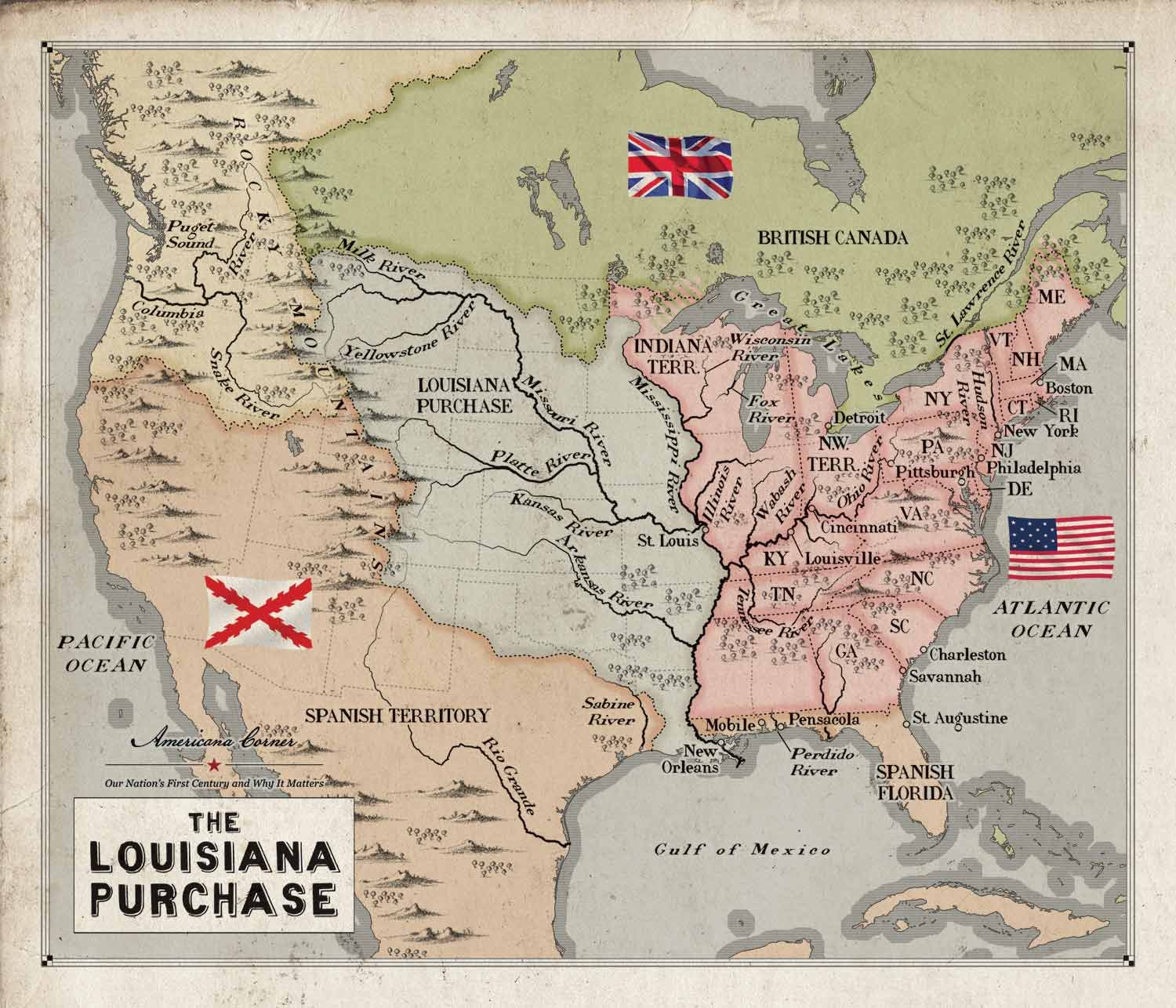

Louisiana Purchase

To download or save to print, click on a map to enlarge, right-click or control-click on the map, and select ‘save as’ or ‘save image as.’ Once saved, select ‘portrait’ orientation and print.

The midnight deal Robert Livingston, United States Minister to France, struck with Francois Barbe-Marbois, Napoleon’s Finance Minister, on April 13, 1803, to purchase the Louisiana territory was one of the most impactful agreements in the history of the United States. It resulted from months of conversations Livingston had had with numerous French officials, creating a foundation for the details that would follow. But as important as this step was, there remained several hurdles to overcome.

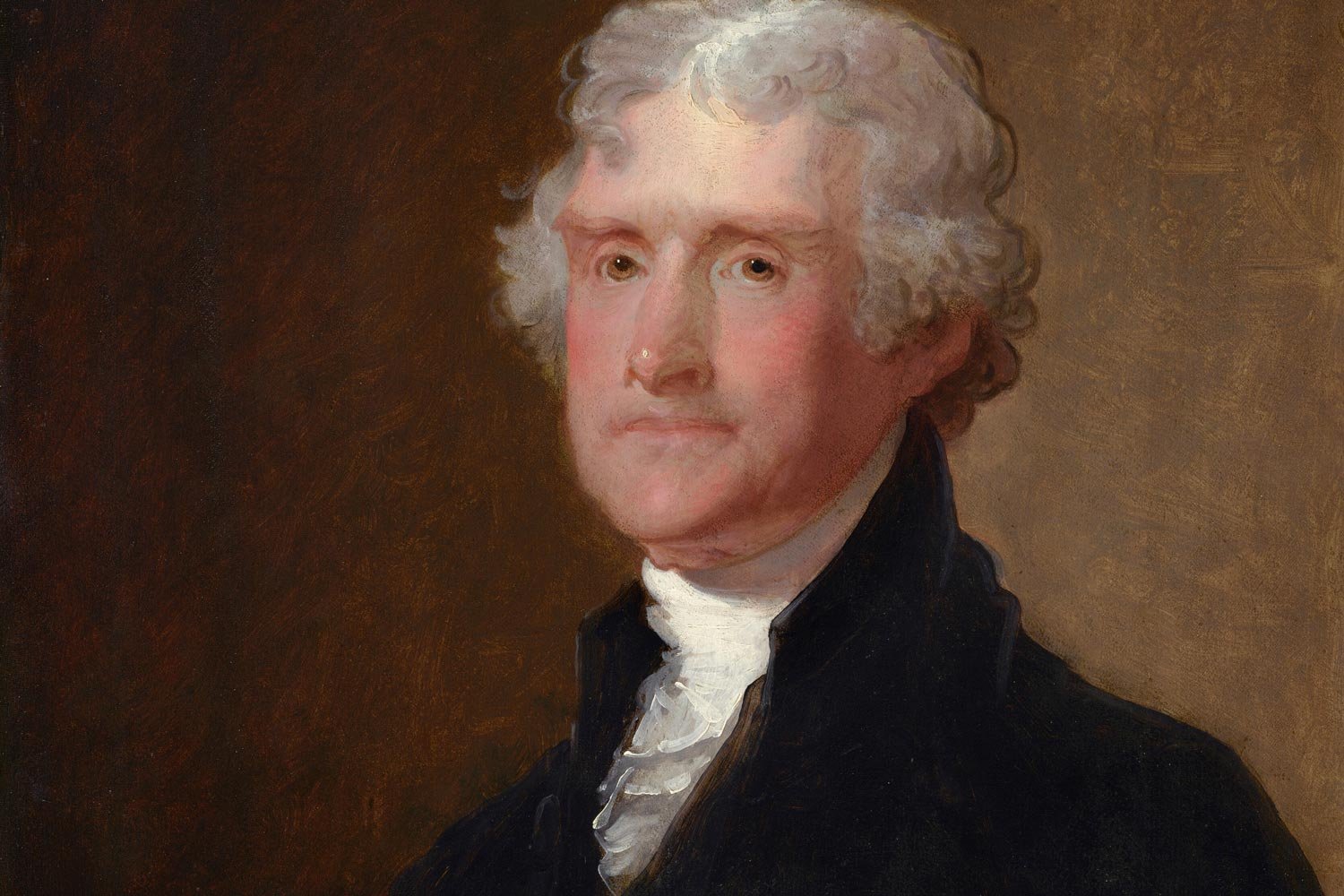

As a boy growing up in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson listened to his father tell captivating stories of the pristine wilderness beyond the Appalachian Mountains and dreamed of what opportunities lay in the uncharted lands of North America. As Jefferson grew to manhood, he became a proponent of national expansionism, recognizing that the future greatness of the country lay outside the original thirteen colonies.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 which officially ended the American Revolution was generous to the United States, much more so than most had expected. Besides recognizing American independence, the provisions which Great Britain proposed greatly expanded the boundaries of the new nation, granting the United States all the land north of the Ohio River as far west as the Mississippi and as far north as British Canada. But like all gifts from adversaries, this one came with some issues that would simmer for decades.

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 was one of the truly watershed events in American history. The acquisition of this vast land placed the United States firmly on a path towards both the domination of North America and the status of an emerging world power.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the first internal tax on the American colonies, and thus began a decade of missteps by the British. Their miscalculations would take their country and their colonists on a direct path to Lexington Green and Concord Bridge on April 19, 1775. During this same year, Thomas Jefferson was concluding his time studying law under George Wythe and began to turn his eye towards the world at large and, more specifically, politics in the Colony of Virginia.

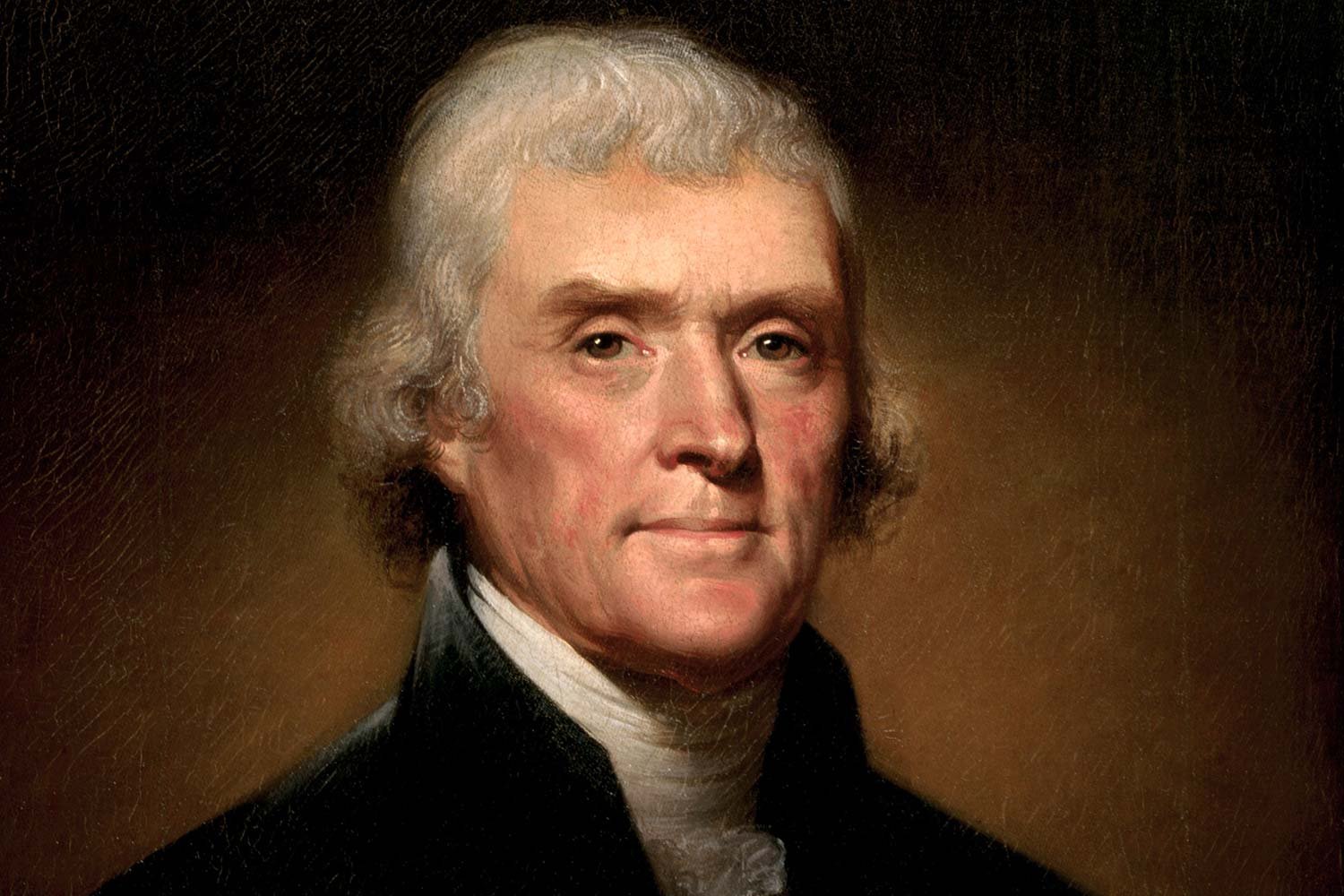

Thomas Jefferson is one of America’s most iconic Founding Fathers. Best known for his inspirational words in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was a brilliant man with diverse interests who spent the bulk of his life in service to his country and his later years in retirement at his beloved mountain home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia.

The presidential election of 1800 ended in a tie, as the two Democratic-Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, each received 73 electoral votes under the original guidelines of the Constitution.

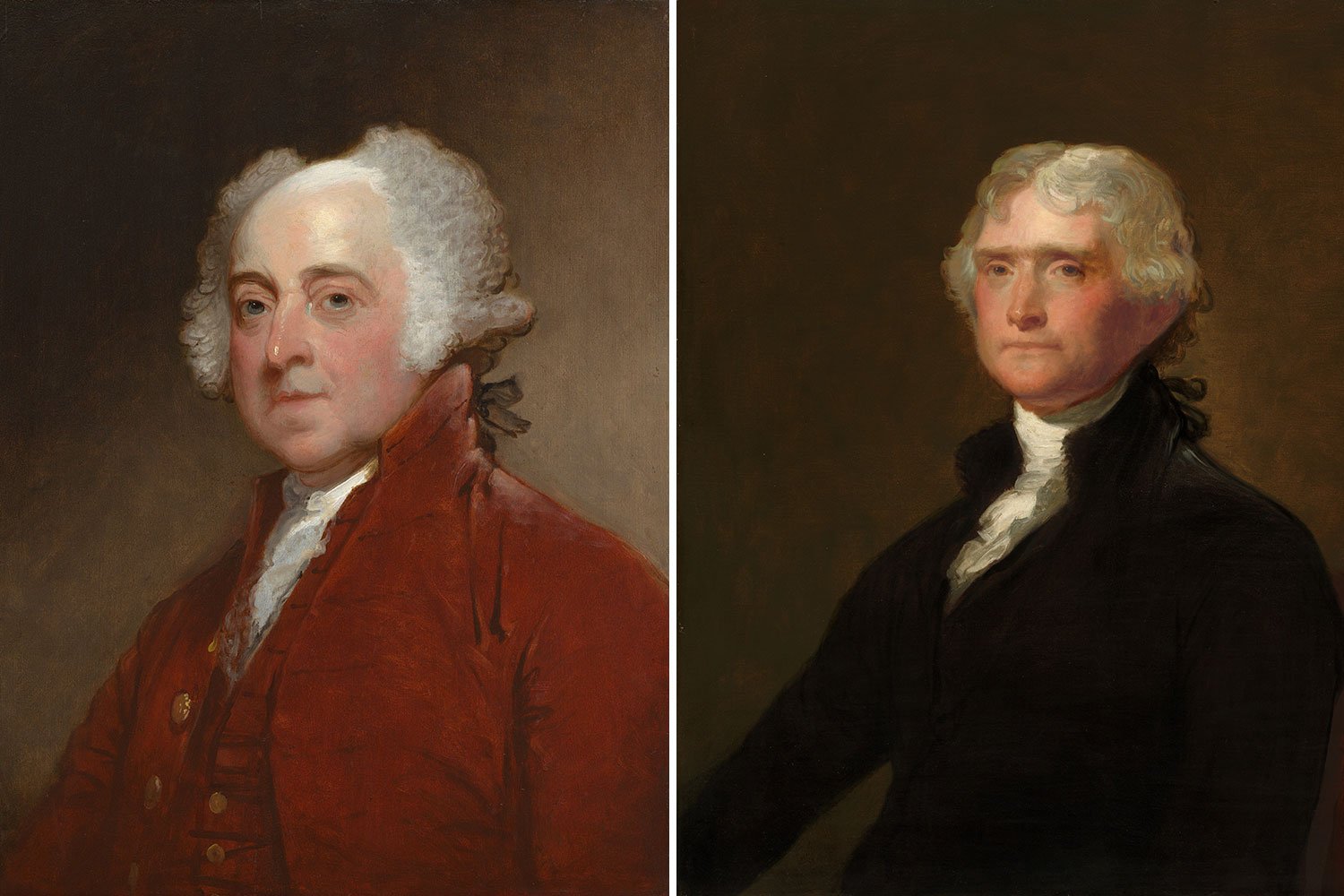

The Presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.

John Adams’s loss to Thomas Jefferson in the presidential election of 1800 was a great disappointment for Adams as he felt he deserved another term based on his accomplishments during his four years as President. But Adams accepted the verdict of the Electoral College and looked forward to the next phase of his life.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.

Between 1798 and 1800, the United States fought an undeclared war with France called the Quasi-War, or Half War, because it was not formally recognized by Congress. It was largely a naval conflict fought in the Caribbean and southern coast of America and developed because of a series of related events that soured the formerly strong relationship between the two nations.

America’s first armed conflict with a foreign nation following the American Revolution was not the War of 1812, but rather a mostly forgotten fight called the Quasi-War. Although little known today, in its time it made a significant impact on the course of American history, affecting trade, the creation of the United States Navy, and a presidential election.

In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts passed by the Federalist controlled Congress and signed by President John Adams in July 1798, Democratic-Republicans howled long and loud about the legislation that they viewed as an assault on both their party and the Constitution. They turned to their leader, Vice President Thomas Jefferson, to counter these Acts and, if possible, use them to their political advantage.

The disrespect shown to the United States by France in the XYZ Affair in the spring of 1798 pushed the Federalists who controlled Congress to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, a series of four laws, which President John Adams reluctantly signed into law in July. Posterity has viewed these measures harshly, but it is important to view them from the lens of 1798 and not modern times. At the time of their enactment, although many had reservations, the rationale behind them was not entirely groundless.

On March 4, 1797, John Adams was sworn in as the second president of the United States and began a four-year stretch that would be dominated by a deteriorating relationship with France. Adams would also see a decrease in support from his own Federalist Party as the supremely conscientious Adams pursued policies that he deemed best for the country, but not necessarily best for the party or his popularity.

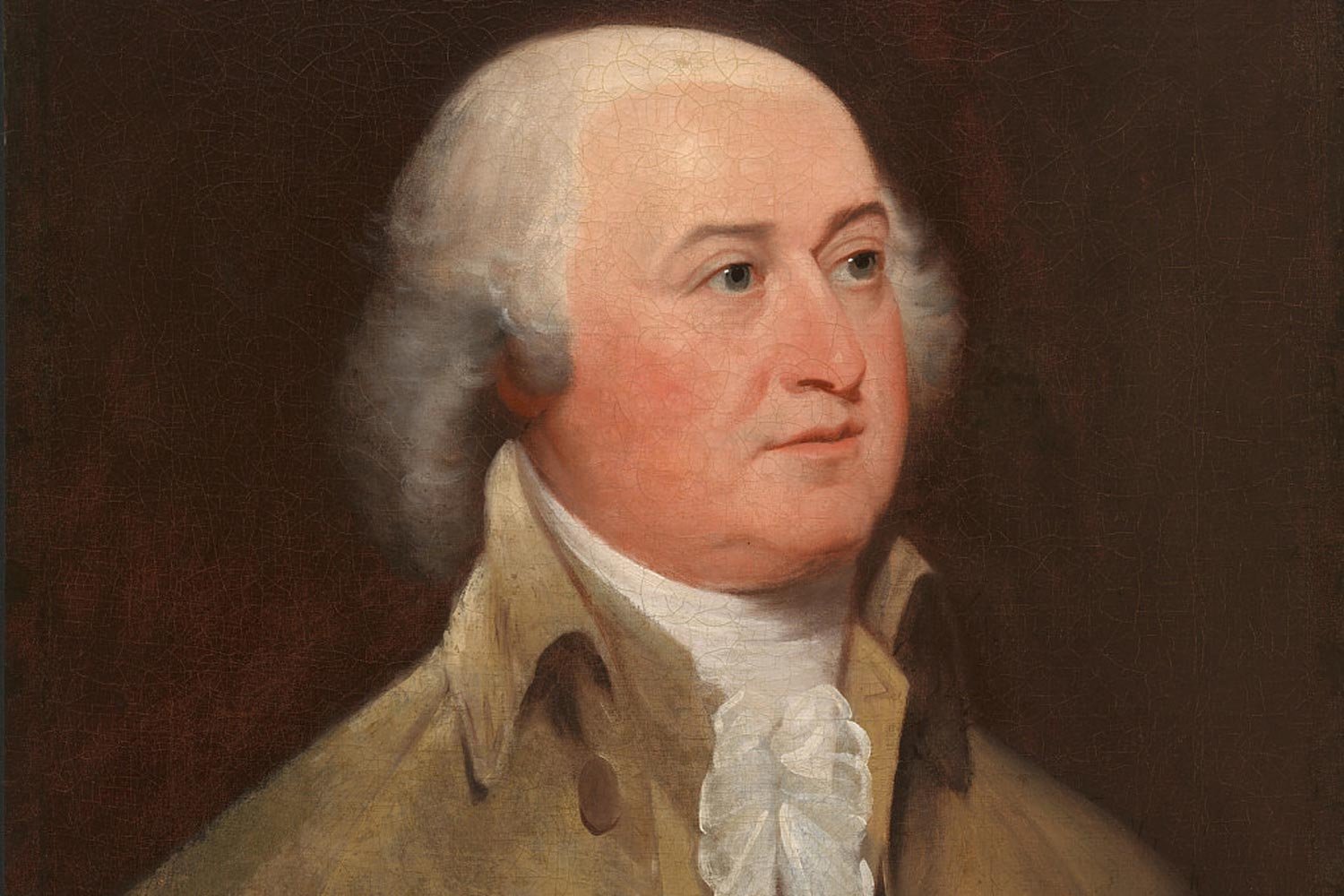

John Adams was one of America’s greatest patriots from the Founding generation. From gaining unanimous agreement from state delegations to the Declaration of Independence to obtaining favorable terms in the Treaty of Paris, Adams may have contributed more to America gaining her independence than anyone other than George Washington.

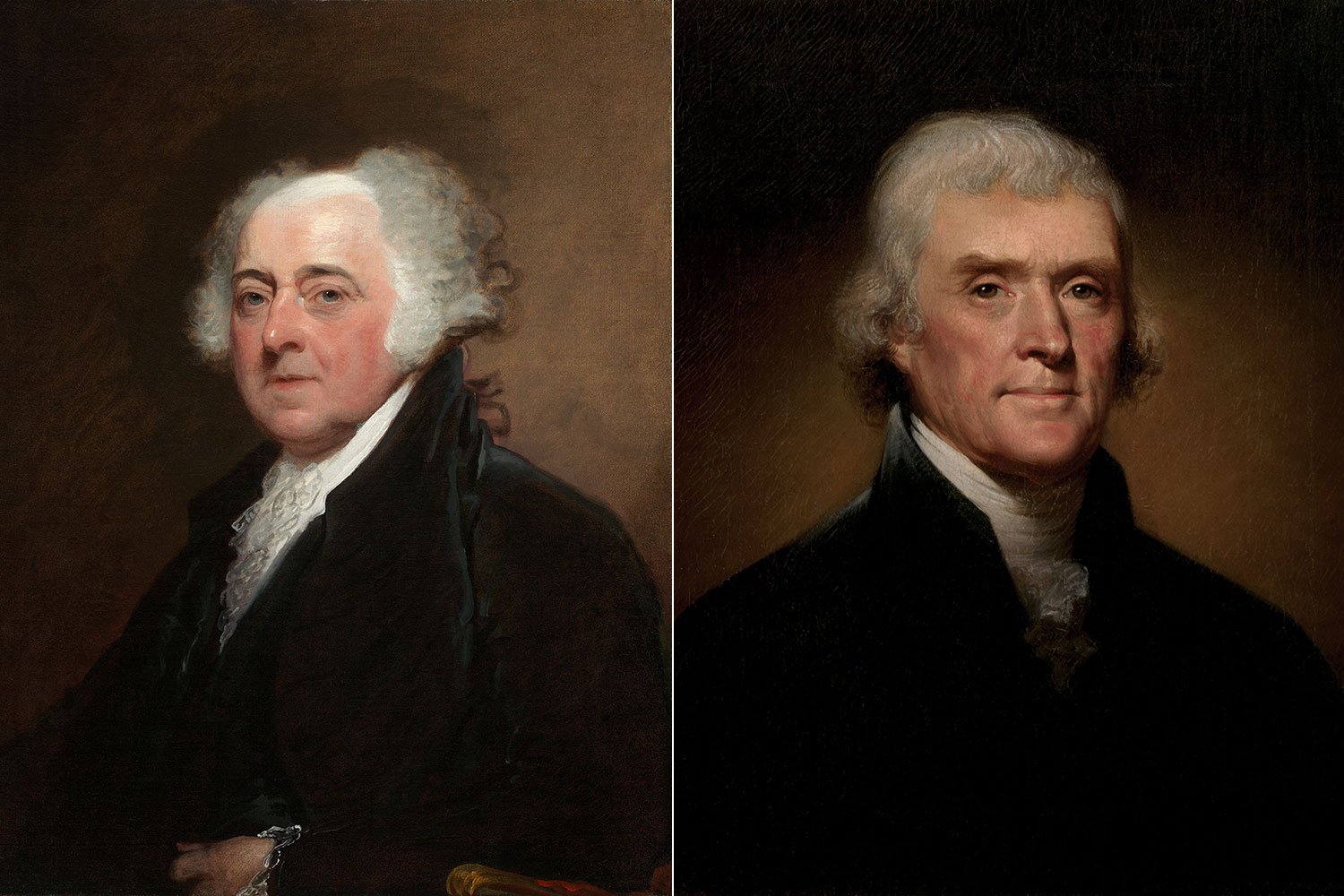

After serving two terms as President, George Washington decided to not seek a third and instead retire from public life. His decision led to the country’s first contested presidential election in the fall of 1796, pitting Thomas Jefferson against Vice President John Adams. Arguably, no presidential election in the history of the United States has ever featured a choice between two such American titans.

The dream of finding an all water route across North America, the mythical Northwest Passage, had been imagined since the time of Christopher Columbus. Incredibly, three hundred years after the Admiral of the Ocean Seas completed his epic voyages, the vast interior of the continent was still essentially unknown to Europeans. This great uncertainty led to numerous theories about what lay beyond what men could see.