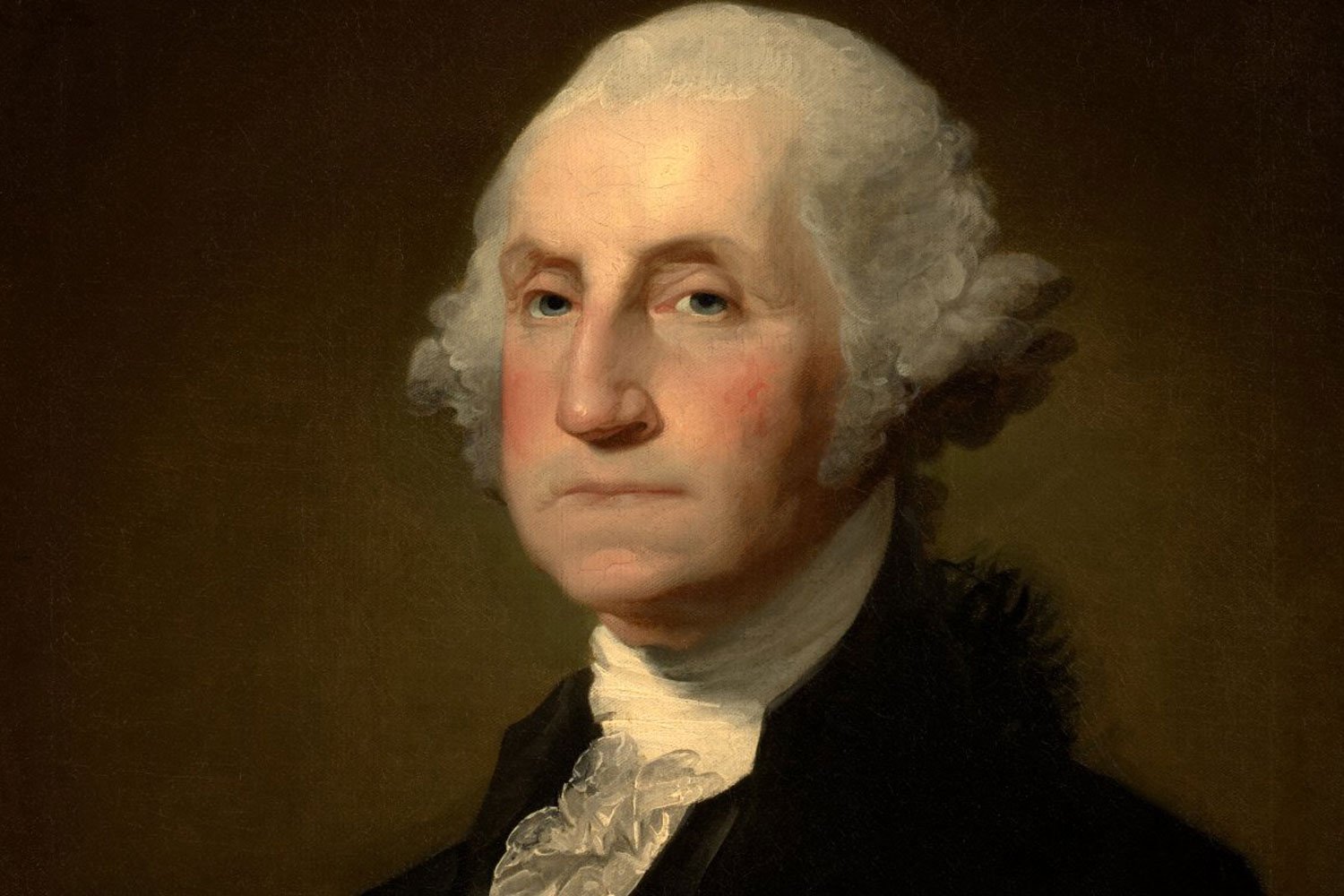

George Washington, Part One: Defining the Role of President

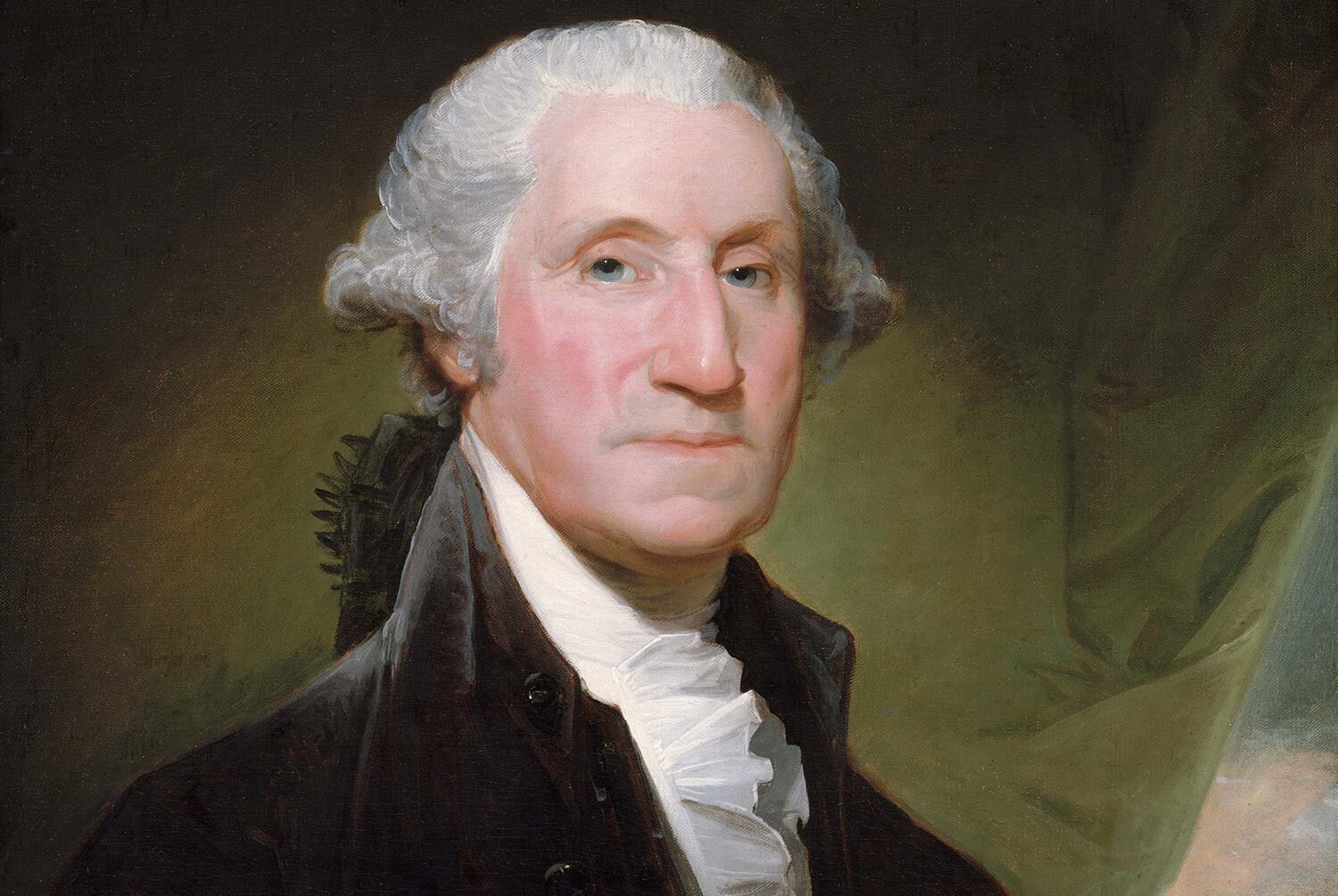

When the United States Constitution was created, one innovation was a more powerful executive. Everyone knew there was only one man conscientious enough to be entrusted with the job – George Washington. However, there was no guide to follow and no predecessor to lean on.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses how George Washington defined the role of president for others to follow, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of the National Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian Institution, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, National Guard Bureau, Library Company of Philadelphia, Wikipedia.

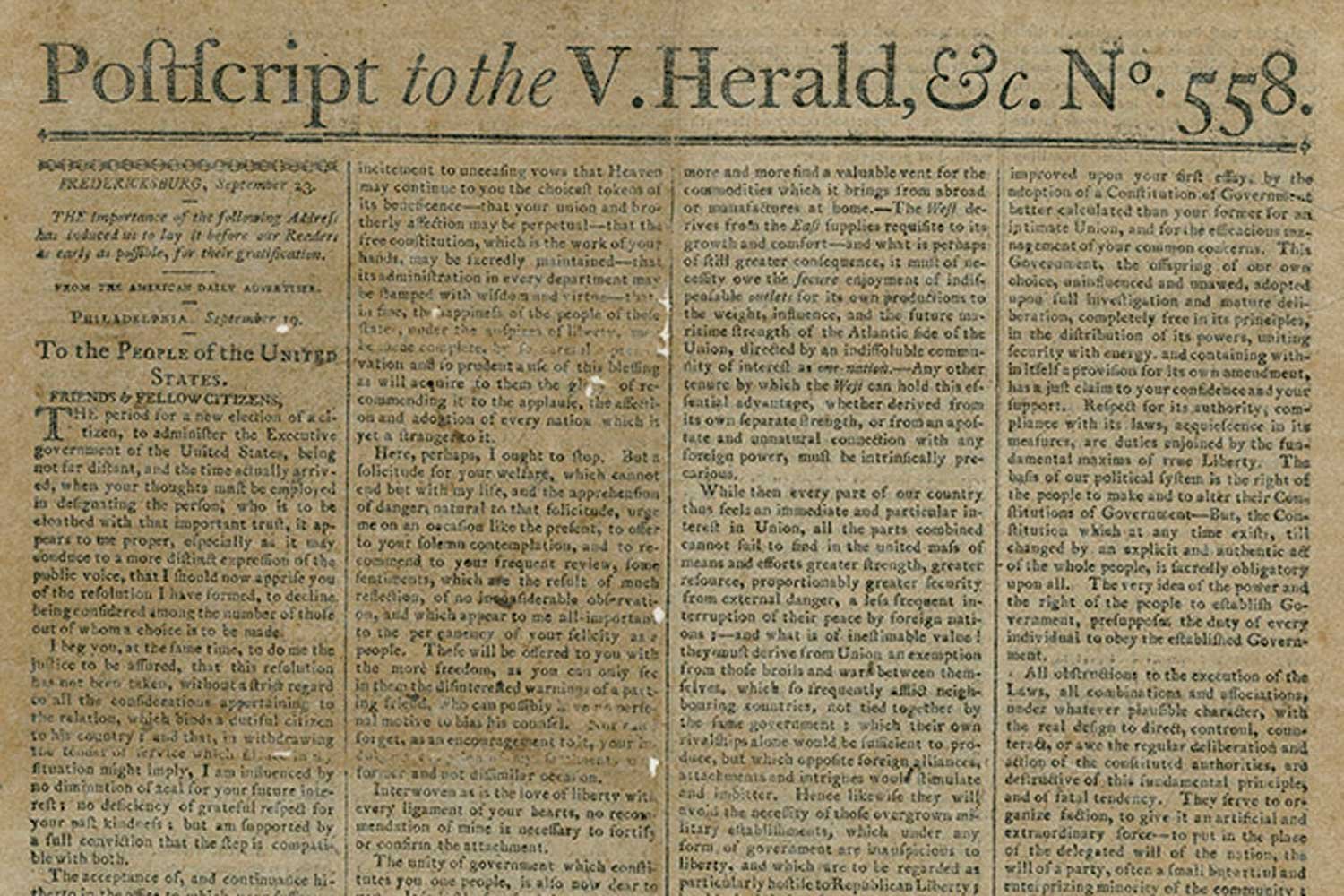

In his Farewell Address, President Washington shared his thoughts on several topics, including the need for America to remain fiscally prudent and to avoid permanent foreign alliances that could pull America into a costly war. With the fighting raging again in Europe, this time thanks to Revolutionary France, and with much sentiment favoring the French, Washington felt it necessary to advise a neutral course for the United States.

In May 1796, President George Washington asked Alexander Hamilton, arguably his most devoted and trusted assistant, to draft a letter informing the country of his intention of retiring from public life and explaining Washington’s reasons for doing so. This American masterpiece was crafted and word smithed by Hamilton, but all the ideas were Washington’s.

George Washington’s Farewell Address is one of the greatest documents in our nation’s history. It was a letter written by President Washington to his fellow citizens as he neared the end of his second term as President. Published in the American Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1796, its purpose was to inform Washington’s countrymen that he would not seek a third term as chief executive and provide the reasons why, as well as give some fatherly advice for America moving forward.

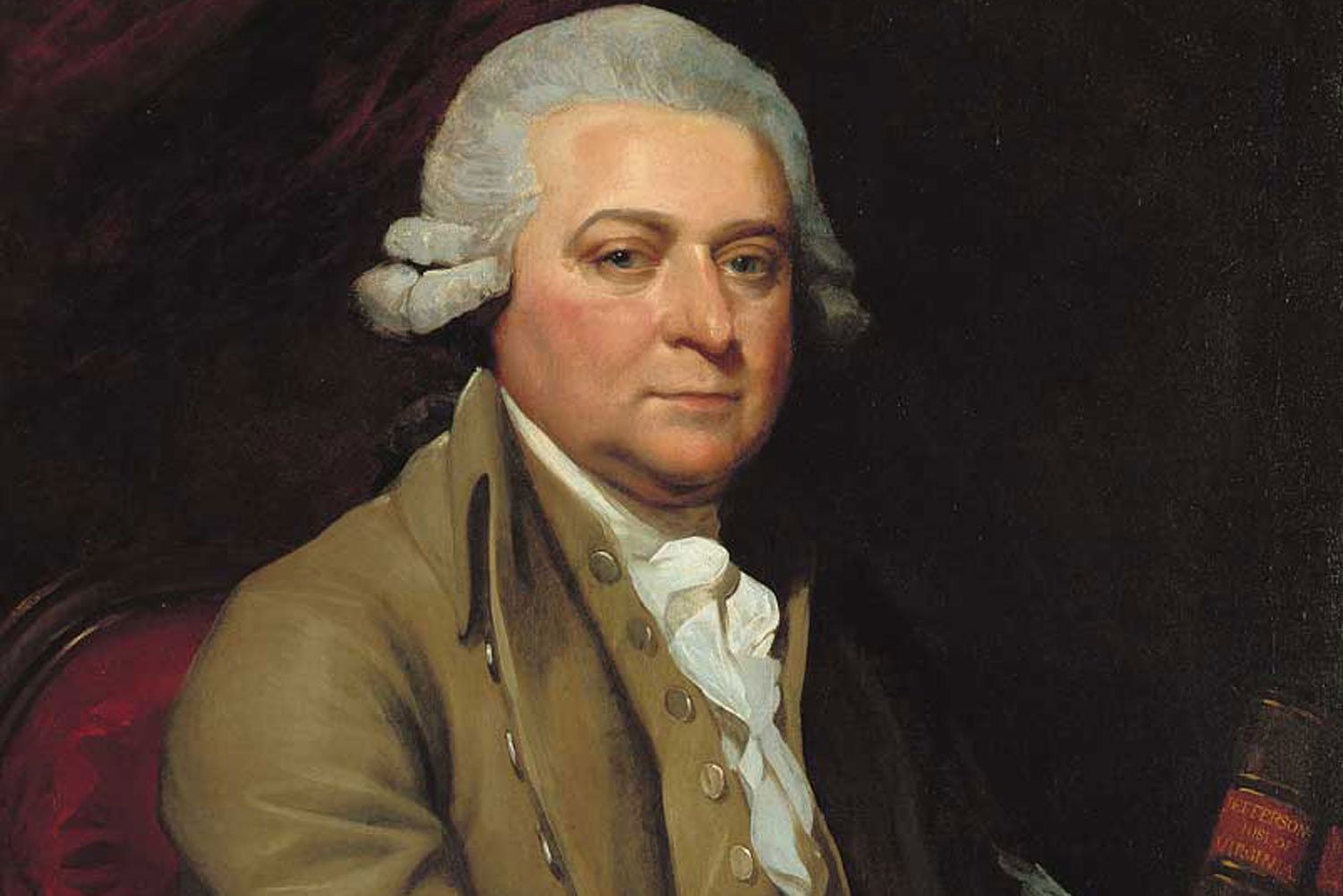

George Washington was again unanimously elected President in 1792 and sworn in on March 4, 1793. Although he had not wanted a second term, many, including Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison, felt the nation would suffer without his leadership. Reluctantly, Washington agreed to another four years.

The federal Constitution, the new law of the land, took effect on March 4, 1789, and had several notable differences with the Articles of Confederation. One of the most significant changes was the creation of a strong executive or President. However, the powerful executive reminded skeptics of the authority held by King George, and they worried the United States could eventually drift towards despotism. Virtually everyone knew that the only man strong enough to lead the nation and conscientious enough to be entrusted with so much power was George Washington.

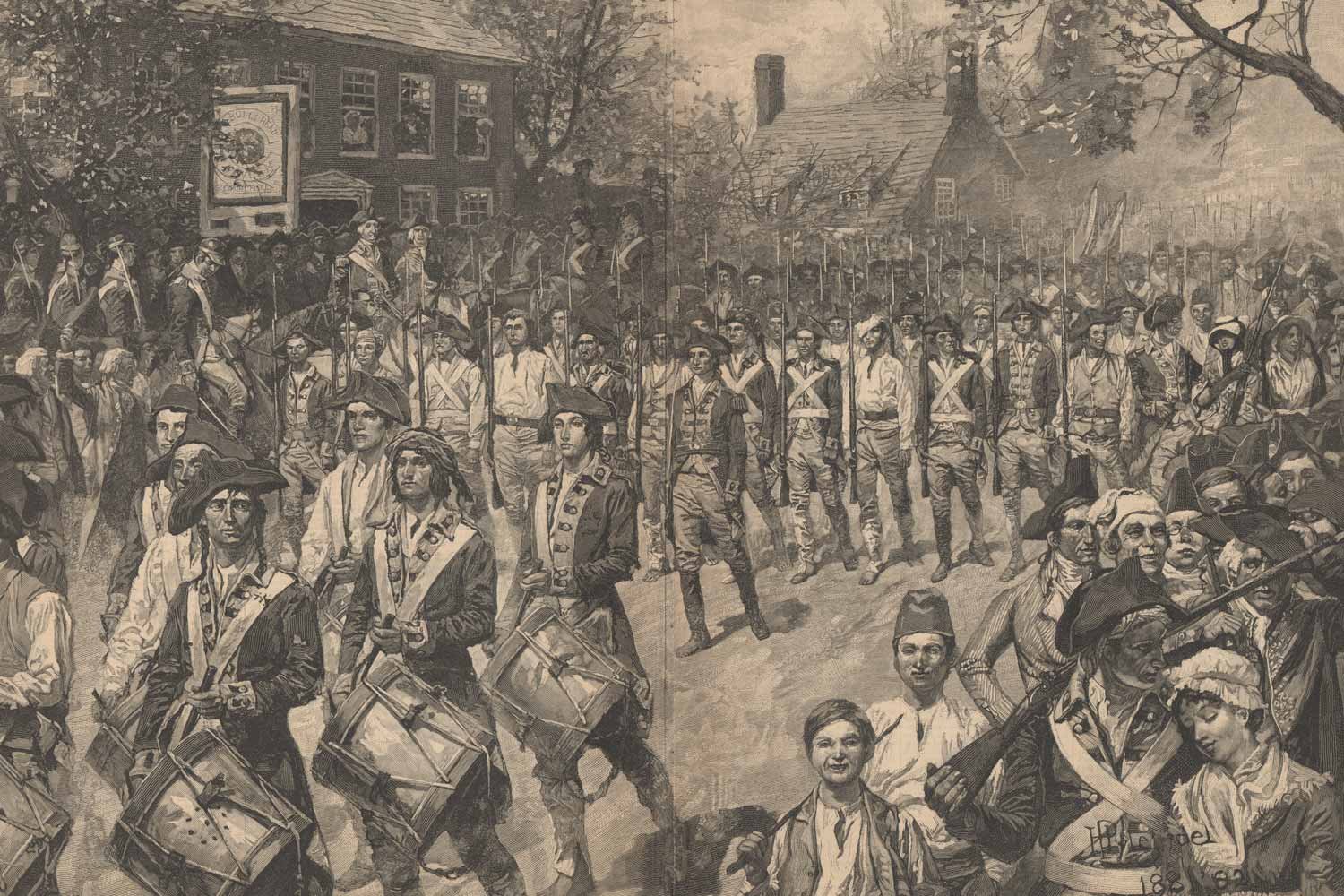

Following the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, the need to retain the Continental Army was diminished. With Congress financially broke and little reason to think that situation would change given they had no authority to tax, they decided to cut their costs and dissolved the army.

The Newburgh Conspiracy represents a time when our nation came closest to deviating from our core revolutionary principles of representative government with civilian control of the military. Because of a weak Confederation Congress and unhappiness within the officer ranks of the Continental Army, the stage was set for our new nation to drift into a military dictatorship or monarchy.

By early 1783, America was close to finalizing its peace agreement with England. However, the Confederation Congress had some issues to resolve with its own discontented Continental Army, as the internal threat of mutiny appeared worse than the external one posed by British forces.

We take civilian control of the military for granted today in America. However, were it not for General George Washington’s actions and words in the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy, things might be quite a bit different.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.

Our nation’s capital has twice been captured by a foreign army and in both cases, it was by British Redcoats. The more famous incident was the burning of Washington on August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812. However, the first occurred 37 years before that event, in 1777, when the British captured Philadelphia, the capital of newly independent United States.

General George Washington and his Continentals had achieved a great victory at Trenton on December 26, but the General saw another opportunity if he acted aggressively. On December 30, he recrossed the Delaware hoping for another miracle.

In late December 1776, the American Revolution had reached its low point. The 16,000-man Continental Army that had driven the British out of Boston in March 1776, had lost countless battles over the course of nine months and dwindled to a skeletal force of 3,000 soldiers on the west side of the Delaware River.

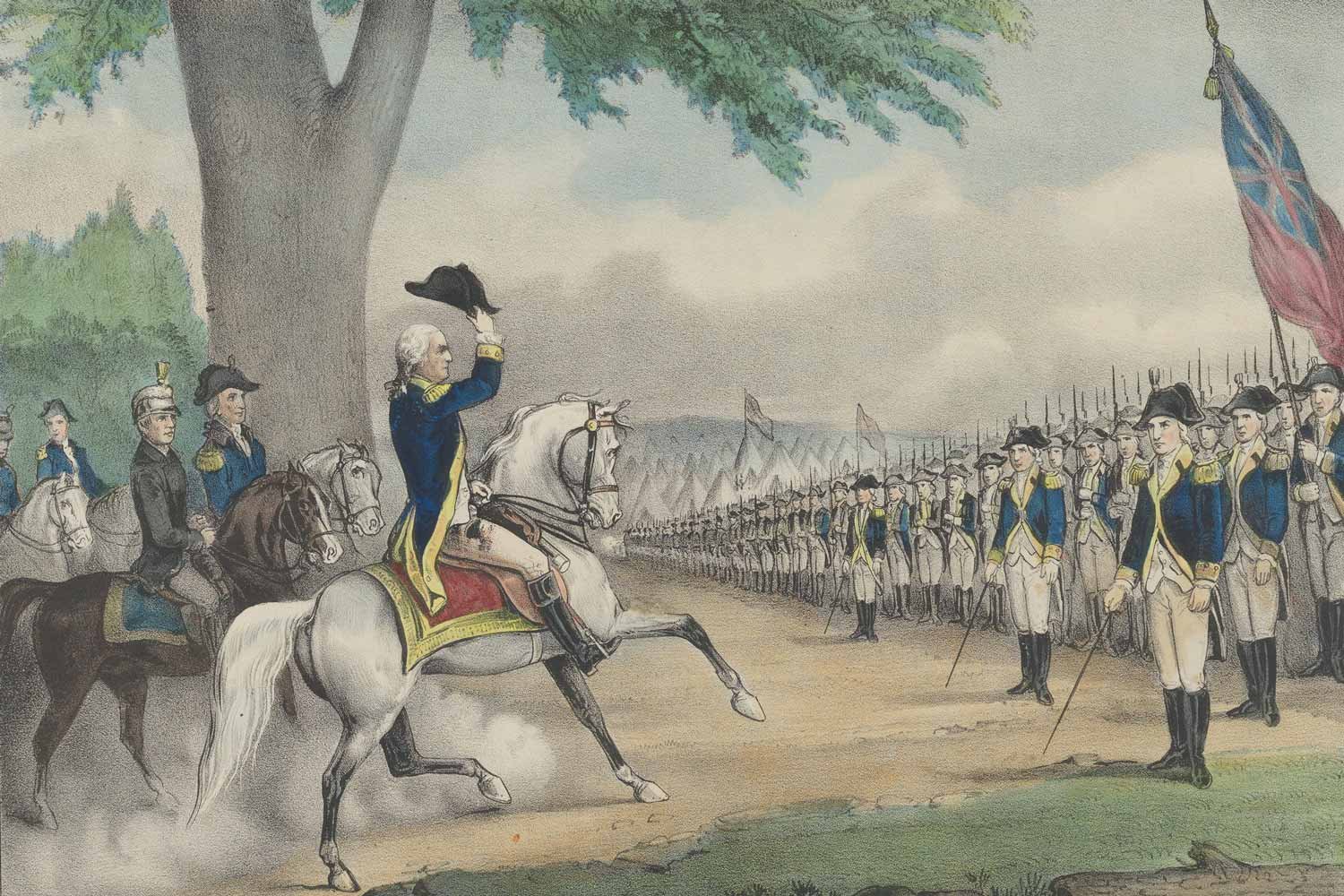

General George Washington formally took command of the Continental Army surrounding Boston on July 3, 1775. He immediately began to organize and train the troops and his natural aggressiveness was soon on display.

When it came to finding the right man to command the new Continental Army assembled around Boston, George Washington was the logical choice. John Adams quickly nominated Washington and Congress unanimously approved. As Adams stated, “This appointment will have a great effect in cementing and securing the Union of these colonies.”

As befitting a wealthy landowner in colonial Virginia, George Washington became active in the colony’s politics in the 1750s. He first ran for a seat representing Frederick County in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1755 but lost the election. Interestingly, it was the only political race he would ever lose. Washington ran for that same seat in 1758 and was victorious, and he held this seat for seven years.

Martha Washington was our nation’s first First Lady and lived in the shadow of her larger-than-life husband George. However, most Americans do not realize that she was a very capable woman and, when given the opportunity, managed her own affairs quite well.

When George Washington resigned as Colonel and Commander of the Virginia Regiment in 1758, he returned to Mount Vernon to begin his life as a gentleman planter. Although in less than twenty years Washington would be called away by his country, his time between the French and Indian War and the American Revolution was a significant portion of this great man’s life.

With the demise of Lawrence Washington in 1752, George Washington inherited much of his stepbrother’s property, becoming a significant landowner at the age of 20. Lawrence’s passing also opened up an Adjutant’s position in the Virginia militia that George coveted given his love of military history and desire to follow in his brother’s footsteps.

George Washington is more responsible for the creation of America than anyone else in our country’s incredible history. He was the right man with the right set of characteristics and talents at just the right time. It is hard to imagine the United States could have happened without his presence.

After eight years as Vice President under George Washington, John Adams hoped to succeed the Father of our Country as President of the United States. His successful election in 1796 gave him his chance.

John Adams dominated the Second Continental Congress like no other man and was tireless in his efforts to move the assembly towards independence. He sat on ninety committees and chaired twenty-five of them. No other delegate matched his workload.

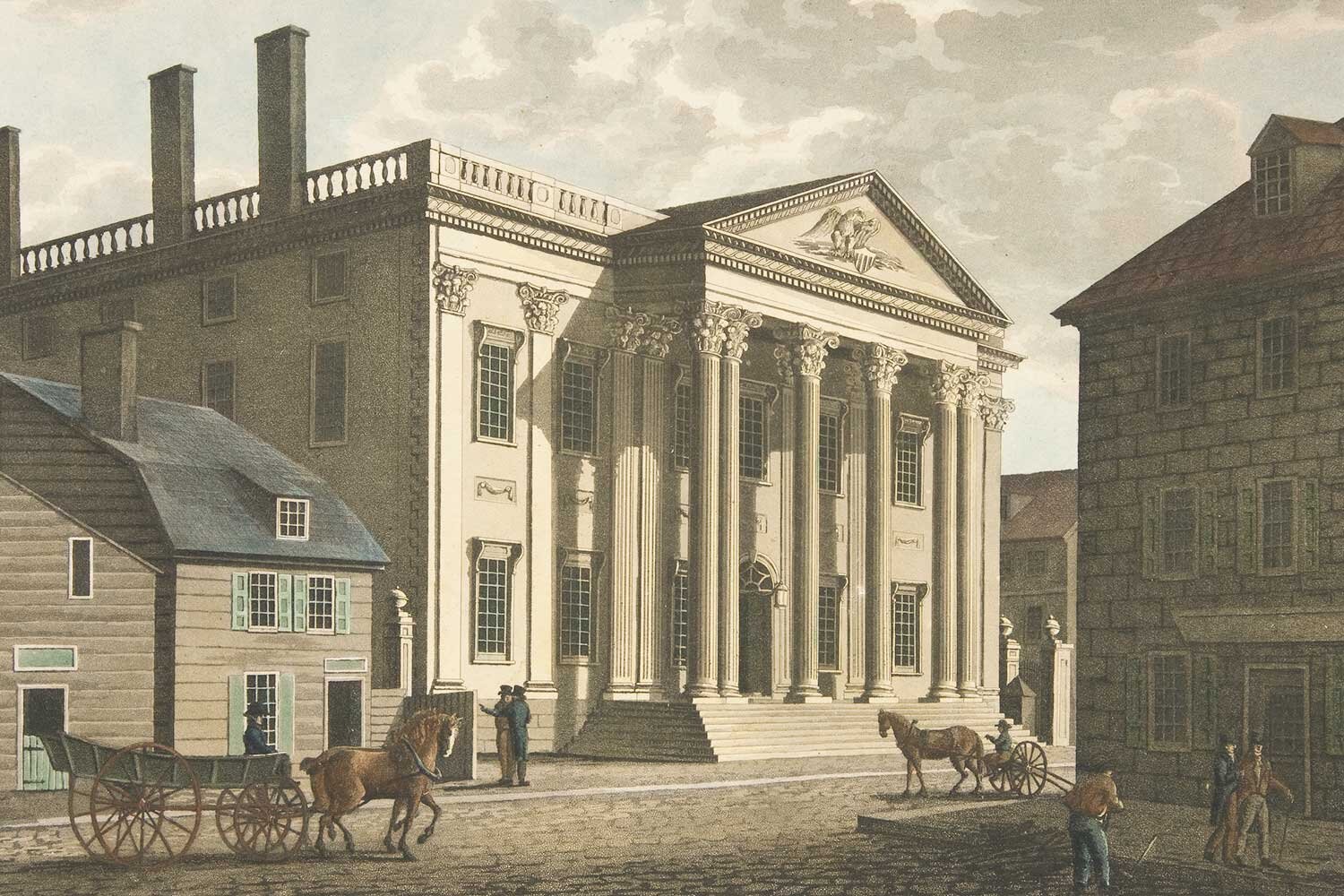

The Second Continental Congress convened in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, soon after “the shot heard round the world” was fired at the battles of Lexington and Concord. None of the delegates knew it at the time, but John Adams was to dominate the proceedings for much of the next two years.

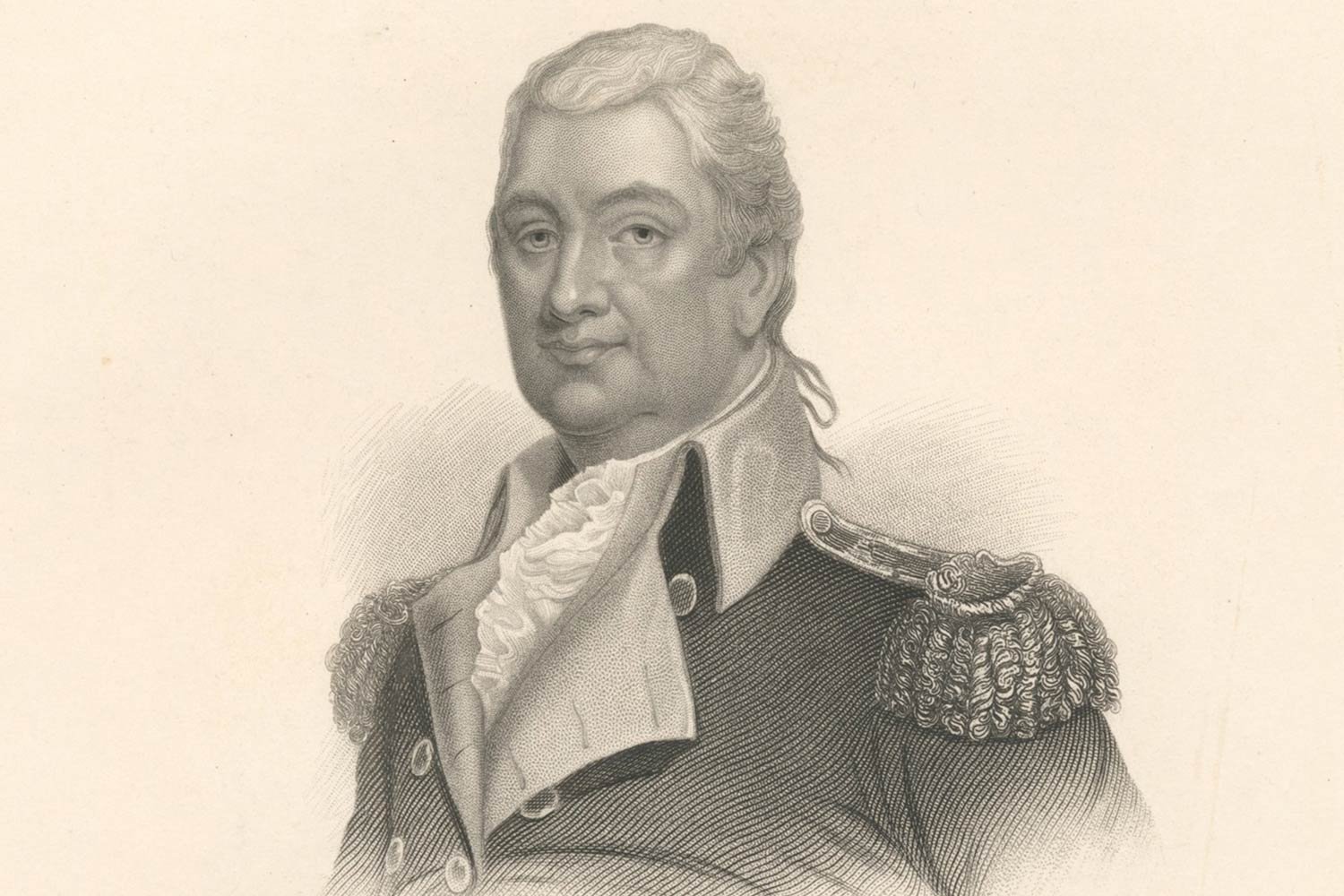

Henry Knox was 44 years old when he retired from public office after devoting the previous two decades to the American cause. Henry and his dear wife Lucy headed to Thomaston, Maine, where Henry built a three-story mansion on a large family estate which he named Montpelier.

After the American Revolution, General Henry Knox resigned his army commission and served as Secretary of War from 1785 to 1795. Knox’s ten-year span in that office is longer than other Secretary of War/Defense in our nation’s history.

In the winter of 1775-76, Colonel Henry Knox, brought fifty-nine cannons from Fort Ticonderoga to the Continental Army besieging Boston, an incredible 300-mile trek over frozen rivers and snowy mountains.

Henry Knox is arguably the least known and most under-appreciated of our nation’s early military leaders. He was involved in practically every major battle in the northern campaigns of the American Revolution, and was instrumental in the creation of the United States Army after the War.

In his Farewell Address, President Washington shared his thoughts on several topics, including our national debt and the need for our country to remain fiscally prudent.

After eight years in office, President Washington was ready to step down. He had planned to retire at the end of his first term but was talked out of it. During this second run at saying goodbye to public life, Washington was determined to finally retire.

No man has had a greater impact on the United States than George Washington. This quintessential American carried the country through eight long years of its Revolution and devoted another eight years getting the new Constitutional government established as its first President. Washington was one of those rare individuals who seemed destined, almost from birth, for greatness, as if the hand of Divine Providence was watching over and protecting him, saving him for greater things.