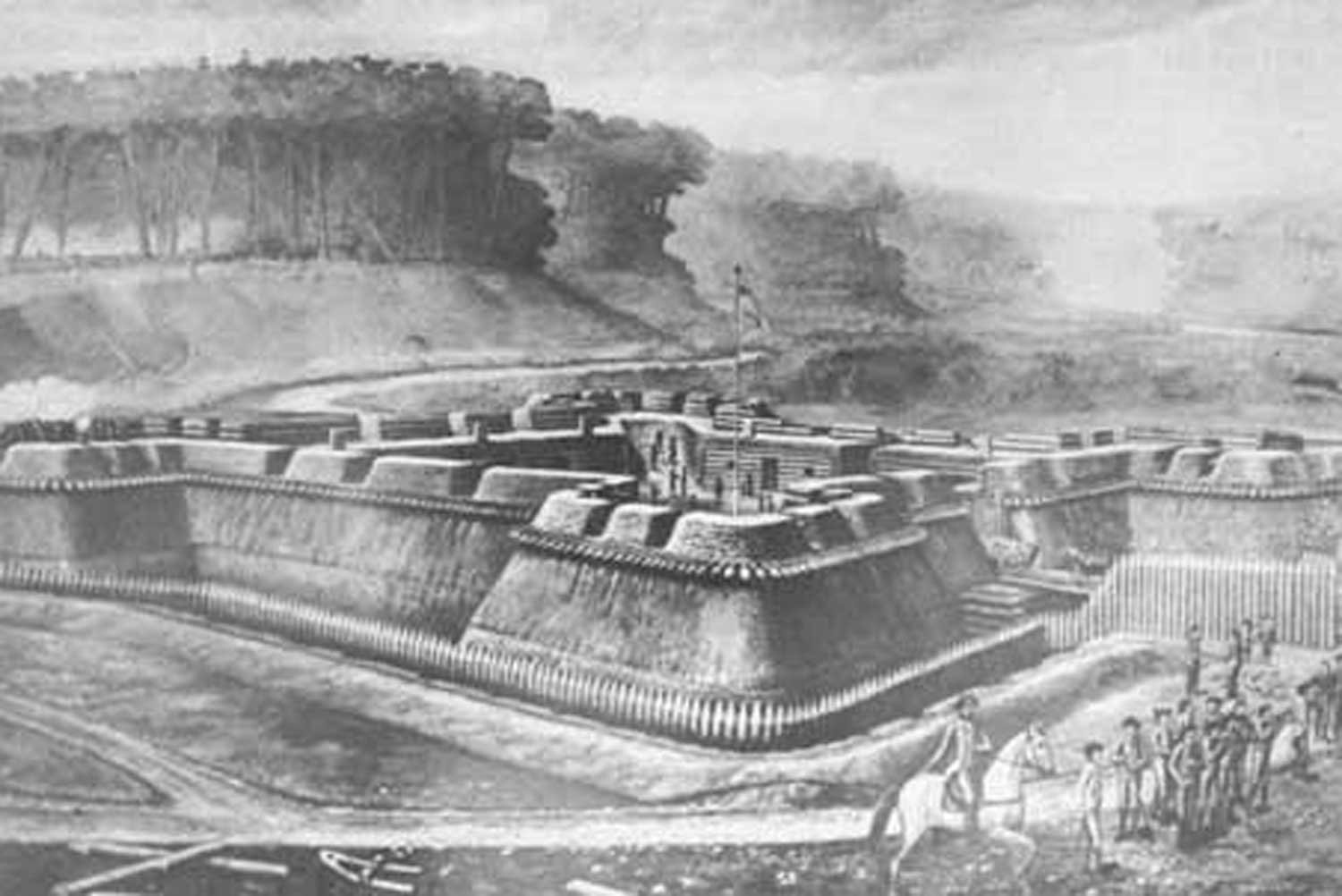

About this time, Sir Henry Clinton, the commander of British troops in North America, was developing plans to seize Fortress West Point, the key American bastion in the colonies. It was located on a point of land in the Hudson Highlands that jutted out into the Hudson River and from which river traffic could be controlled. It was arguably the most strategically important site in America and was well defended by General George Washington’s Continental Army.

About fifteen miles south of West Point, the British held a key post on the river called Stony Point. In one of the more daring moves of the American Revolution, on July 15-16, 1779, General Anthony Wayne attacked and captured the fort and about 500 prisoners in a late-night raid. Although Wayne quickly withdrew after his victory, much like Washington did at Trenton, Clinton was furious at this embarrassing loss. He was determined to drive Washington’s men from the Hudson River Valley, and seizing West Point was the key.

On May 21, Arnold sent his first encoded message to Andre, beginning a long string of coded correspondence. Amazingly, despite countless obstacles and the need to cross enemy lines with every letter, no message was ever captured, and their deceit was never detected.

Arnold began by sending troop strength reports for all colonial militias and the Continental Army to Sir Henry. Early on, Arnold let Clinton know that this was a business deal and he wanted a contract up front with a guarantee of ten thousand British pounds.

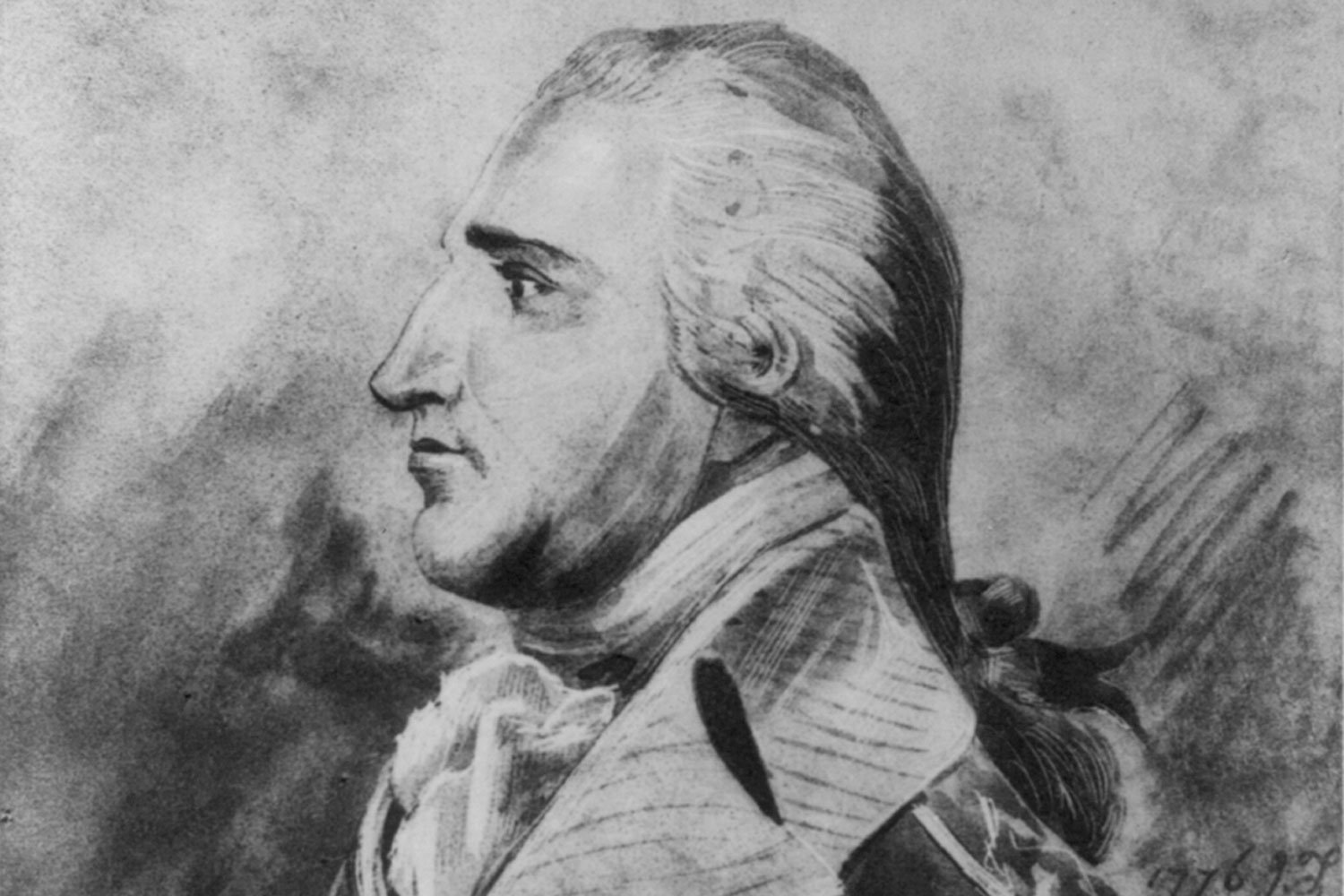

“Major Andre.” New York Public Library.

For his part, Clinton was skeptical of Arnold’s intentions and wanted concrete proof that Arnold could and would deliver substantial, not just general, information. What he wanted most were specific details on the defensive works around West Point and the units assigned to defend them.

Frustrated by the lack of progress and any financial compensation, Arnold began to lose interest in his deception and stopped corresponding with Clinton in the summer. Arnold was a man who pursued what he wanted with unrelenting vigor, so it is entirely possible he was also having second thoughts. After all, this devoted patriot had repeatedly risked his life in the American cause. Only Peggy kept the lines of communication open, staying in contact with Major Andre throughout the fall and assuring him that the idea was not dead.

Meanwhile, in January 1780, Arnold’s trial to address the charges brought against him by Joseph Reed, the powerful head of Pennsylvania’s Executive Council, was finally held. Arnold was exonerated of all charges but was found by the court to have used bad judgement in two instances. On January 27, the judges referred the matter to General Washington for him to officially reprimand his subordinate.

Arnold expected at most a slap on the wrist from his Commander with whom there was such mutual respect and admiration. To Arnold’s dismay, Washington’s general orders of April 6 contained a fairly harsh public reprimand of Arnold’s actions. While praising Arnold as a great patriot, Washington stated he was duty bound to criticize any breach of conduct or integrity.

In a private letter sent the same day, Washington tried to mend fences with his stalwart battlefield general. He reminded General Arnold that someone like him who was held in such high regard by his fellow citizens must be particularly careful in his conduct. Washington further stated he still had the utmost respect for Arnold and wanted to keep him in the Continental Army, but these kind words came too late.

In Arnold’s mind, the one man on whose support he could always count had turned against him. This disappointing reprimand may have been the straw that broke the camel’s back. Within weeks, Arnold renewed his correspondence with Clinton, informing him that Arnold expected soon to be named commander of West Point, the fort Clinton coveted most. This was a lie as General Washington had not promised Arnold anything, but Arnold planned to manipulate his way into the position.

Next week, we will discuss Benedict Arnold’s scheme going awry. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, who commanded the unit that had captured the British spy Major John Andre, ordered an aide to take word to General Benedict Arnold about Major John Andre’s capture. He sent another aide to find and inform General George Washington as well.