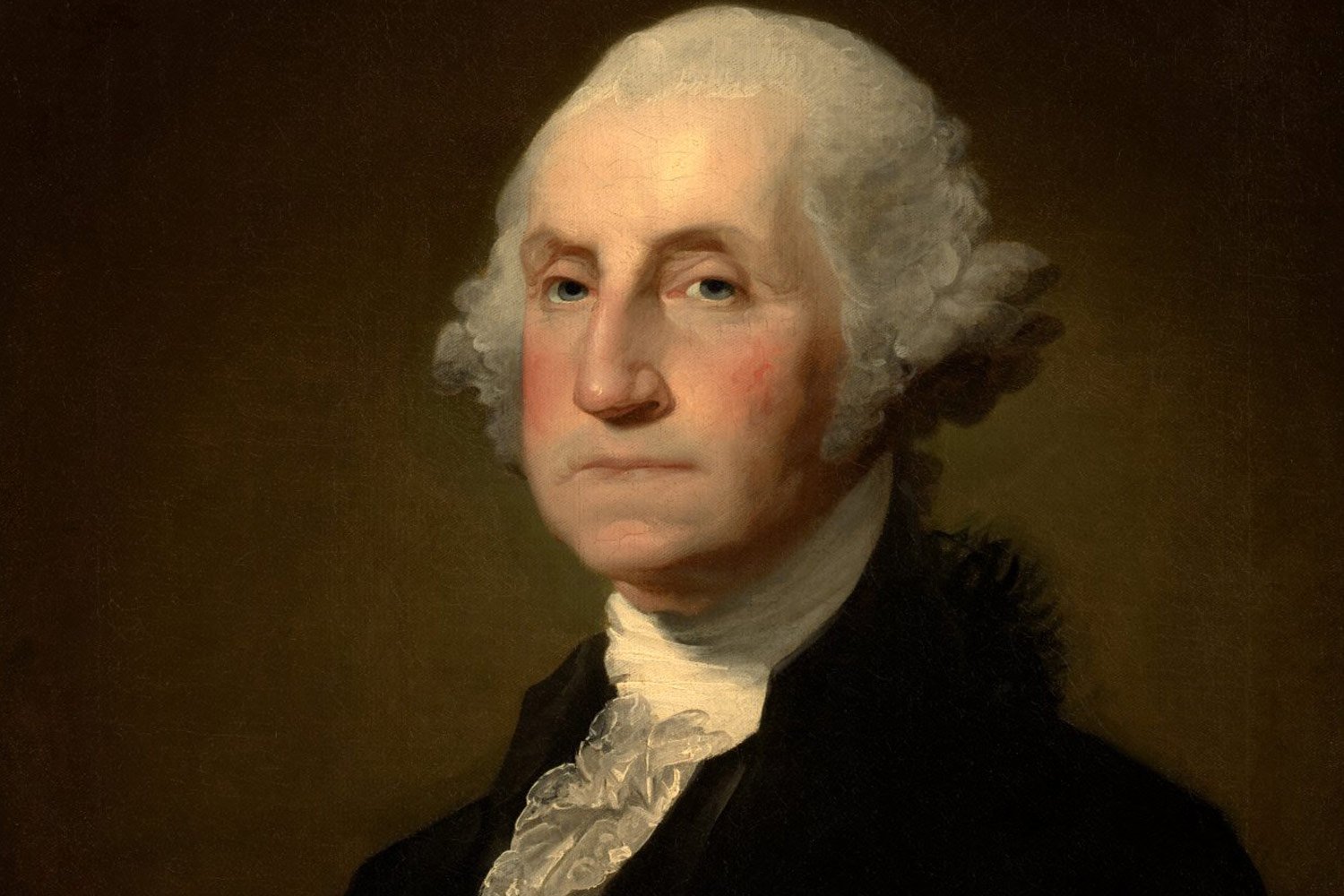

George Washington, Life as a Gentleman Planter

When George Washington resigned as Colonel and Commander of the Virginia Regiment in 1758, he returned to Mount Vernon to begin his life as a gentleman planter. Although in less than twenty years Washington would be called away by his country, his time between the French and Indian War and the American Revolution was a significant portion of this great man’s life.

Washington had hoped for a regular commission in the English army due to his successes in the field. While being commander of the Virginia Regiment was prestigious, real fame and the best career path was found by obtaining a regular army commission. Once his request was denied by British officials, he moved onto to the next phase of his life.

Soon after resigning his commission and returning home, George married Martha Dandridge Custis on January 6, 1759. Martha, a wealthy widow at the age of 26, and George had met the previous March when George called on Martha at her home. At the time, Martha had been widowed about a year and had two children, John “Jacky” and Martha “Patsy” (two others had died in childhood).

Although capable of managing her affairs, Martha wanted a companion and someone to help raise her children. George and Martha were a good match being about the same age, both wealthy landowners, and from the same social circle. Most importantly, they seemed to have genuine affection and respect for each other. While they never had any children together, George loved Martha’s as if they were his own.

After the marriage, the Washington’s had Martha’s 17,500-acre estate and Mount Vernon’s 8,000 acres to manage. George attacked this task with his typical zeal and energy. He rose early every morning and worked the land six days a week, leaving Sunday for church, entertaining friends, conducting business deals, and drafting letters.

Not surprisingly, Washington was a successful and innovative farmer. He experimented with cattle breeding, cultivated numerous fruit orchards, and practiced crop rotation. When tobacco proved too difficult to sustain as a cash crop, he moved to planting wheat. As he consistently showed in his military career, George Washington was able to adapt to changing circumstances and persevere.

One of Washington’s central tenets in running his estate was to make his properties self-sufficient. To this end, George built his own water-powered flour mill, blacksmith shop, and distillery. Washington also set up a fishery adjacent to the Potomac and used the catches as one of their sources of food.

Additionally, Mount Vernon had its own set of carpenters, coopers (barrel makers), and shoemakers to service the needs of his family and the hundred or so slaves who worked on his plantations. By all accounts, Washington was a very humane master over his slaves. Although Washington did not free his slaves while he was alive, he granted them their freedom by a decree in his will. Moreover, he did not like the institution of slavery and advocated abolition.

As befitting a wealthy landowner in colonial Virginia, Washington became active in the colony’s politics. He first ran for a seat in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1755 but lost the election. Interestingly, it was the only political race he ever lost. He tried again in 1758 and this time was victorious. He also successfully stood for reelection in 1761.

Washington was a moderate during his time in the legislature and took a measured but critical approach of English policies such as the Stamp Act in 1765 and the Townshend Act in 1767. While calling Parliament “our lordly masters” and saying they “will be satisfied with nothing less than the deprivation of American freedom,” he also believed we should not be rash.

In a 1769 letter to George Mason, Washington stated, “something should be done to…maintain the liberty which we have derived from our Ancestors”, but that armed resistance “should be the last resource.” Characteristically, Washington was initially cautious in his approach to dealing with the approaching crisis.

However, after several attempts by the colonies to get England to modify their antagonistic stance, Washington became more radical in his thinking. At a meeting in August 1774, Washington declared he would “raise one thousand men, subsist them at my own expense, and march myself at their head for the relief of Boston.”

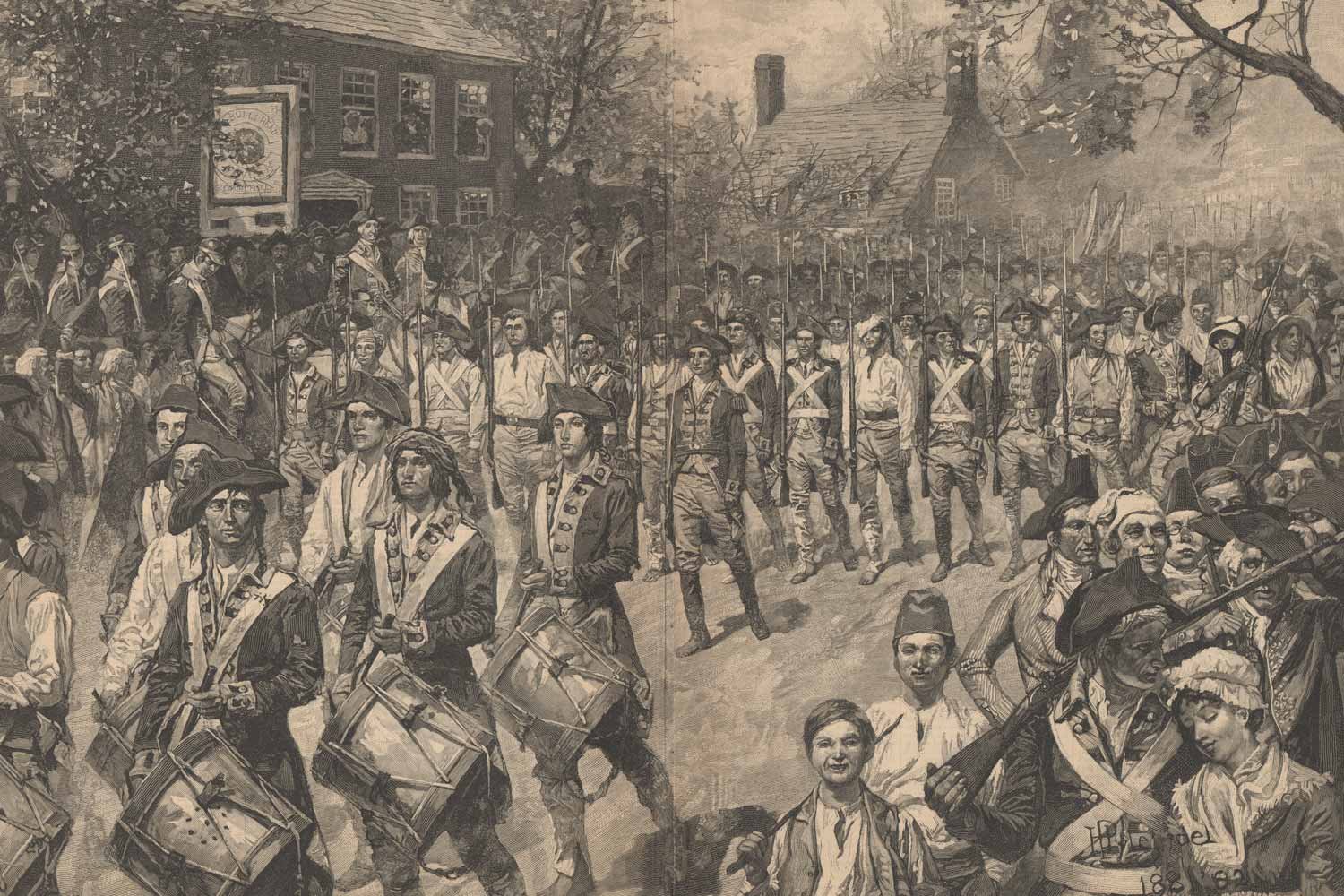

Shortly thereafter, Washington was selected by Virginia as one of its delegates to the first Continental Congress which met in Philadelphia in September 1774. Significantly, he attended that meeting in his full military uniform.

The next year he was selected by his home state to represent it at the second Continental Congress. It was at this conference, in June 1775, where the colonies first turned to George Washington to lead them to independence by offering him command of the Continental Army. The Age of Washington had begun.

WHY IT MATTERS

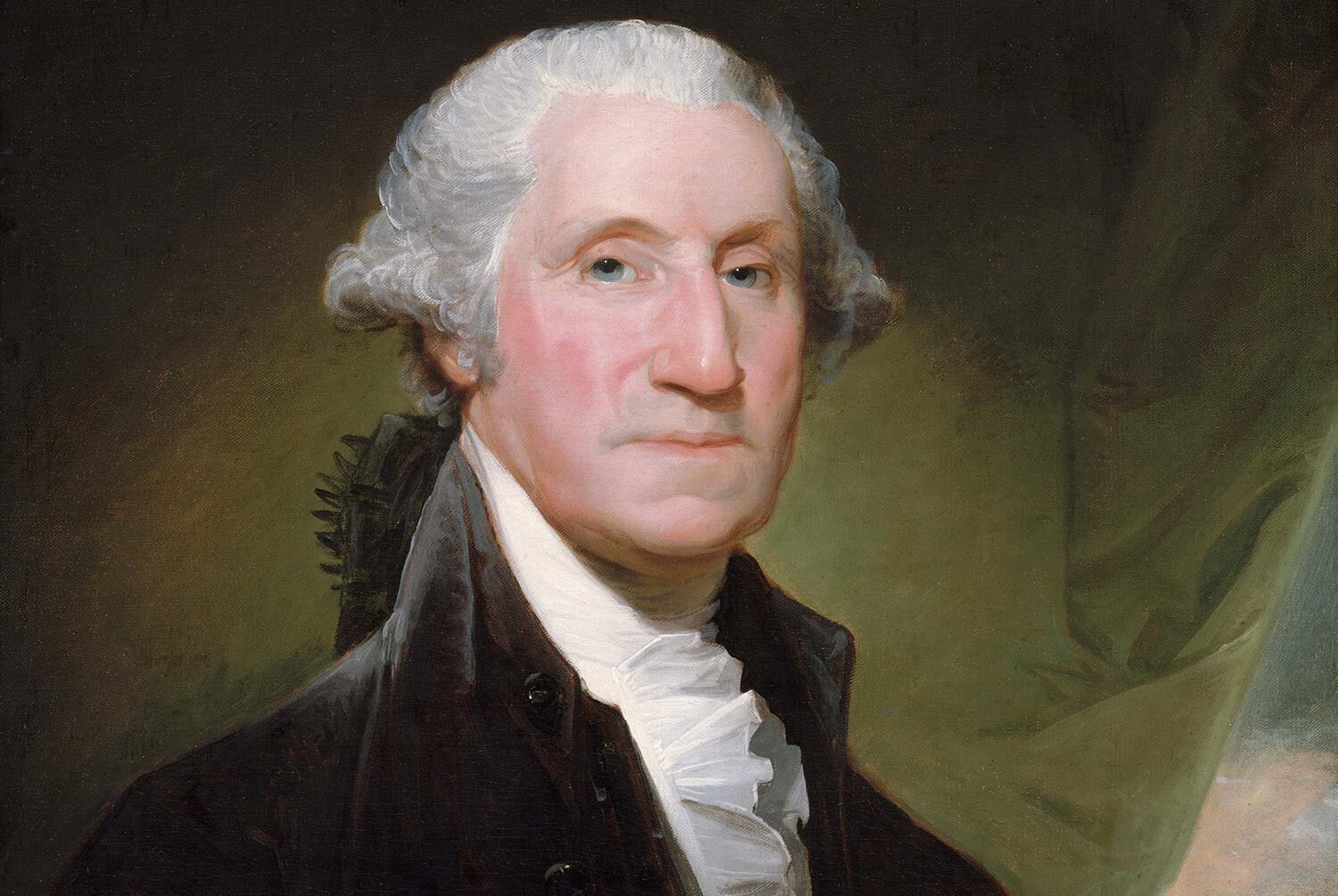

So why should George Washington’s experiences leading up to the American Revolution matter to us today? George Washington is such an iconic figure that we sometimes forget that he was first and foremost a citizen of America with many of the same challenges that befall us all. He had a home and family that meant a great deal to him and did not want to leave their side. The fact he gave up so much of this pleasant domestic life to serve his country makes his sacrifices even more noble.

Moreover, George Washington showed that his greatest qualities such as perseverance, hard work, and common decency which served him so well in war and as President also served him well in the less-lofty, day-to-day pursuits of life. The way he conducted himself in everyday life provides an example for all of us to follow. We are indebted to him for that gift.

SUGGESTED READING

An excellent book focusing on George Washington’s early life is Washington’s Revolution by Robert Middlekauff. Published in 2015, the book examines Washington’s experiences as a young man and commander of the Continental Army. It is well done and a good read.

PLACES TO VISIT

Mount Vernon is a must see for all Americans. Located on the Potomac River about 20 miles from Washington, DC, the house is beautifully restored, and the grounds are immaculate. The estate also has numerous completely restored buildings, including Washington’s profitable whiskey operation.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.