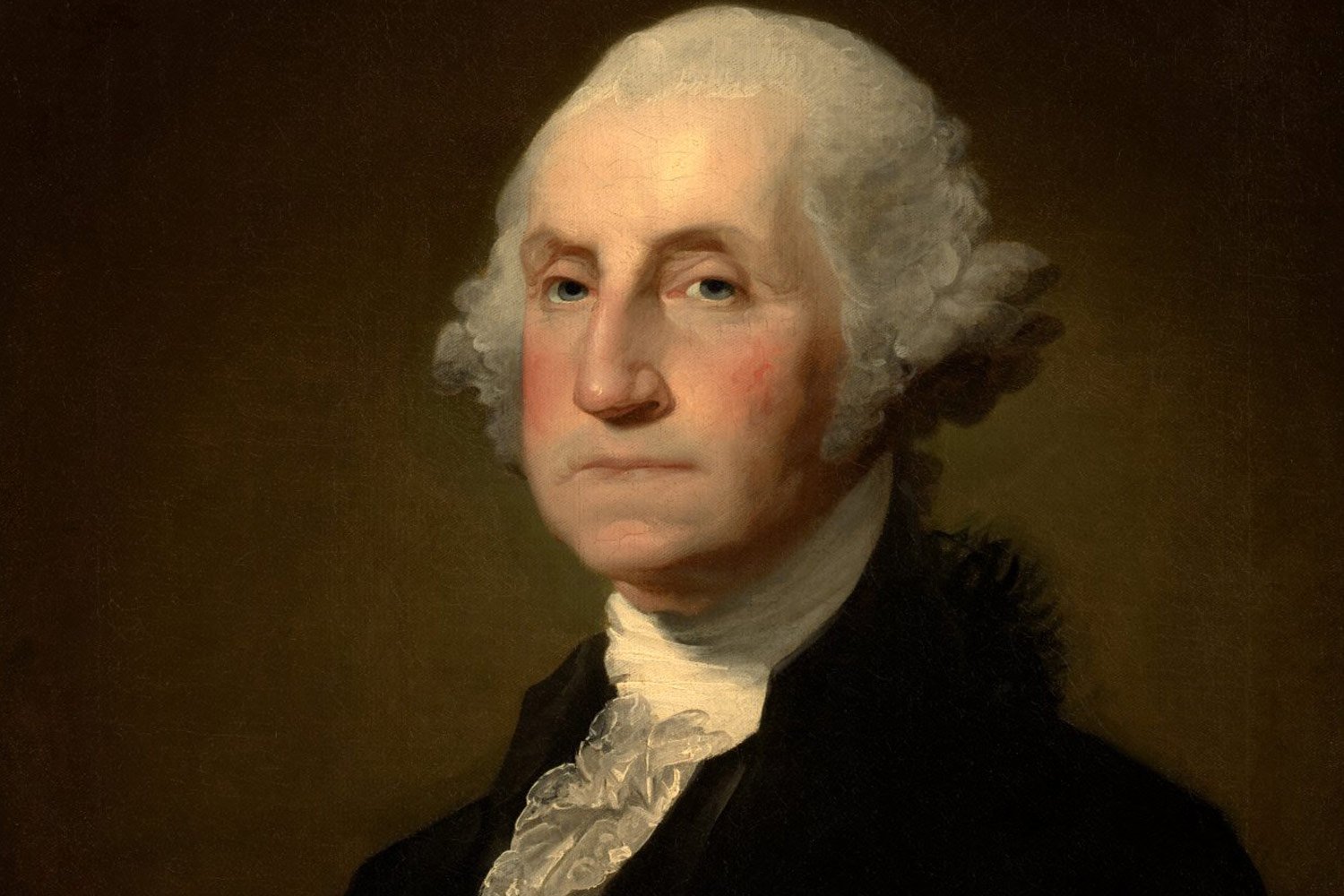

George Washington’s Formative Years

George Washington. Where do you begin to tell the story of this incredible man? A man to whom this great country of ours owes so much. Like most stories, it is best to start at the beginning where the foundation was laid for the man he would become.

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 at Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia. His father, Augustine Washington, was a justice of the peace who owned a fair amount of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia.

In 1735, Augustine moved his family to Little Hunting Creek and three years later to Ferry Farm near Fredericksburg. When Augustine died in 1743, George inherited Ferry Farm and his half-brother Lawrence inherited Little Hunting Creek which he subsequently named Mount Vernon.

Although Augustine had sent George’s two older half-brothers to England for a classical education, his unexpected death in 1743 prevented George from following in their footsteps. Consequently, George’s education came at the hands of private tutors and his own readings.

In addition to reading and writing, Washington studied Geometry and Trigonometry in preparation for his career in surveying and, interestingly, he also studied manners. Specifically, he copied out 110 “Rules for Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.” Its teachings clearly influenced the formation of Washington’s later character.

He also showed an early interest in former military leaders, studying ancient legends Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, as well as more contemporary heroes Charles XII of Sweden and Frederick the Great of Prussia. The lessons learned from these men proved valuable to Washington when facing difficulties in the American Revolution.

In any event, by age 15, Washington was finished with his formal schooling and began his first career as a surveyor. With the aid of his relative, Lord Fairfax, George was named surveyor for Culpepper County in 1749. His experiences in this capacity hardened and toughened his body and taught him to be self-reliant at a young age. It also piqued his interest in western lands, an interest he never lost.

In 1752, George’s half-brother Lawrence died after being stricken with tuberculosis and two months later Lawrence’s daughter also died. Thus, at age 20, George came into control of Mount Vernon, one of the finest estates in Virginia. (George would not own Mount Vernon outright until Lawrence’s widow passed away in 1761.)

About this time, things in North America were heating up between France and its Indian allies, and the British. Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor, Lord Dinwiddie, appointed Washington as a major in the militia and commander of one of the colonies four districts.

In 1753, when learning of a French outpost, Fort Duquesne, on the Ohio River near present-day Pittsburgh, Dinwiddie sent Washington there to deliver an ultimatum for the French to leave. Washington completed this arduous round trip in 77 days. Although the French refused to comply, Washington gained a degree of fame from this exploit.

The following year, Washington, recently promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, was dispatched to this same area, but this time with two companies of militiamen from the Virginia Regiment to force the French to leave. Arriving in the area, Washington learned a small party of French soldiers was nearby and he successfully attacked them on May 28th. This incident, known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen, began the French and Indian War.

In June, Washington was promoted to full Colonel and given command of the Virginia Regiment. However, on July 3, 1754, the full French force returned and administered a crushing defeat on Washington at Fort Necessity, forcing him to surrender. However, Washington’s star continued to rise despite this setback.

The following spring, General Edward Braddock arrived with a force of about 1,300 regular soldiers and marched back to Fort Duquesne with Washington along in an unofficial capacity. Despite outnumbering the French by 4 to 1, Braddock’s force was soundly defeated, and Braddock was killed. Washington, displaying tremendous courage (he had two horses shot out from under him and he had four bullet holes in his clothing but was not injured), rallied the troops and prevented a complete rout.

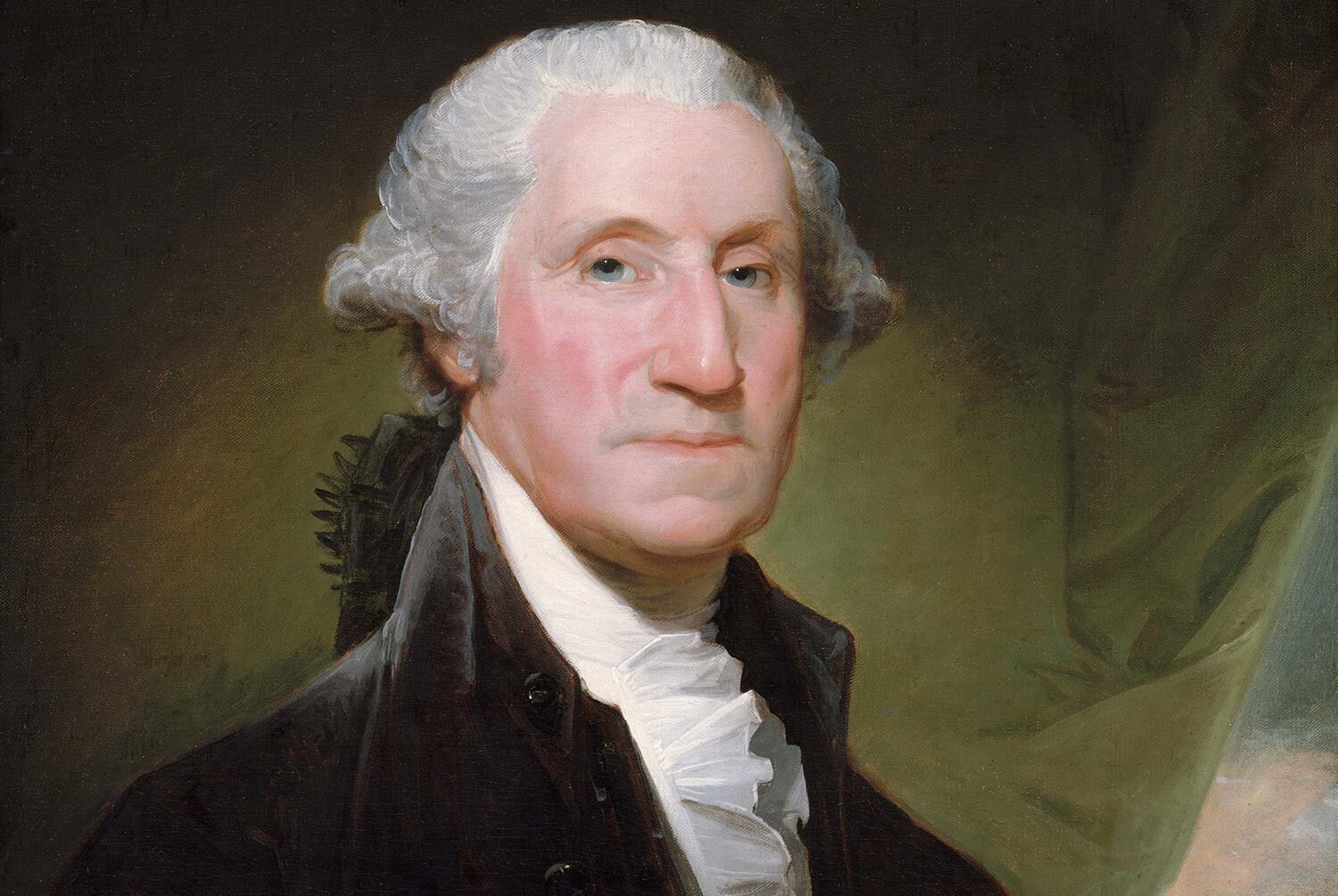

Although George Washington continued to command the Virginia Regiment with great success until 1758, this battle largely ended George Washington’s military career in the field until the onset of the American Revolution. Throughout this period, Washington displayed perseverance, coolness under fire, and courage that inspired those around him. These traits would manifest themselves again in Washington on a larger stage twenty years down the road.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why should George Washington’s early years and young manhood experiences matter to us today? The man George Washington was to become was largely created during his formative years. The time he spent as a surveyor and young militia officer hardened his body and taught him leadership lessons he could only have gained in the field.

Lacking the opportunity to obtain a formal education, Washington read a great deal and learned in the school of hard knocks. These experiences combined with his God-given abilities are what enabled him to become the Father of our Country. Therefore, to fully understand George Washington we need to study his youth.

SUGGESTED READING

Arguably, the most detailed book ever written on George Washington is the Pulitzer Prize winning seven-volume set, entitled George Washington, authored by Douglas Freeman in 1948. A superb one volume edition of Freeman’s masterpiece called Washington was published in 1968. It is highly recommended.

PLACES TO VISIT

Fort Necessity National Battlefield is in southwest Pennsylvania about 90 minutes from Pittsburgh. It is the site of Colonel George Washington’s surrender to the French in 1754. A restored fort is in a lovely setting and there is a nice visitors center with many outstanding exhibits.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.